Fewer managers, more tech talent: How early AI investments rewired company org charts

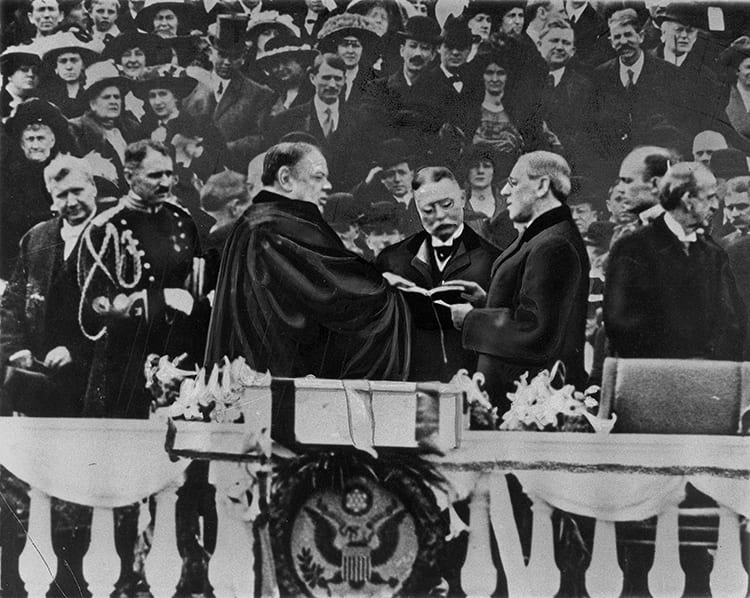

Before the election of President Woodrow Wilson, Black Americans worked at all levels of the federal government. But when Wilson assumed office in 1913, he mandated that the federal workforce be segregated by race—leading to the reduction of Black civil service workers’ income, increasing the significant income gap between Black and white workers, and eroding some of the gains Black people had made following Reconstruction.

That’s the finding of a recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper by Berkeley Haas Asst. Prof. Guo Xu and Berkeley Law Asst. Prof. Abhay Aneja, PhD 19, who examined how Wilson’s far-reaching segregation policy affected Black workers relative to white workers during the same era.

“The segregation of the federal civil service is a dark chapter in the history of the American government that has been relatively understudied,” Xu says. “Persistent racial inequality remains a major challenge in this country, and we felt it was important to provide systematic quantitative evidence on the economic costs of such episodes of state-sanctioned discrimination.”

The segregation of the federal civil service is a dark chapter in the history of the American government that has been relatively understudied. —Guo Xu

Surprise segregation order

Though Black voters had historically supported the Republican Party, Wilson, a Democrat, gained the support of many Black voters—including W.E.B. Dubois, Booker T. Washington, and Monroe Trotter—due to his campaign promise of equal treatment. His racial segregation order “came swiftly and suddenly, taking Black Americans by surprise,” the researchers wrote. Wilson imposed segregation in his Cabinet departments, and appointed Southern Democrats, who were likely in favor of segregationist policies, to lead them.

The researchers point out that unlike the purported “separate but equal” policies of the Jim Crow era, Wilson’s order was overtly discriminatory. “Wilson’s segregation directive was designed to limit the access of Black civil servants to white-collar positions via both demotions and the failure to hire qualified Black candidates,” they wrote.

Segregation was implemented first at the Post Office, which was home to over 60% of federal jobs at the time and employed many Black workers, and next at the Treasury Department, which had the second largest number of Black workers. To examine how Wilson’s segregation mandate affected them, the researchers relied on several historical data sources. First, they digitized the 1907–1921 U.S. Official Registers, which list every person who worked for the federal government. They also used personnel records from the U.S. Postal Service, and linked them to the 1910 U.S. Census.

Segregation increased the salary gap

On average, Black workers held lower-paying jobs than white workers prior to the segregation mandate. Across all departments and jobs, black civil servants earned on average 37% less than white civil servants in 1911, driven largely by the fact that they were disproportionately represented in lower paid and menial jobs.

To isolate the effect of the segregation policy, the researchers needed to look at people in comparable positions. They did this by matching Black workers to similar white workers in the same department with similar levels of experience and pay before Wilson’s term in 1919. Comparing these equally situated black and white civil servants after the implementation of the segregation policy, they found that the Black-white earnings gap in the civil service increased by about 7 percentage points between 1913 and 1921–a big effect that increased the existing earnings gap by almost 20%.

“We were struck by how damaging the policy was on the careers of Black civil servants, even after Wilson left office,” Xu says.

We were struck by how damaging the policy was on the careers of Black civil servants, even after Wilson left office…If such effects last beyond generations, it could crucially matter for the design of policies that are aimed at closing the painfully persistent racial inequities we observe today. —Guo Xu

The negative effects were largest in departments that strictly enforced the segregation order, such as the Post Office and the Treasury. The Agriculture Department, which initially resisted the segregation order, saw smaller effects

The researchers found evidence that Black workers were more likely to be demoted and were more likely to enter the federal workforce at lower levels following the order. For example, while Black workers had held 13.1% of the highest-ranking postmaster positions, the order led to a 7% decline.

Xu and Aneja are next working to understand whether these deleterious effects have persisted to the next generation of family members connected to the affected workers.

“If such effects last beyond generations, it could crucially matter for the design of policies that are aimed at closing the painfully persistent racial inequities we observe today,” Xu says.

Posted in:

Topics: