Two top-tier researchers whose work addresses pressing environmental, development, and public policy questions have joined the ranks of Berkeley Haas professors this semester. Two additional professors will join the faculty in January 2025.

“Our new faculty hires this year are leading researchers and teachers who will help to solidify our emphasis on sustainability,” says Interim Dean Jenny Chatman. “We’re so thrilled they are bringing their brilliance to Haas—and to the greater UC Berkeley community.”

“Our new faculty hires this year are leading researchers and teachers who will help to solidify our emphasis on sustainability. We’re so thrilled they are bringing their brilliance to Haas—and to the greater UC Berkeley community.” —Interim Dean Jenny Chatman

Associate Professor Kelsey Jack, whose work lies at the intersection of environmental and development economics, comes to Haas from the University of California, Santa Barbara, where she was an associate professor at the Bren School of Environmental Science and Management and the Department of Economics.

Professor James Sallee is already a familiar face around campus. As a faculty member in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at UC Berkeley since 2015 and a faculty affiliate at the Energy Institute at Haas since 2016, his research focuses on energy, the environment, climate, and public economics, with a focus on public policy.

In January, Berkeley Haas will welcome Economist Martin Beraja of MIT will join the Economic Analysis and Policy group as an assistant professor, and Dr. David Chan, a health economist and MD now at Stanford University, will join the Economic Analysis and Policy group as a professor. Chan will serve as the new faculty director for the Robinson Life Science, Business, and Entrepreneurship Program.

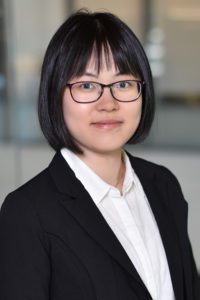

Associate Professor Kelsey Jack, Sheth Sustainable Business Chancellor’s Chair

Pronouns: she/her

Pronouns: she/her

Hometown: Van Zandt, Washington

Academic Group: Business and Public Policy

Education:

- PhD, Public Policy, Harvard University

- AB, Public and International Affairs, Princeton University

Research focus: Environmental and development economics

Introduction: I am joining Haas from the University of California, Santa Barbara, where I was an associate professor at the Bren School of Environmental Science and Management and the Department of Economics. Prior to that, I was an associate professor at Tufts University. I also spent a year at UC Berkeley in 2013-14 as visiting faculty in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics.

I study questions at the intersection of environmental and development economics. In particular, I try to understand how low income households use natural resources—land, water, energy—and the ways that policy can help align short-run economic needs with longer-run environmental and health concerns. I’ve thought about this topic for a long time, since a family trip to Madagascar after my freshman year in high school; it’s remained the problem that interests me most in the world. For example, at the moment, I’m studying climate adaptation in Niger and clean energy adoption in Ghana. I have other projects underway in India, South Africa, Malawi and Ivory Coast.

“I try to understand how low income households use natural resources—land, water, energy—and the ways that policy can help align short-run economic needs with longer-run environmental and health concerns. I’ve thought about this topic for a long time, since a family trip to Madagascar after my freshman year in high school.” —Associate Professor Kelsey Jack

Teaching: I am creating a new course, tentatively titled “Sustainable Markets: Profit, Policy, and Corporate Responsibility”

Why you decided to join Berkeley Haas: Amazing colleagues!

Fun (nonacademic) fact about you: I spent two years after college living in Vientiane, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Laos) working for an environmental organization and figuring out what to do with my life.

Professor James Sallee

Pronouns: he/him

Pronouns: he/him

Hometown: Bloomington, Illinois

Academic Group: Economic Analysis and Policy

Education:

PhD, Economics, University of Michigan

BA, Economics and Political Science, Macalester College

Research focus: Energy, the environment, climate, and public economics, with a focus on public policy

Introduction: I always knew that I wanted to be an academic, to research, write and teach. So I went more or less straight through to my PhD after college. I fell in love with economics towards the end of college because I saw it as a versatile tool that could be used to study a variety of important problems. In graduate school, I was studying tax policy, partly because it interested me and partly because that was where I found the best mentorship. But, I fell almost by accident into a dissertation topic that studied tax subsidies for hybrid cars. As I learned more about environmental issues, I became more and more interested, and my career has ever since drifted more and more towards the biggest environmental problems of the day. I now study topics ranging from retail electricity pricing reforms in California to the design of public policies to ensure equity in the energy transition. For the last several years, I’ve worked with collaborators in the Rausser College of Natural Resources and at Haas to launch a brand new master’s program called the Master of Climate Solutions, which will be an interdisciplinary professional program that equips students to help become change agents for the climate across industries and sectors.

“As I learned more about environmental issues, I became more and more interested, and my career has ever since drifted more and more towards the biggest environmental problems of the day. I now study topics ranging from retail electricity pricing reforms in California to the design of public policies to ensure equity in the energy transition.” —Professor James Sallee

Class(es) you’ll teach: Core microeconomics

Why you decided to join Berkeley Haas: I have always loved professional education because it feels impactful to help equip students who are going to jump back into leadership roles right after school. I like the back-and-forth with students who bring not just intellectual curiosity, but also a wealth of experience to the classroom dialogue. I like that professional students demand that material is relevant and practical. I was also drawn to the opportunity to push Haas as the leader in climate and sustainability. My research and policy attention has moved more and more towards the climate challenge in recent years, and I believe that business can and must drive progress on climate.

Fun (non-academic) fact about you: I spent most of my money and all of my energy outside of work taking care of my three daughters. I love to travel and enjoy cooking.

Professional Faculty

In addition to the new members of the ladder faculty, nine new lecturers will be teaching courses this fall. Several others will join in spring (with additions exepected mid-year). They include:

- Helene York, Responsible Business

- Kate Gordon, Sustainable & Impact Finance

- Rebekah Butler, Business & Public Policy

- Alex Luce, Economic Analysis & Policy

- Ana Martinez, Economic Analysis & Policy

- Miyoko Schinner, Sustainable & Impact Finance

- Jules Maltz, Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Richard Wuebker, Finance

- Asiff Hijiri, Finance/Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- queen jaks, Management of Organizations (spring 2025)

- Bianca Datta, Sustainable & Impact Finance (spring 2025)

Berkeley — A team of researchers who developed tools for investors, academics, and businesses to measure economic risks from the loss of the planet’s biodiversity has won the inaugural

Berkeley — A team of researchers who developed tools for investors, academics, and businesses to measure economic risks from the loss of the planet’s biodiversity has won the inaugural

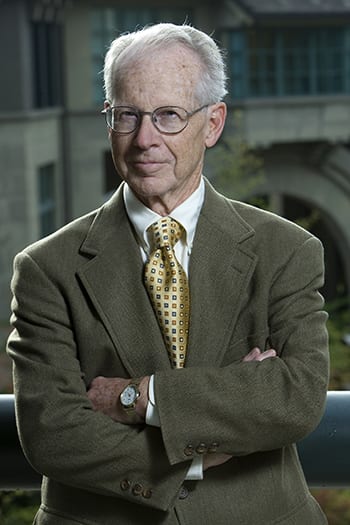

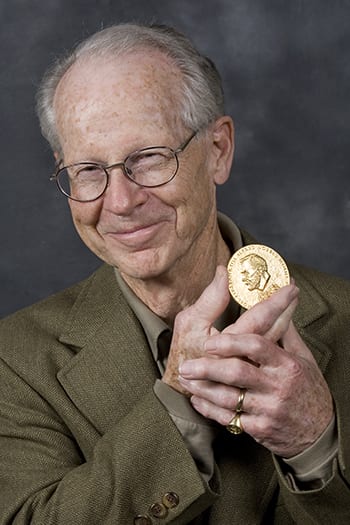

Berkeley Haas Prof. Emeritus

Berkeley Haas Prof. Emeritus  Throughout his life, Williamson displayed an uncommon humility even as his celebrity in economic circles grew. Just hours after his Nobel Prize was announced, Williamson was modest about his selection, calling it “undeserved” during a congratulatory toast with hundreds of Haas faculty, staff, and students.

Throughout his life, Williamson displayed an uncommon humility even as his celebrity in economic circles grew. Just hours after his Nobel Prize was announced, Williamson was modest about his selection, calling it “undeserved” during a congratulatory toast with hundreds of Haas faculty, staff, and students.

With 5% of the world’s population and 25% of its prisoners, the United States is the most punitive country in the world. Among developed countries, the disparities are even more striking: The U.S. relies on incarceration for 70% of criminal sanctions, while in Germany, it’s 6%.

With 5% of the world’s population and 25% of its prisoners, the United States is the most punitive country in the world. Among developed countries, the disparities are even more striking: The U.S. relies on incarceration for 70% of criminal sanctions, while in Germany, it’s 6%.