Topic: Real Estate

American skyscrapers face an uncertain future amid coronavirus

In boom-and-bust San Francisco, pandemic brings grim new reality

The ‘shadow banks’ are back, and still too big to fail

Open-source smartphone database offers a new tool for tracking coronavirus exposure

Researchers from Berkeley Haas and four other universities have released a trove of smartphone tracking data in an open-source database—a powerful tool for studying how people are changing their movement patterns and potential exposure levels during the coronavirus pandemic.

The Covid-19 Exposure Indices, created by Berkeley Haas Asst. Prof. Victor Couture and researchers from Yale, Princeton, the University of Chicago, and the University of Pennsylvania in collaboration with location data company PlaceIQ, is aimed at academic investigators studying the spread of the pandemic. The data sets allow researchers to visualize how people can potentially be exposed to those infected with the virus, based on cell-phone movements to and from businesses and other locations where a great deal of the exposure happens.

Couture hopes that researchers may start to find correlations between the disease and certain venues and travel patterns. Looking forward, the data also could be useful in anticipating the movement patterns that predict where future outbreaks could reemerge once restrictions are lifted. “The end goal is to identify how changes in exposure rates within different types of venues and for different demographic groups impact the number of cases,” says Couture.

Couture and his collaborators are the first academics to release open-source smartphone location data. They are part of a much bigger movement of researchers, companies, and institutions making data easily and freely available to study the pandemic. For instance, Apple, Google, Foursquare, and other big companies have also released movement data. Couture hopes that by being transparent about their data source, methodology, and potential biases, they can make available data that is suitable for peer-reviewed research.

“We’re in the midst of an unprecedented sharing of data from the academic and technical communities,” Couture says. “We hope everyone can use this data to influence better policies during the coronavirus pandemic.“

We’re in the midst of an unprecedented sharing of data from the academic and technical communities. We hope everyone can use this data to influence better policies during the coronavirus pandemic.

The smartphones in our pockets are all equipped with GPS, and depending on privacy settings, many popular applications record our geolocation. Data providers buy and aggregate location information from different applications, and build databases that record the movement and visits to various venues for millions of devices.

Couture and his colleagues have so far released two indices derived from this smartphone movement data: the location exposure index (LEX), showing our movements between states and counties, such as people flying or driving across the country; and the device exposure index (DEX), showing how many people (as measured by their devices) we are coming into close proximity with outside the home. For instance, if you drive to Walmart and 100 other phones are at that same location, and then you drive to a drugstore with 50 people with phones inside before returning home, your DEX exposure level would be 150 people. More detailed data that includes types of venues (grocery stores, drugstores, big-box stores, parks) will be released soon.

An application of the data is shown below. This animated time-lapse map from January 23 to April 2 shows how people’s movements dropped much more quickly in some areas than in others, such as in the South and Southeast of the United States. This is represented by color changes from yellow to green to dark purple as the average device exposure within a county went down.

The data can’t tell researchers how well people are practicing social distancing at any given location, and therefore their specific risk of catching the coronavirus. But it can start to reveal how successful various policies—such as states of emergencies and shelter-in-place orders—have been. “When you prescribe rules of movement, when you tighten them, and when you relax them—you can correlate that with what people are actually doing and which groups and areas are reducing their exposure,” says Couture.

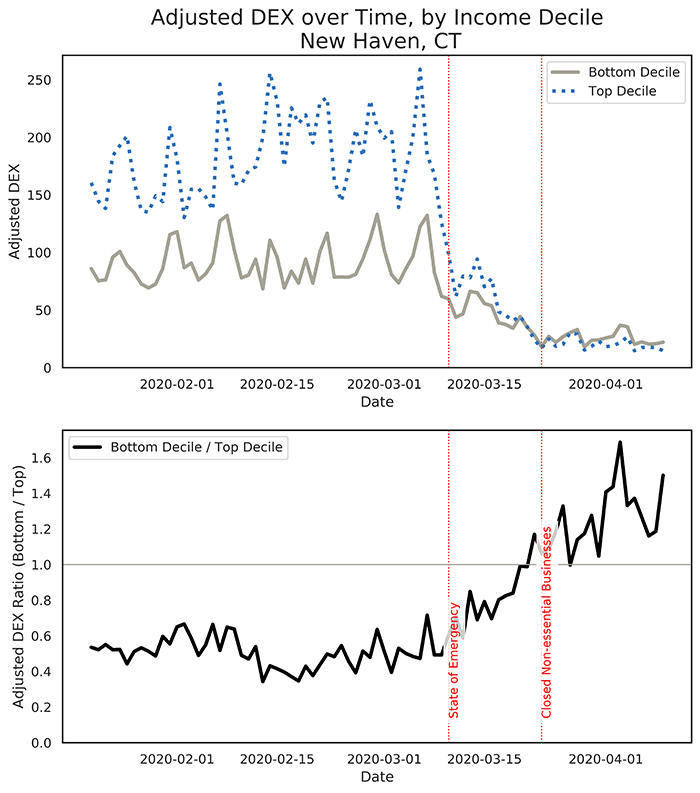

“It often looks like people start to reduce their exposure when a state of emergency is declared, but when the actual shelter in place order comes in, it has less impact on movement,” says Couture. An example is the analysis charted below for New Haven-Milford, Connecticut, which showed that the announcement of the state of emergency itself appeared to be a powerful mechanism that convinced people to reduce their movements, and hence their exposure, to the virus.

The exposure indices Couture and colleagues have compiled also include demographic information that can show which groups are at greater risk for exposure, such as minorities and low-income people. Exposure levels vary over time: The top chart in the set below shows that people living in New Haven, Connecticut neighborhoods with median incomes in the top 10% initially had higher exposure rates than those in the bottom 10%. After a state of emergency was declared, exposure levels in high-income neighborhoods declined much faster than in low-income neighborhoods. This may be because lower income people are more likely to work on the front lines in essential business, and have less ability to reduce their exposure than those who can afford to shelter at home.

The bottom panel shows the ratio of the device exposure index (DEX) for people living in neighborhoods with median income levels in the bottom 10% relative to those in the top 10%. A value higher than 1 signals that exposure is higher in low-income than in high-income neighborhoods

These patterns could prove helpful in showing which locations and demographics have the potential for greater exposure under different types of orders when policies have been gradually lifted.

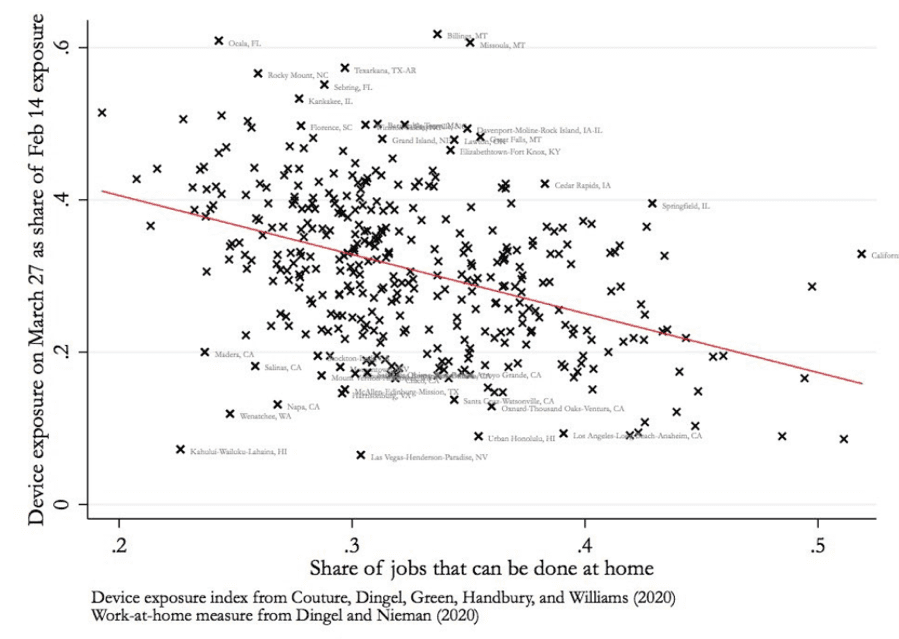

As another example, the graphic below shows that metropolitan areas with more jobs that can be done from home had larger reductions in potential exposure to the coronavirus. Again, this correlation suggests that who works from home depends on who can afford to do so while remaining gainfully employed.

Eventually, the explosion of location data has the potential to tease out even deeper stories explaining not just the hidden patterns behind our unique location in the world, but also the unexpected things that larger groups and types of places share in common. “One of the things we want to encourage is careful work to identify the causations behind these correlations,” says Couture.

The Covid-19 Exposure Indices were created by Jonathan Dingel of the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, Kevin Williams of the Yale School of Management, Jessie Handbury of the Unviersity of Pennsyania’s Wharton School of Business, Allison Green of Princeton University, and Victor Couture at Berkeley Haas.

UC Berkeley professors suggest mortgage crisis may be imminent amid coronavirus pandemic

Looming nightmare in mortgage industry, experts warn

Berkeley Haas Professors Nancy Wallace and Richard Stanton were some of the few voices to forewarn of the massive risk posed by shoddy practices in the mortgage industry prior to the 2008 financial crisis.

Unfortunately, history seems to be repeating itself.

More than two years ago, Wallace and Stanton again began raising the alarm that the mortgage landscape that emerged from the last crisis is dominated by “nonbank” lenders who operate with little of their own capital or access to emergency cash. It was another disaster waiting to happen, they warned, and called for increased oversight.

No one predicted a shock the size and speed of the coronavirus pandemic, but it’s now upon us, and Wallace fears the worst. Millions of laid-off Americans won’t be able to make mortgage payments, and have been given a temporary payment reprieve by the federal rescue package. This plummeting cash flow could quickly push fragile nonbanks into bankruptcy. And since so many of the loans they service are backed by the U.S. government, that’s who will be left holding the bag.

“The $2.2. trillion (coronavirus relief act) was the largest in history, but we’re talking about liabilities that are orders of magnitude bigger,” Wallace says. “Solutions are going to have to involve trillions of dollars. It could be the bailout of all bailouts.”

“Solutions are going to have to involve trillions of dollars. It could be the bailout of all bailouts.”

Wallace says this new crisis will begin to show itself within the next 30 days, as people forgo their monthly payments and the highly leveraged nonbanks face margin calls from the brokers they’ve borrowed from—commercial banks like JP Morgan Chase and Wells Fargo Bank and investment banks such as Morgan Stanley. They need cash to pay these lenders, and they don’t have it. The nonbanks have already begun asking for a rescue.

We asked Wallace, who has studied real estate industry financial dynamics for the past three decades, to explain this looming mortgage crisis.

What are nonbanks, and who are the biggest players?

Mortgages are originated and serviced by two types of institutions. Traditional lenders are the highly regulated banks, funded with deposits or Federal Home Loan Bank advances. They tend to have multiple lines of business. Nonbank lenders, in contrast, are lightly regulated and get their funding through short-term credit. Usually their only line of business is originating and servicing residential mortgages.

Some of the biggest players are Quicken Loans, Mr. Cooper Group, and Freedom Mortgage. They include about 1,088 smaller companies as well.

When did you become aware of the risks posed by nonbanks?

The standard narrative of the 2007-2010 housing crisis centers on the collapse of the housing bubble that was fueled by low interest rates, easy credit, low regulation, and subprime mortgages. However, we found nonbanks played an overlooked role, defaulting on their credit agreements and contributing to the collapse.

Why and how have nonbanks grown?

After the financial crisis, the traditional banks were put under heavy regulation. Because of the stringent capital requirements and the fact that they lost a lot of money servicing defaulted mortgages, most of the big banks scaled back their residential mortgage businesses. A number of large banks sold off loan servicing rights, and the nonbanks stepped in. The growing market share of the nonbanks came about in part because they were very nimble with new platform lending technology—like Quicken, with the eight-minute mortgage.

Nonbanks originated 20% of single-family home loans in 2007, and that had grown to half of loans by 2016. Today they service about two-thirds of home loans. The bigger problem is they tend to have a high proportion of the riskier loans to low- and moderate-income people, which are backed by the U.S. government. We’re talking trillions of dollars. As of February 2020 they originated 88% of the loans sold to Ginnie Mae, which is part of the Department of Housing and Urban Development and has a $2.1 trillion portfolio. And 61% of loans sold to the GSEs (government sponsored enterprises) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which have a combined residential single family loan portfolio of about $4.9 trillion.

The bigger problem is they tend to have a high proportion of the riskier loans to low- and moderate-income people, which are backed by the U.S. government. We’re talking trillions of dollars.

How do nonbanks get their money, and how big is their debt exposure?

They rely on short-term lending known as warehouse lines of credit. These credit lines are usually provided by larger commercial and investment banks. It’s difficult to get data because most nonbank lenders are private companies which are not required to disclose their financial structures. That was the subject of our Brookings paper, which was the first public tabulation of the scale of warehouse lending to nonbanks. We found there was a $34 billion commitment on warehouse loans at the end of 2016, up from $17 billion at the end of 2013. That translated to about $1 trillion in short-term “warehouse loans” funded over the course of one year. As of year end 2019, there was $101 billion of warehouse commitments on the books of warehouse lenders.

Last year was a banner year. Nonbanks originated nearly a trillion dollars of mortgages that were securitized by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae—the largest origination volume since 2006. However, the high levels of refinancing due to historically low interest rates had a significant negative impact on the value of the mortgage servicing rights held by nonbanks.

If nonbanks are so big and borrow so much money, why aren’t they regulated like banks?

The simple answer is they have a very powerful lobby, the Mortgage Bankers Association. What the industry leaned on was that they were saving the mortgage market because the banks didn’t want to hold mortgages anymore. Nonbanks were happy to promise that they would service 30-year loans and pay the bondholders, whether or not they received borrower principal and interest payments, but there are no mechanisms in place to hold them to that promise. They were gambling that the market wouldn’t crash.

What the industry leaned on was that they were saving the mortgage market because the banks didn’t want to hold mortgages anymore.

The nonbanks have actively resisted paying for any form of liquidity insurance or supporting any credible oversight similar to banks. Their regulator, the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (CSBS), does not have high-quality loan-level data for the mortgage industry. That’s why they recently asked our team—Paulo Issler, Christopher Lako, Richard Stanton and me, here at the Real Estate and Financial Markets Lab in the Fisher Center for Real Estate and Urban Economics—to perform detailed data breakdowns and analysis for them. They do not have the data to perform this analysis themselves.

Did anything change after your 2018 paper, co-written with Federal Reserve economists, which called for greater oversight?

Ginnie Mae started trying to require higher capital and liquidity thresholds as well as stress tests, requiring them to show how they would handle an economic shock. They had an initiative called Ginnie Mae 2020, but they were getting major pushback from the industry. In addition, the Conference of State Bank Supervisors has been trying hard to standardize the reporting rules, but they have no data, and they have little power.

Under the $2.2 trillion emergency CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security), mortgage servicers are required to allow borrowers to delay payments for as long as a year. What do you expect will happen now?

I think the situation is extremely serious, a looming nightmare. We’ve had 16 million people file for unemployment in three weeks. We know that most Americans can’t even withstand a $400 shock to their finances. Millions of people won’t be able to make their mortgage payments. They’ve been told to call their lenders and tell them they can’t pay, and the phones are ringing off the hook.

I think the situation is extremely serious, a looming nightmare.

The immediate problem for the nonbanks is the risk to their warehouse lines of credit, and the fact that the nonbank loan servicers still have to make payments to the mortgage-backed security bondholders, even if people don’t pay their mortgages. Margin calls have been in the level of tens of millions of dollars and the creditors are demanding cash. Not making your margin calls on lines of credit is a serious problem and could trigger default. Nonbanks are also facing millions of dollars of margin exposure from short sales of mortgage-backed securities. These onerous margin calls, some as large as $100 million for a single institution, are what’s leading their lobbyists, the Mortgage Banking Association, to go to the Securities and Exchange Commission and demand that the brokers be forbidden from exercising their margin rights. It’s ridiculous, because the brokers—big banks like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley—have every right to play hardball. The SEC has turned down the request.

Why does this pose such a threat to the U.S. government, and ultimately, to taxpayers?

Most of these loans are guaranteed by the U.S. government through Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac. The nonbank lenders have been given some forbearance, and will eventually receive compensation for the payment shortfalls they are experiencing, but they have a timing problem. In the meantime they still have to make timely payments of interest and principal—for 120 days to the Fannie and Freddie MBS bondholders, and, in the case of those who owe to Ginnie Mae mortgage-backed security bondholders, until they go bankrupt. I’m not sure some of them have the liquidity to last even 30 days, and many won’t be able to do it for three months, much less a year. We are going to see bankruptcies, and substantial loss in lending capacity as we did in 2007, when we lost two-thirds of lending capacity. This might be worse because unemployment may be worse.

They can’t keep pushing the envelope and then expect to be rescued. They don’t want to follow any of the rules that banks follow, and then they want to be treated like banks when liquidity shocks occur. It’s just wrong.

Will any of the stimulus measures passed so far help?

The nonbanks are already asking for a bailout, but none of the federal relief efforts so far have included them. The MBA tried to get some protection in the CARES Act, which had $450 billion in loans and loan guarantees from the Fed and Treasury. But they were excluded for a reason—because these firms have pushed every boundary and rejected every form of oversight. Thus far, they have also been excluded from the actions the Fed has been taking, including a new round of quantitative easing, and participation in the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility, which is a way to provide liquidity. Ginnie Mae has now created an assistance program to provide loans to its nonbank counterparties who are unable to cover the principal and interest payments to bondholders. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have refused to provide such assistance to their nonbank counterparties, because they are still under conservatorship status from the 2008 crisis and face their own capital shortfalls.

So some kind of bailout is nearly inevitable?

To save the market, the nonbanks will have to be bailed out either by the Fed or by the U.S. Treasury. This will be very difficult under restrictions put in place concerning nonbank bailouts under the Dodd-Frank Act. The cost is going to be very high. In my opinion, there has to be a quid pro quo from the industry in the form of significant future fees in return for such extraordinary support—they can’t keep pushing the envelope and then expect to be rescued. They don’t want to follow any of the rules that banks follow, and then they want to be treated like banks when liquidity shocks occur. It’s just wrong.

Mortgage industry seeks billions in federal help as homeowners stop paying their loans

Coronavirus rent crisis: ‘Millions of Americans will have trouble paying rent this month’

Expert guide: Coronavirus impacts on business, the economy, and leadership

Berkeley Haas has a wide range of experts who can talk about how the coronavirus is impacting businesses and the economy, putting leaders to the test, and changing workplaces.

Need help finding the right expert? Contact our media relations team.

Economic Impact

David Levine

David Levine

Professor | Chair, Haas Economic Analysis and Policy Group

[email protected]

(925) 899-5938

Topics: Management practices in large corporations and multinationals, procedures and norms around behavior change and hygiene programs, impacts of high and low wages and of education in the business sector, labor economics, macroeconomics.

Laura D. Tyson

Distinguished Professor of the Graduate School | Faculty Director, Institute for Business & Social Impact

[email protected]

Assistant: Cynthia Okita [email protected]

Topics: Economic impact on global, U.S. and California economies; trade and competitiveness; jobs and disruption

James A. Wilcox

James A. Wilcox

Professor of Economic Analysis and Policy and Finance

[email protected]

(510) 642-2455

Topics: Macroeconomics and markets, recessions, Federal Reserve policy, business conditions, banking, consumer spending, unemployment and inflation

Severin Borenstein

Severin Borenstein

Professor, Economic Analysis and Policy | Faculty Director, Energy Institute at Haas

[email protected]

(510) 642-3689

Topics: Oil prices, energy markets, airline industry

Enrico Moretti

Enrico Moretti

Professor, Real Estate

[email protected]

510 642-6649

Topics: Urban economics, labor economics, economics of cities and regions, real estate

Kevin Coldiron

Kevin Coldiron

Lecturer, Finance

Topics: Stock market, finance

Jerome Dodson

Lecturer, Responsible Business

Topics: Stock market

Management, Leadership, Culture, Communication & Psychology

Jennifer Chatman

Jennifer Chatman

Professor of Management, Management of Organizations Group

[email protected]

(510) 642-4723

Topics: Organizational culture, crisis leadership, coronavirus impact on work and productivity, general management

Ellen Evers

Ellen Evers

Assistant Professor, Marketing

Topics: Influence of fear and other emotions on behavior, risk perceptions, risk communication, judgement and decision making

Don Moore

Don Moore

Professor, Management of Organizations

[email protected]

(510) 642-1059

Topics: Confidence and overconfidence regarding the course of the pandemic; remote work and productivity in self-quarantine; crisis leadership; managing people at a distance

Juliana Schroeder

Juliana Schroeder

Assistant Professor, Management of Organizations

[email protected]

510-664-9692

Topics: Differences between online and offline communication, judgment and decision making, interpersonal and intergroup processes

Dana Carney

Dana Carney

Associate Professor; Director, Institute for Personality and Social Research

Topics: Cultural impact of social distancing

Professor Emeritus, Management of Organizations and UC Berkeley Center for Catastrophic Risk Management

[email protected]

(510) 642-5221

Topics: Managing crises, highly reliable organizations, organizational resilience

Kurt Beyer

Kurt Beyer

Senior Lecturer, Entrepreneurship

[email protected]

(415) 412-9551

Topics: Innovation during recessions, strategy, entrepreneurship, intrapreneurship in large organizations

Alex Budak

Alex Budak

Lecturer, Management of Organizations

Topics: Leadership, management, and adapting to/thriving during change and uncertainty

Peter Wilton

Peter Wilton

Senior Lecturer, Marketing

[email protected]

(415) 425-5151

Topics: Leadership and general management; impacts on innovation and customer loyalty in turbulent times

Workplace Impacts & Remote Work

Clark Kellogg

Clark Kellogg

Lecturer in Creativity, Design, and Innovation

[email protected]

(510) 388-2967

Topics: Working remotely, resilient responses and creative problem solving in the midst of chaos

Molly Turner

Molly Turner

Lecturer, Business & Public Policy

Topics: Impact of telecommuting on urban development, urban innovation, technology and cities, economic development and tourism policy

Sahar Yousef

Sahar Yousef

Lecturer

Topics: How to maintain productivity, effectiveness, and motivation across teams while people are working from home, cognitive neuroscience

Marissa Saretsky

Marissa Saretsky

Lecturer, Responsible Business

Topics: Responsible steps that business must take to protect employees, suppliers, and customers; how can businesses take a leadership role in the crisis

Rebecca Portnoy

Rebecca Portnoy

Lecturer, Management of Organizations

[email protected]

(206) 890 8374

Topics: Leadership, remote work, virtual meetings, creating engaging experiences

Supply chains

Olaf Groth

Lecturer, Business & Public Policy

[email protected]

(415) 205-0807

Topics: Global tech supply chain security; AI & IOT; data markets; privacy & surveillance computing; future of work; business & policy; tech ethics & governance.

Industries

Adam Leipzig

Adam Leipzig

Lecturer, Persuasive Communication & Interpersonal Dynamics

[email protected]

(323) 791-0255

Topics: Impact on the film, entertainment, media, content creation and creative industries

Real estate & economics forecast: a recession is on the horizon

Unemployment is at its lowest rate in 50 years, there are almost 7 million job openings nationwide, and consumer confidence is at its highest level in a decade. There’s more venture capital flowing than at any point since 2000, and commercial real estate loan origination is at its highest point ever. So, what could go wrong?

Lots, said Kenneth Rosen, faculty director for the Haas School’s Fisher Center for Real Estate & Urban Economics, who foresees a recession within the next 18 to 24 months.

“We’ve had a sugar high for the economy, and it will wear off,” said Rosen, delivering his annual forecast at the 41st Annual Real Estate & Economics Symposium in San Francisco this week. “We’re in the last stages of a very good recovery, but we’re buying this time by spending a lot of money that we don’t have.”

Even so, Rosen does not foresee a crash in the real estate market anything like 2004 to 2007 or the late 1980s, and there’s still plenty of “dry powder”—or cash available for investment, he said. While real estate is overvalued compared to historical prices, it’s not overvalued compared to everything else, he said.

“This is not a very dramatic forecast, but the risks have risen dramatically and this is just the beginning of volatility,” he said. “There will be correction, and the Bay Area is likely to have a bigger correction than the rest of the country, because we’ve gone up so much.”

“A sledgehammer to break open a walnut”

Rosen pointed to rising interest rates, a ballooning national deficit, increasingly restrictive immigration policies in a tight labor market, and the escalating trade war with China as trouble signs. With $250 billion in tariffs imposed and $257 billion more threatened by President Trump, Chinese retaliation is to be expected.

“We certainly have problems with China, but tariffs are an exceptionally a blunt tool. It’s like using a sledgehammer to break open a walnut,” said Rosen, who is also chairman Rosen Consulting Group, a real estate market research firm. “No one wins in a trade war.”

The combined economic stimulus of tax cuts and increased spending has overheated the economy, and left few tools in policy makers’ arsenal to recover from the next recession, he said. A gridlocked Congress would not be able to pass a spending increase bill, or another tax cut. “In a full employment economy, the deficit should be zero or positive, so we should be at a balanced budget today. We’re doing the opposite. We’re not going to be ready for the next big downturn.”

While he had plenty of critiques of President Trump and his administration, he said Congress is also at fault. “There are no fiscal hawks any more. There’s no one who believes in balanced budgets.”

Red-hot economy

In the immediate future, however, the economy remains red hot. There’s a boom in job creation nationwide, especially throughout the West. California as a whole is a bit lower than the rest of the region, but it still had 1.9 percent growth in job creation year-over-year. Unemployment in San Francisco hovers just over 2 percent.

“The tech cities are going strong: Seattle, Austin, Silicon Valley, Denver, San Francisco, and Oakland are still very strong. The only thing constraining these places is the fact that housing is so expensive that they can’t get people to come. We’d be growing faster if we can solve some of those issues.”

Real estate forecast

Nationwide, retail is still struggling while industrial properties are hot, with vacancy rates at their lowest point since the 80s. “It’s a red-hot sector because of e-commerce, which is driving the demand for this space and bypassing retail network.”

In terms of commercial real estate, Rosen predicts cap rates—or the rates of return on commercial property—are expected to rise after historic lows. He warned the crowd of 300 real estate and finance professionals in the room to not be too smug. “We’ve had big periods of appreciation in the last decade because cap rates went down. Don’t think it’s because you’re smart—it’s because they repressed interest rates. It’s going to reverse. We’ll have headwinds.”

His advice? “As a lender, I’d say now’s the time to be cautious. Don’t lend to inexperienced people. You’ve got to be able to hold through the next six years—don’t think you’re going to miss this recession,” he said. “As an investor, it’s now is the time harvest or hedge, don’t wait for the next cycle.”

Nationally there’s strong demand for office space, but it’s nothing like previous booms. And vacancy rates have stopped going down because businesses need less space per worker—thanks to open floor plans and co-working spaces.

“The WeWorks of the world are 50 percent more dense than traditional office spaces,” he said.

Although the rental market peaked several years ago and home ownership is creeping back up, rental vacancy rates are low. The proportion of young adults living with their parents has begun to drop from a high of 32 percent in 2016. In the Bay Area, apartment vacancy rates are below 4 percent, and rents are rising again after appearing to top out.

California—a victim of its own success?

California homes have become increasingly unaffordable–just 30 percent of people can afford a median priced home, compared with 50 percent nationally. In the Bay Area, prices were up almost 10 percent year-over-year in September. Recently, however, there are signs that home prices may be beginning to drop—whether it’s due to rising interest rates or people leaving the region.

All this leads Rosen to believe California may soon be a victim of its own success.

“We may be the cause of our own demise. With high housing prices and congestion, people are going to move elsewhere,” he said. “You’ve seen reports that up to a third of people are thinking of relocating in the next five years. Add to that the higher taxes that we keep on voting on ourselves, and I think we could be in a situation where we’ve hit our peak moment and it’s just a question of how fast we can slow down.”

Minority homebuyers face widespread statistical lending discrimination, study finds

Face-to-face meetings between mortgage officers and homebuyers have been rapidly replaced by online applications and algorithms, but lending discrimination hasn’t gone away.

A new University of California, Berkeley study has found that both online and face-to-face lenders charge higher interest rates to African American and Latino borrowers, earning 11 to 17 percent higher profits on such loans. All told, those homebuyers pay up to half a billion dollars more in interest every year than white borrowers with comparable credit scores do, researchers found.

The findings raise legal questions about the rise of statistical discrimination in the fintech era, and point to potentially widespread violations of U.S. fair lending laws, the researchers say. While lending discrimination has historically been caused by human prejudice, pricing disparities are increasingly the result of algorithms that use machine learning to target applicants who might shop around less with higher-priced loans.

“The mode of lending discrimination has shifted from human bias to algorithmic bias,” said study co-author Adair Morse, a finance professor at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. “Even if the people writing the algorithms intend to create a fair system, their programming is having a disparate impact on minority borrowers—in other words, discriminating under the law.”

First-ever dataset

A key challenge in studying lending discrimination has been that the only large data source that includes race and ethnicity is the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HDMA), which covers 90 percent of residential mortgages but lacks information on loan structure and property type. Using machine learning techniques, researchers merged HDMA data with three other large datasets—ATTOM, McDash, and Equifax—connecting, for the first time ever, details on interest rates, loan terms and performance, property location, and borrower’s credit with race and ethnicity.

The researchers—including professors Nancy Wallace and Richard Stanton of the Haas School of Business and Prof. Robert Bartlett of Berkeley Law—focused on 30-year, fixed-rate, single-family residential loans issued from 2008 to 2015 and guaranteed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

This ensured that all the loans in the pool were backed by the U.S. government and followed the same rigorous pricing process—based only on a grid of loan-to-value and credit scores—put in place after the financial crisis. Because the private lenders are protected from default by the government guarantee, any additional variations in loan pricing would be due to the lenders’ competitive decisions. The researchers could thus isolate pricing differences that correlate with race and ethnicity apart from credit risk.

The analysis found significant discrimination by both face-to-face and algorithmic lenders:

- Black and Latino borrowers pay 5.6 to 8.6 basis points higher interest on purchase loans than White and Asian ethnicity borrowers do, and 3 basis points more on refinance loans.

- For borrowers, these disparities cost them $250M to $500M annually.

- For lenders, this amounts to 11 percent to 17 percent higher profits on purchase loans to minorities, based on the industry average 50-basis-point profit on loan issuance.

“Algorithmic strategic pricing”

Morse said the results are consistent with lenders using big data variables and machine learning to infer the extent of competition for customers and price loans accordingly. This pricing might be based on geography—such as targeting areas with fewer financial services—or on characteristics of applicants. If an AI can figure out which applicants might do less comparison shopping and accept higher-priced offerings, the lender has created what Morse calls “algorithmic strategic pricing.”

“There are a number of reasons that ethnic minority groups may shop around less—it could be because they live in financial deserts with less access to a range of products and more monopoly pricing, or it could be that the financial system creates an unfriendly atmosphere for some borrowers,” Morse said. “The lenders may not be specifically targeting minorities in their pricing schemes, but by profiling non-shopping applicants they end up targeting them.”

This is the type of price discrimination that U.S. fair lending laws are designed to prohibit, Bartlett notes. Several U.S. courts have held that loan pricing differences that vary by race or ethnicity can only be legally justified if they are based on borrowers’ creditworthiness. “The novelty of our empirical design is that we can rule out the possibility that these pricing differences are due to differences in credit risk among borrowers,” he said.

Overall decline in lending discrimination

The data did reveal some good news: Lending discrimination overall has been on a steady decline, suggesting that the rise of new fintech platforms and simpler online application processes for traditional lenders has boosted competition and made it easier for people to comparison shop—which bodes well for underserved homebuyers.

The researchers also found that fintech lenders did not discriminate on accepting minority applicants. Traditional face-to-face lenders, however, were still 5 percent more likely to reject them.

CONTACTS & RESOURCES

Berkeley Haas Media Relations: Laura Counts, [email protected], (510) 643-9977

Berkeley Law: Prof. Robert Bartlett, [email protected]

Meet the faculty: Haas welcomes three rising academic stars

Three new assistant professors have joined the Berkeley Haas faculty, with research interests that range from how financial news influences markets to the unintended consequences of mortgage market regulations to developing more accurate ways to predict consumer behavior.

Anastassia Fedyk and Matteo Benetton will join the Finance Group, while Giovanni Compiani will be part of the Marketing Group.

“We’re thrilled to have these three rising stars join us this year,” said Prof. Candace Yano, associate dean for academic affairs and chair of the faculty.

The three new faculty members have already won awards for their research and have published in top journals. As is customary, they will spend the fall semester working on their research and plan to begin teaching in the spring semester.

Assistant Professor Anastassia Fedyk, Finance

For Anastassia Fedyk, coming to Haas is a homecoming of sorts. Though she was born in Ukraine and moved to the United States at age 10, she spent her high school years in Berkeley while her mother earned her PhD in accounting at Haas.

“I really loved living here back in high school, so it was always a dream to move back,” says Fedyk. “And the fact that there are so many people here working in behavioral economics makes it a perfect fit with my work.”

Knowing early on that she wanted to become a research economist, Fedyk majored in math at Princeton and did a two-year stint doing research at Goldman Sachs before heading to Harvard University to earn her PhD in business economics.

Her work spans finance and behavioral economics, and she has pursued three main research threads so far. The first focuses on financial news and how it translates into prices and trading volume in the markets. She’s looked at trading around news events and how the news is presented. “For example, if the news is printed on the front page that will prompt a much faster price response than if it’s less prominent,” she said. Or, when two old news stories are reprinted together, they are perceived as a new piece of information.

Her second line of research centers on present bias and procrastination. She’s found that although people fail to recognize these tendencies in themselves—and really do believe they’ll follow through on their plans for a new gym routine or diet—they easily recognize them in others.

Fedyk’s third line of inquiry looks at how employees’ skills relate to companies’ performance, working with a large dataset of resumes from a startup that collects public profiles. She has found that companies with an unusually high focus on sales-oriented skills tend to outperform, while companies that are heavy on administrative and bureaucratic personnel tend to do worse.

She will be teaching core finance in the evening & weekend MBA program.

Assistant Professor Matteo Benetton, Finance

Matteo Benetton also feels a kinship with Berkeley, although he had only spent three days here interviewing before moving 5,500 miles this month from the U.K, where he completed his PhD at the London School of Economics.

“The vast majority of Italian economists study at Bocconi, which is a private university, but I went to the University of Pisa’s Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies, which is public,” said Benetton, who originally hails from Treviso near Venice. “I love the idea of a high-quality public university, and the research mindset that goes with that. That’s something I value a lot. Plus, after six years in London I’m looking forward to some sunshine.”

Benetton, whose work centers on the intersection between competition in the lending market, mortgage product design, and regulation, says he was excited to find so many faculty at Haas who share his interests, both in the Finance and Real Estate groups.

Benetton’s research has shown that some banking regulations put in place after the global financial crisis have had unintended consequences, giving more advantages to big banks over smaller banks. “The regulation can actually distort competition, and increase market concentration,” he said. In one paper, Benetton recommended that regulations apply evenly to big banks and smaller lenders, to prevent established banks from gaining additional advantages.

He has also researched how innovative mortgage product design can benefit consumers and prevent the buildup of risk in the housing market. He’s looked at shared-equity mortgages, in which a government or bank lender provides a homebuyer with part of the down payment but takes some of the equity. These profit-sharing contracts can reduce risk, but homebuyers who expect prices to go up tend to avoid the since they don’t want to share the gains.

While much of his work has been focused on Europe, with his new proximity to Silicon Valley Benetton says he’s interested in exploring how fintech is changing banking and payment systems, as well as branching out into household finance.

Benetton will be finishing up a research project this fall and will begin teaching finance in the undergraduate program in January.

Assistant Professor Giovanni Compiani, Marketing

Giovanni Compiani is also a native of Italy, who comes to Haas via Yale University, where he earned a PhD in economics. He’s looking forward to opportunities for working across disciplines at Berkeley, and also to the proximity to Silicon Valley and its trove of consumer data.

“Being at a business school and at Berkeley in particular, there’s a more question-oriented approach—rather than a focus on methods it’s about ‘What real-world question do we want to address?’”, Compiani said. “At Yale, I acquired a rich set of econometrics and structural methods tools which I now look forward to applying. There are so many relevant topics in the digital economy, and at Berkeley an economist can work with a computer scientist and say something very meaningful and interesting.”

Compiani grew up in Bologna before studying economics at Italy’s prestigious Bocconi University in Milan. He completed part of his master’s at Yale and returned for his doctorate.

He has focused much of his research so far on consumer behavior, building a model that gives more flexibility than established models allow for in predicting consumer reactions to price changes. “Let’s say a tax is levied on a supermarket. The market could lower the price of products to keep the final price to consumers unchanged, or they could pass on the full increase to consumers. The best strategy depends on knowing how consumers react,” he said. “This model relaxes certain strict assumptions typically made for ease of programming, and thus delivers more robust results.”

Compiani is also investigating patterns of how consumers search across different product characteristics, such as price. “Understanding these patterns has implications both for policy and for firm strategy,” he said.

With the possibility of increased access to data sources from Silicon Valley companies, Compiani is interested in exploring new lines of research on how concerns about data privacy influence consumer behavior.

He will begin teaching marketing analytics in the undergraduate program in the spring.

A decade after housing bust, mortgage industry is on shaky ground, experts warn

Despite tough banking rules put in place after last decade’s housing crash, the mortgage market again faces the risk of a meltdown that could endanger the U.S. economy, warn two Berkeley Haas professors in a paper co-authored by Federal Reserve economists. The threat reflects a boom in nonbank mortgage companies, a category of independent lenders that are more lightly regulated and more financially fragile than banks—and which now originate half of all US home mortgages.

“If these firms go out of business, the mortgage market shuts down, and that has dire Implications for the overall health of the economy,” says Richard Stanton, professor of finance and Kingsford Capital Management Chair in Business at Haas. Stanton authored the Brookings paper, “Liquidity Crises in the Mortgage Market,” with Nancy Wallace, the Lisle and Roslyn Payne Chair in Real Estate Capital Markets and chair of the Haas Real Estate Group. You Suk Kim, Steven M. Laufer, and Karen Pence of the Federal Reserve Board were coauthors.

Bank regulation fueled boom in nonbank lenders

During the housing bust, nonbank lenders failed in droves as home prices fell and borrowers stopped making payments, fueling a wider financial crisis. Yet when banks dramatically cut back home loans after the crisis, it was nonbank mortgage companies that stepped into the breach. Now, nonbanks are a larger force in residential lending than ever. In 2016, they accounted for half of all mortgages, up from 20 percent in 2007, the Brookings Institution paper notes. Their share of mortgages with explicit government backing is even higher: nonbanks originate about 75 percent of loans guaranteed by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) or the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

Nonbank lenders are regulated by a patchwork of state and federal agencies that lack the resources to watch over them adequately, so risk can easily build up without a check. While the Federal Reserve lends money to banks in a pinch, it does not do the same for independent mortgage companies.

Scant access to cash

In stark contrast with banks, independent mortgage companies have little capital of their own and scant access to cash in an emergency. They have come to rely on a type of short-term funding known as warehouse lines of credit, usually provided by larger commercial and investments banks. It’s a murky area since most nonbank lenders are private companies which are not required to disclose their financial structures, so Stanton and Wallace’s paper provides the first public tabulation of the scale of this warehouse lending. They calculated that there was a $34 billion commitment on warehouse loans at the end of 2016, up from $17 billion at the end of 2013. That translates to about $1 trillion in short-term “warehouse loans” funded over the course of a year.

If rising interest rates were to choke off the mortgage refinance market, if an economic slowdown prompted more homeowners to default, or if the banks that extend credit to mortgage lenders cut them off, many of these companies would find themselves in trouble with no way out. “There is great fragility. These lenders could disappear from the map,” Stanton notes.

Risk to taxpayers

The ripple effects of a market collapse would be severe, and taxpayers would potentially be on the hook for losses posted by failed mortgage companies. In addition to loans backed by the FHA or VA, the government is exposed through Ginnie Mae, the federal agency that provides payment guarantees when mortgages are pooled and sold as securities to investors. The mortgage companies are supposed to bear the losses if these securitized loans go bad. But if those companies go under, the government “will probably bear the majority of the increased credit and operational losses,” the paper concludes. Ginnie Mae is especially vulnerable because almost 60 percent of the dollar volume of the mortgages it guarantees comes from nonbank lenders.

Vulnerable communities would be hit hardest. In 2016, nonbank lenders made 64 percent of the home loans extended to black and Latino borrowers, and 58 percent of the mortgages to homeowners living in low- or moderate-income tracts, the paper reports.

The authors emphasize that they hope their paper raises awareness of the risks posed by the growth of the nonbank sector. Most of the policy discussion on preventing another housing crash has focused on supervision of banks and other deposit-taking institutions. “Less thought is being given, in the housing finance reform discussions and elsewhere, to the question of whether it is wise to concentrate so much risk in a sector with such little capacity to bear it,” the paper concludes.

Stanton adds, “We want to make the nonbank side part of the debate.”

Elisse Douglass, MBA 16

VP of Development, Signature Development Group & Co-Founder, Oakland Black Business Fund

Elisse Douglass thinks a lot about the relationship between opportunity and place. As the VP of development for Signature Development Group, she manages large-scale commercial and retail developments in downtown Oakland with the aim of enlivening the community via economic activity.

When vandals disrupted Black Lives Matter protests and destroyed small businesses in downtown Oakland, she knew the Black-owned businesses would have a hard time recovering. So Douglass, who has little fundraising experience, mobilized. She launched the Oakland Black Business Damage Fund on GoFundMe, initially seeking $5,000. She raised more than 10 times that amount in a few days, eventually topping $115,000.

One of her favorite parts of the experience was the positive public reaction. “I love that because it shows that we didn’t have to explain why Black businesses matter,” Douglass says.

Inspired, she co-founded the Oakland Black Business Fund. The investment platform aims to raise $10 million to keep Black Oakland businesses open and $1 billion in investment funds for Black entrepreneurs nationally.

“If we really want to invest in this idea that Black businesses are the infrastructure for our community, economic activity, and empowerment, then we need to talk about their access to venture capital and their relationship to real estate as well,” says Douglass. “Give people opportunities [while] letting their business models adapt and compete for the future.”

Some things are fixable Douglass says. “The harder work is racism and racist systems. I think Black businesses play a really important role in the infrastructure for breaking those systems down. So we need to invest in them.”

MBA team wins first place at National Real Estate Challenge

MBA team wins first place in National Real Estate Challenge held at the University of Texas at Austin on Nov. 21. From left to right: David Eisenman, Maribel Garcia Ochoa, Jon Lam, Abby Franklin, Lecturer Bill Falik, Matt Tortorello, Andrew Sublett and Eric Valchuis.

Haas took first place in the 17th annual National Real Estate Challenge for the second year in a row, taking home a $10,000 prize. Teams from the nation’s top-ranked business schools competed at the University of Texas at Austin on Nov. 21.

The Team: David Eisenman, MBA 20, Andrew Sublett, MBA 20, Matt Tortorello, MBA 20, Eric Valchuis, MCP 20 (city planning), Maribel Garcia Ochoa, JD 21, and Jon Lam, MBA 21 & MRED+D 20 (real estate development and design).

The Field: Finalists included Haas, Georgetown’s McDonough School of Business, University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, and UPenn’s Wharton School.

The Challenge: Playing the role of a real estate investment firm, the Haas team had to decide if it should buy 1,000 mixed-income housing units in Lakewood, a fictional city modeled after New York. The firm would receive a tax abatement from the city if it converted a portion of the units into affordable housing.

The Team’s plan: The team weighed the pros and cons of investing in a housing portfolio that included market-rate and affordable housing units. After careful consideration, the team decided to invest in the Lakewood property.

The Haas Factor: The Haas team received coaching from Professor Nancy Wallace, Lecturer Bill Falik, Abigail Franklin, an investment banking and real estate student advisor, and Haas alumni.“Questioning the status quo and having confidence without attitude set us apart from the pack,” said Eric Valchuis, MCP 20. “We prepared for this challenge for months and delivered a story-centered presentation to the judges.”

The team also benefited from Berkeley’s unique Interdisciplinary Graduate Certificate in Real Estate program, allowing us to take classes at Haas, the College of Environmental Design, and Berkeley Law, Valchuis said. “As a result, we demonstrated a cohesive understanding of the social, political, and financial impacts of our investment that may have been more difficult for other schools to match.”

Can an MBA help build a career in property?

Space, Reimagined

Haas alumni rethink our physical world.

Street curbs used to serve one purpose: to keep pedestrians and vehicles from colliding. Today, they are microcosms of urban bustle. Cars, buses, delivery trucks, bikes, scooters, pedestrians, and, increasingly, roaming robots all jockey for finite space. As the COVID-19 pandemic lingers, restaurants, too, have spilled onto sidewalks and into streets.

Gene Oh, BS 99, looks at this curbside jam and sees opportunity for disruption. “There’s a huge supply-demand mismatch,” says Oh, CEO of urban transit planning and operations company Tranzito. “And autonomous vehicles and drones will only make this mismatch larger.”

Gene Oh, BS 99, looks at this curbside jam and sees opportunity for disruption. “There’s a huge supply-demand mismatch,” says Oh, CEO of urban transit planning and operations company Tranzito. “And autonomous vehicles and drones will only make this mismatch larger.”

Oh believes that curbs, especially on-street parking and bus stops, need to be repurposed for this smart cities future. Imagine, for example, clusters of sidewalk lockers for delivery drop-offs and reservable spaces for delivery and car-service drivers.

and bikes, are vying for curb space along with ride-hailing services, mass transit, on-demand delivery vehicles, restaurants, and pedestrians. Curb space needs to be rethought and streamlined, say members of the Haas community.

Benjamin Fong, MBA 17, says the implications of street design go beyond logistics and human safety. “The road is a metaphor for society,” says Fong, a former Berkeley city planning commissioner. “It reflects how we work with each other and interact with each other on a very subconscious level.”

Benjamin Fong, MBA 17, says the implications of street design go beyond logistics and human safety. “The road is a metaphor for society,” says Fong, a former Berkeley city planning commissioner. “It reflects how we work with each other and interact with each other on a very subconscious level.”

To Fong, our streets represent an existential crisis. “We’ve lost our connection with each other,” he says. Sheltering in place and social distancing during the pandemic, he adds, have made us acutely aware of the physical boundaries that limit us.

Fong is not the only one who sees this disconnect. Conversations with 15 Berkeley Haas alumni and faculty who think deeply about the spaces in which we live and work reveal a paradox: As much as we try to avoid each other to stay healthy, our need for in-person connections has never been greater. Technology plays an important role—but in ways that are often less sci-fi than we might think.

“The silver lining of COVID-19 is that we have the perfect opportunity to experiment with our spaces,” says Fong, who serves as director of business development at e-scooter sharing company Spin, a Ford subsidiary. “Now is the time for us to figure out how to use our physical surroundings to build stronger communities and in ways that are more human-centric.”

“Now is the time for us to figure out how to use our physical surroundings to build stronger communities and in ways that are more human-centric.”

—Benjamin Fong, MBA 17

Urban Concerns

No one, of course, has a crystal ball. COVID-19, Black Lives Matter, economic devastation, and climate change are all powerful forces that promise to reshape society in ways that cannot be foreseen. Some crises may simply accelerate preexisting trends.

Molly Turner, a Haas lecturer and expert on technology’s impact on cities, says one outcome is all but certain: The pandemic will catalyze sweeping changes in our way of life.

Molly Turner, a Haas lecturer and expert on technology’s impact on cities, says one outcome is all but certain: The pandemic will catalyze sweeping changes in our way of life.

“Some of our most transformative urban innovations have been a result of public health crises,” says Turner, who co-hosts the podcast Technopolis (haas.org/technopolis-podcast), about technology and urban environments. “We developed flushing toilets, urban parks, and aqueducts so our cities would be more safe and sanitary and allow us to live in high density with each other.”

But the pandemic won’t empty out cities for good, says Turner. “Big cities are not dead because of COVID-19,” she says, noting that past predictions of de-urbanization in the face of health threats never panned out. Similarly, the advent of telecommunications was expected to inspire a mass city exodus as people realized they could connect from afar without the high costs of urban living. “Enough people still chose to live in cities so they could be in close physical proximity to each other,” she says.

By necessity, however, cities will have to change beyond figuring out how to get workers safely into offices. For example, if retailers move the bulk of their sales online, empty storefronts will need to be filled. Some cities already are thinking about converting vacant office spaces into residences.

Victor Santiago Pineda, BS 03, BA 03 (political economy), MCP 06 (city and regional planning), reimagines cities as more accessible. A globally recognized urbanist and social impact entrepreneur, Pineda stands by the United Nations’ pre-COVID predictions that by 2050 two-thirds of the world’s population will live in urban areas. Yet, he says, 70% of the infrastructure needed to accommodate that growth hasn’t been built yet.

“This is, unquestionably, the urban century,” says Pineda. “[But] nearly everything that humanity has built since the inception of cities will need to double to keep up with population’s demand.”

As president of World Enabled, a global education and consulting group shaping more inclusive societies, Pineda helps empower leaders to build better cities for people with disabilities and older persons. Pineda himself has used a wheelchair and other assistive technology since childhood and has for nearly 20 years worked with the UN and businesses to ensure that disability rights are seen as human rights. “Our cities are failing us,” he says.

To be accessible and inclusive, cities and private organizations need to unlock data-driven “inclusive innovation” to accommodate the unmet needs of nearly 600 million people with disabilities who live in cities, says Pineda. For example, how will AI, blockchain, delivery robots, and drones frustrate or enhance access for people with visual, hearing, mobility, or intellectual impairments? Are companies thinking about the co-benefits of smart, green, and inclusive design?

Via World Enabled and UC Berkeley’s Inclusive Cities Lab, an interdisciplinary research initiative that Pineda founded and directs, he’s launched a global campaign to ensure 100 cities prioritize inclusion and accessibility as they build infrastructure, both physical and digital, over the next 50 years. To date, New York, Berlin, Rio de Janeiro and 27 other municipalities have signed onto the Cities4All initiative, which plans to measure progress via an inclusive cities index.

“Everything we do to address climate change, racial and gender inequality, education, and employment will be won or lost depending on whether we get our physical infrastructure right,” says Pineda.

The nomadic workplace

Of all the trends catalyzed by the pandemic, the shift to remote work was especially swift. Almost overnight, lockdowns forced millions of U.S. workers to turn spare rooms, tabletops, and even closets into fully functioning offices.

Companies such as Facebook, Twitter, Microsoft, and Dropbox have moved to allow more, or even all, of their employees to work remotely. As more companies follow their lead, Jennifer Chatman, a Haas professor and expert on workplace culture, says the traditional downtown corporate office is headed for a massive shakeout.

Companies such as Facebook, Twitter, Microsoft, and Dropbox have moved to allow more, or even all, of their employees to work remotely. As more companies follow their lead, Jennifer Chatman, a Haas professor and expert on workplace culture, says the traditional downtown corporate office is headed for a massive shakeout.

“I believe within five years, the real estate footprint of most nonmanufacturing organizations will decline by 50% to 75%,” says Chatman, the Paul J. Cortese Distinguished Professor of Management.

With less square footage, companies will instead embrace hybrid workplaces. Some employees will stay home permanently or rotate with others through spaces reconfigured into fewer offices.

The dominant feature will be large collaboration rooms where small groups of employees can brainstorm and engage in the kind of spontaneous interactions that she calls the lifeblood of culture and organizational life.

Cristina Banks, a Haas senior lecturer and director of the Interdisciplinary Center for Healthy Workplaces, also expects to see shifts away from traditional corporate settings to more flexible work arrangements in the home, coffee shops, or neighborhood “coworking” spaces.

Cristina Banks, a Haas senior lecturer and director of the Interdisciplinary Center for Healthy Workplaces, also expects to see shifts away from traditional corporate settings to more flexible work arrangements in the home, coffee shops, or neighborhood “coworking” spaces.

One fad that is unlikely to outlast COVID-19? The so-called socially distanced office of six-foot safety precautions, one-way hallways, and plexiglass dividers that have dominated discussions of returning to work. “We already know these measures aren’t working,” says Banks. “An engineering approach to social distancing won’t work unless it also takes human behavior into account.”

Simpler ways of living

Even before COVID-19, Eric Cress, MBA 04, was seeing a desire for fresh innovation among homebuyers and renters—namely, a thirst for stronger community through physical interaction.

Even before COVID-19, Eric Cress, MBA 04, was seeing a desire for fresh innovation among homebuyers and renters—namely, a thirst for stronger community through physical interaction.

“When you’re living in an apartment or condominium, you’re so close to other people, but you don’t have that neighborhood feel,” says Cress, a principal at Urban Development + Partners in Portland, Oregon.

Cress says a growing number of buyers—from young city dwellers to retiring baby boomers—approach him to build their own communities. Typically, these are either condos or stand-alone houses that surround large common areas where residents come together to dine or do chores. The size of the “cohousing” development varies, but the common link is that dwellers seek to develop meaningful relationships with others.

“Everything we do to address climate change, racial and gender inequality, education, and employment will be won or lost depending on whether we get our physical infrastructure right.”

—Victor Santiago Pineda, BS 03

“The idea is to recreate the neighborhood from your youth, where everyone around you knew each other,” says Cress. While cohousing is still a niche, he says interest is growing and has spiked during COVID-19. His firm now has nine cohousing projects in the works, up from one development five years ago. “For a lot of buyers,” he says, “it’s about getting back to basic human needs.”

Physical + virtual space

Last March, the coronavirus had Alejandro Maldonado, EMBA 16, and his team scrambling. His company, HUM, offers an artificial intelligence platform for helping property developers and managers sell living spaces. But it was meant for showrooms, not home lockdowns. For three weeks, they raced to build an entirely new application so prospective homebuyers and renters could tour dwellings remotely.

Last March, the coronavirus had Alejandro Maldonado, EMBA 16, and his team scrambling. His company, HUM, offers an artificial intelligence platform for helping property developers and managers sell living spaces. But it was meant for showrooms, not home lockdowns. For three weeks, they raced to build an entirely new application so prospective homebuyers and renters could tour dwellings remotely.

Maldonado, HUM’s CEO, says the pandemic forced the real estate industry to wake up to strong consumer disdain for the homebuying and renting process, an experience that can be enlivened with virtual technology.

“Most people have a difficult time envisioning an unbuilt or empty property, and that’s stressful,” says Maldonado. “They want more personalization and customization.”

Omar Téllez, MBA 96, also sees a merging of physical and virtual worlds for the better. He first saw that promise as the founding president of Moovit, the popular mobility-as-a-service provider that Intel bought this spring for $900 million. Moovit helps 865 million users in 3,200 cities worldwide plan their transportation.

Omar Téllez, MBA 96, also sees a merging of physical and virtual worlds for the better. He first saw that promise as the founding president of Moovit, the popular mobility-as-a-service provider that Intel bought this spring for $900 million. Moovit helps 865 million users in 3,200 cities worldwide plan their transportation.

Today, Téllez is thinking about how 5G cellular networks will revolutionize human experience. That’s because Téllez serves as vice president for strategic partnerships at Niantic, the Pokémon GO mobile game maker founded by classmate John Hanke, MBA 96. In August, his team announced a major alliance with some of the world’s largest telcos that Téllez says will finally enable spectacular integrations of our physical and virtual worlds.

“With 5G technology, the glitches or latencies that limit virtual experiences on the phone or with alternative-reality glasses have gone away,” says Téllez. Now, app developers like Niantic can overlay images onto the physical world, smoothly enabling more social and immersive experiences. Imagine, for example, going to a park to play Minecraft with friends and the actual trees become part of your Minecraft landscape.

The speed, versatility, and stability of 5G communications will touch every aspect of our lives, Téllez says. The “smart city” will no longer be just a buzzword. Cameras and sensors will enable near real-time responses to changes in curbside traffic flows or energy use. Tourists could instantly learn about historic landmarks by looking at them via virtual-reality glasses. Commuters will see departure times superimposed onto subway entrances.

“5G promises to completely transform the way people interact with each other and the world around them, says Téllez. “When these two worlds—the physical and the virtual—collide, it will create beautiful new places, and we will all be better off.”

Housing for all

Michelle Boyd, MBA 19, is the program director of the Housing Lab, a UC Berkeley accelerator for ventures addressing the high cost of housing via finance and construction solutions, creative living models, and technology platforms. In California alone, she says, there’s a critical need to build two million houses in the next 10 years. But with the cost of a single subsidized housing unit in San Francisco reaching $1 million, practical remedies can seem elusive.

Still, Boyd sees some promising ideas in her lab, an initiative within the Terner Center for Housing Innovation—for example, Factory OS and Project Frog, which manufacture entire walls and other building components offsite. Terner Center research has found that so-called modular construction could reduce construction costs by 20% or more and building time by up to 40%.

“Many of these exciting ideas are still unproven. No one has really figured out how to build affordably and well in expensive markets.”

—Michelle Boyd, MBA 19

Other solutions include accessory dwelling units, which homeowners install in their backyards and can rent—often at below-market rates because construction costs range from $50,000 to $250,000 depending on locale. Boyd is also optimistic about innovations in finance and construction that can make it easier to build “missing middle housing.” These are duplexes, say, or a fourplex, often built in single-family neighborhoods that mesh aesthetically and can be rented at affordable rates. The idea is to help those who are priced out of expensive markets but don’t qualify for low-income subsidies.

But like many affordable housing solutions, the cost remains high. “Many of these exciting ideas are still unproven,” says Boyd. “No one has really figured out how to build affordably and well in expensive markets.” Even so, she’s hopeful that, in a year of pandemic and protests, local and state governments may finally have the political support to address policies that perpetuate high living costs and the social inequities they perpetuate. “If we play our cards right,” she says, “there’s an opportunity for us to reimagine cities in ways that are more equitable.”

Arthur Bretschneider & Sushanth Ramakrishna, MBA 16s

Co-founders, Seniorly

Searching online for senior living can be a complicated endeavor with many variables, including nonmedical care, assisted living, memory care, and nursing homes.

Searching online for senior living can be a complicated endeavor with many variables, including nonmedical care, assisted living, memory care, and nursing homes.

Enter Seniorly, a free technology portal to help aging adults find appropriate housing—and feel at home.

Classmates Arthur Bretschneider and Sushanth Ramakrishna conceived of Seniorly during their first year at Berkeley Haas.

Bretschneider is no stranger to the senior living industry—it’s the family business. His grandfather built retirement homes in the 1950s, and he grew up helping his dad run the business.

Bretschneider knows it can be confusing to find not only what’s available but also the best match. “We wanted to offer a data-driven but friendly way for families to navigate this process,” he says.

Since its launch in 2015, Seniorly has featured more than 35,000 properties nationwide. But the company also connects families to local agents who can help with everything from completing an application and brokering a contract to moving.

“Adding the agents into our model is exciting,” Ramakrishna says. “Many of the agents are local independent businesses, and they know their area. It brings a sense of community to the process.”

Adds Bretschneider: “Finding a good place for aging parents to live is usually a once-in-a-lifetime process, and families need support. We want to make it as easy and transparent as possible, while also bringing community to the forefront.”

House Pall

A warning about the mortgage industry

As millions of laid-off Americans struggle to make housing payments during the pandemic, Prof. Nancy Wallace issues a dire forecast: the mortgage industry itself could collapse.

For more than two years, Wallace and Prof. Richard Stanton have been raising the alarm that fragile “nonbank” lenders have grown to dominate the market, originating two-thirds of all single-family home loans—up from 20% in 2007—but are subject to little oversight. They have scant capital of their own or access to emergency cash, and they also target more vulnerable borrowers who are more likely to miss payments early on, their research has found.

It is another disaster waiting to happen, they warn. During the pandemic, homeowners have been given a temporary payment reprieve by the federal rescue package, which meant plummeting cash flows for nonbanks.

In the short run, vulnerable nonbank lenders have been saved from bankruptcy by rock-bottom interest rates that spurred a wave of refinancing and new loan originations. They also got government backup from Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac.

“Defaults are on the rise,” Wallace says. “A lot depends on what happens with unemployment and how long this drags on, but my position remains that nonbank lenders are in a very precarious position.”

Wallace argues that any government assistance should have come with a quid pro quo: future fees and increased oversight. “Nonbank lenders can’t keep pushing the envelope then expect to be rescued. They don’t want to follow any of the rules that banks follow, and then they want to be treated like banks when liquidity shocks occur.”

Karlene Roberts

Karlene Roberts