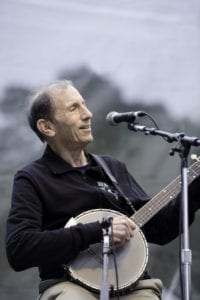

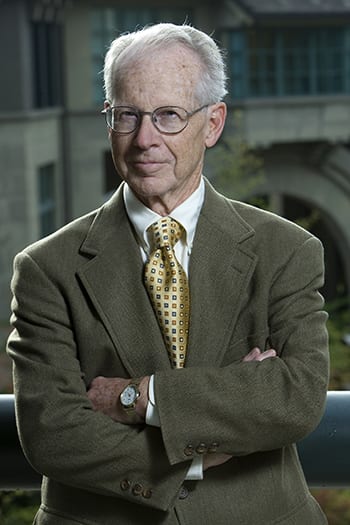

Professor Emeritus Thomas Marschak, an economist who influenced generations of students during almost 60 years of active research and teaching at Berkeley Haas, passed away Jan. 31 at his Oakland home. He was 93.

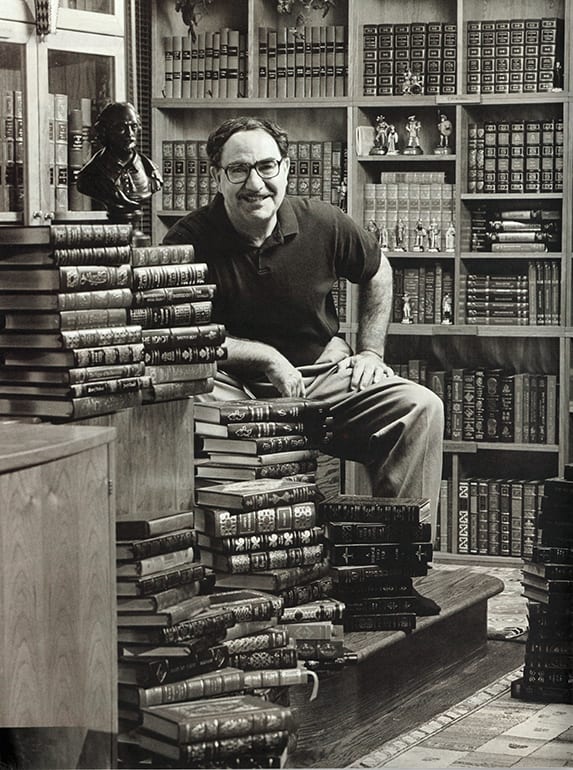

Marschak, the Cora Jane Flood Research Chair Emeritus, was known for his dry humor, his generous mentorship, and his research into the design of efficient organizations.

“In so many ways, Tom was way ahead of his time,” said Professor Rich Lyons, UC Berkeley Associate Vice Chancellor for Innovation & Entrepreneurship and former dean of Berkeley Haas. “When you think about the center of gravity of his work—the informational and incentive aspects of the design of efficient organizations—you realize quickly that these topics are becoming ever more important.”

As a member of Haas’ Economic Analysis & Policy Group and Operations & IT Management group, Marschak continued his boundary-spanning research into his 10th decade. Just two weeks before his death, he had a paper accepted to the Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics.

“Tom was one of the sharpest, most insightful, and most admirable economists I have ever seen,” said Dong Wei, PhD 20 (economics), an assistant professor of economics at UC Santa Cruz who co-authored the recent paper with Marschak. “He had a tremendously successful academic career, and at the age of 90, he was still developing novel research ideas, conducting economic analysis with advanced mathematical tools, and writing academic papers with extreme rigor and clarity.”

“In so many ways, Tom was way ahead of his time. When you think about the center of gravity of his work—the informational and incentive aspects of the design of efficient organizations—you realize quickly that these topics are becoming ever more important.” —Professor Rich Lyons

Fleeing Nazi Germany

Marschak was born in Heidelberg, Germany, in 1930. His father, Jacob, who was Jewish and from Kyiv, Ukraine (then part of Russia), was a notable figure: As a 19-year-old student opposed to Lenin and the Bolsheviks, he served as labor secretary in a separatist republic in the Caucasus that lasted less than a year. When the Bolsheviks prevailed, Jacob Marschak—who went on to become a prominent economist—fled to Berlin. There, he met Tom Marschak’s mother Marianne, a journalist who earned her PhD and became an influential psychologist, developing the Marschak Interaction Method for observing the relationship between caregivers and children.

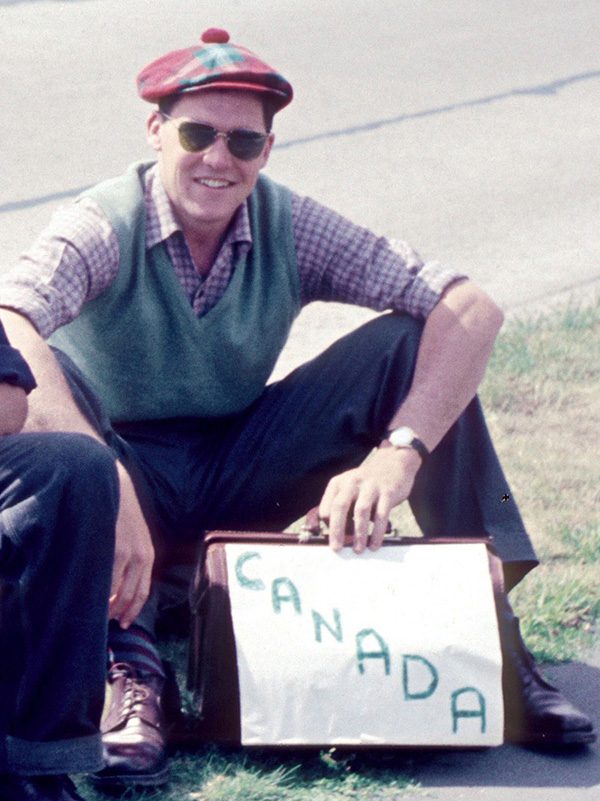

Although Tom’s early life in Germany was sunny, the looming threat of Nazism cast a shadow. In 1933, when Tom was 4 years old, his father insisted they flee to the United Kingdom. It was a prescient move as the family escaped the horrors of the Holocaust.

Marschak spoke about his father’s foresight in an oral history he recorded in 2005. “That was amazing foresight because all the other Jewish people with that kind of position said, ‘It’ll pass, it’s nothing, it’s a civilized country,’” Marschak said in the oral history. “He knew better.”

In England, Jacob Marschak was made a fellow of All Souls College at Oxford University while young Tom and his sister were put into school—taught in English, a language he had to learn quickly. In 1939, as the war spread, the family decamped to the United States. As they were not British citizens, and Germany had withdrawn citizenship from Jews, they were stateless for a time. Still, with the help of Tom’s father’s academic friends, they settled in New York, where Jacob Marschak took a position at the New School for Social Research.

In 1943, the family moved to Chicago, where Marschak went to University High School—an experimental school attached to the University of Chicago where students could graduate high school in 10th grade and get a bachelor’s degree by 12th grade. The Marschak home during that period was host to a circle of prominent émigrés, including Leo Szilard, the physicist who discovered the nuclear chain reaction process; atomic physicist Hyman Goldsmith; violinist Isaac Stern; and Edward Teller, the father of the hydrogen bomb.

By age 17, Marschak was a college graduate, with honors. He landed on economics as his field of study and headed to Stanford for his doctorate, followed by a job at RAND Corp. in Santa Monica under Charlie Hitch (later president of the University of California).

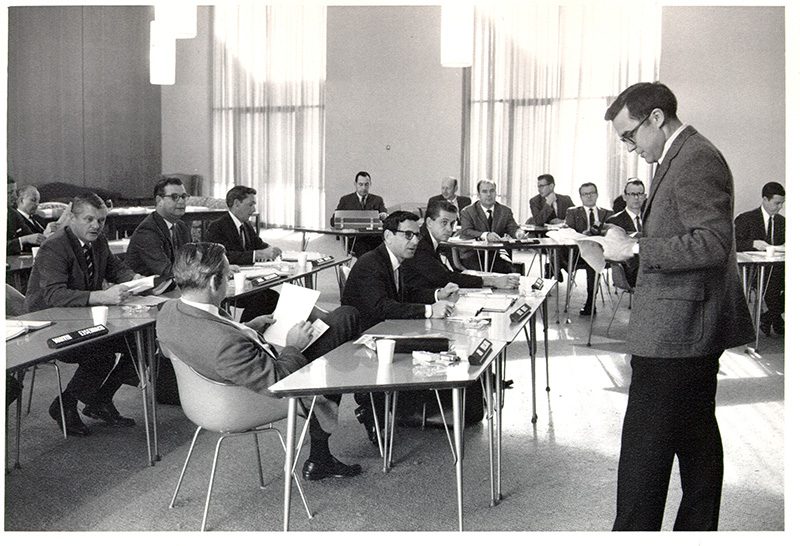

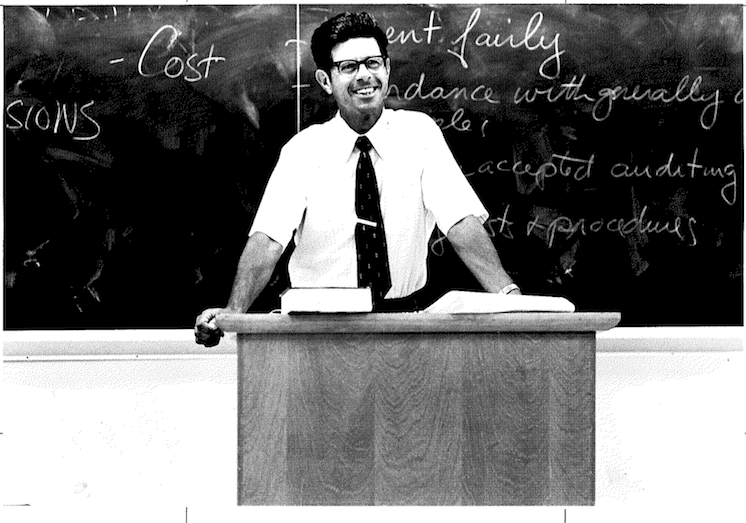

In 1960, he was hired as an associate professor at Berkeley Haas. “Things were very different then,” he recalled later. “You dressed in a white shirt and a tie, I can’t believe that. I was one of the very first to grow a beard—almost unheard of.”

Marschak lived in Berkeley with his first wife, Dorothy, and their children Debbie, Madeline, and Timothy. In 1968, Marschak’s life was scarred by tragedy when his eldest daughter Debbie, age 10, died in a car accident.

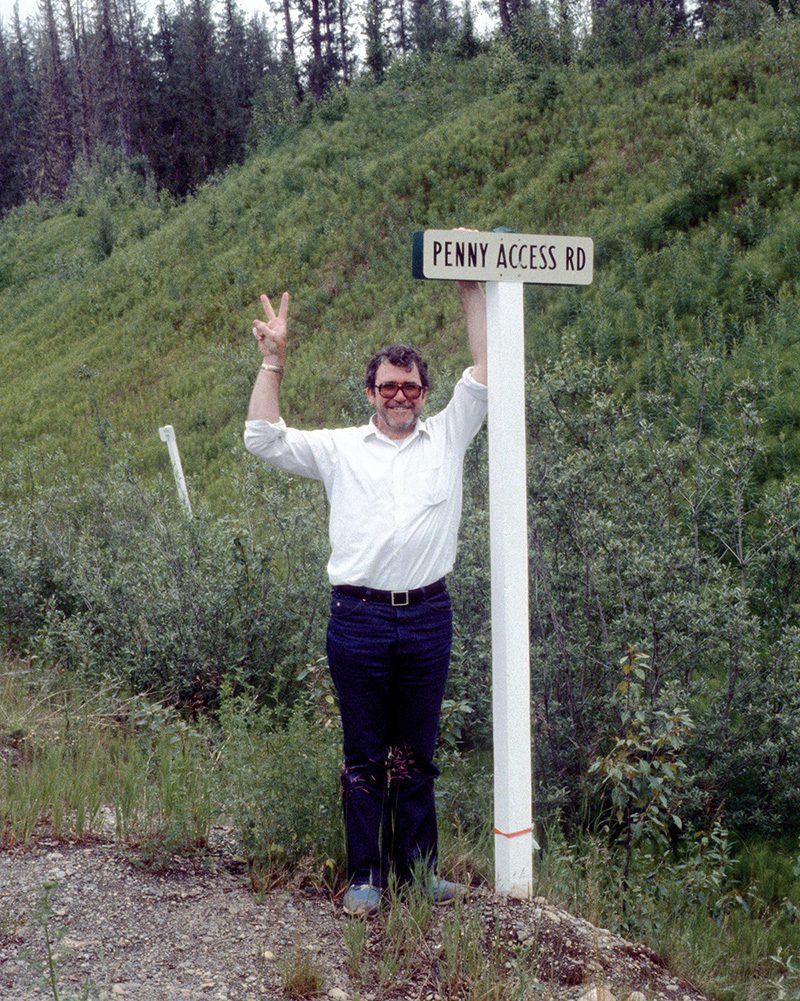

In 1979, he remarried, and he and his wife Merideth had sons Anthony and Daniel. He was a devoted and deeply involved father. “He took us to film festivals, summer backpacking and river trips, enrolled us in summer programs, monitored our education, and kept us in close contact with his side of the family,” recalled daughter Madeline Marschak. “He offered all four of his children unconditional love and support equally. …Tom Marschak was my hero and the best father anyone could hope to have.”

Academic boundary spanner

Academically, Marschak made his mark in economics theory, studying information gathering, information technology, and network mechanisms—complex work that was ahead of its time, Lyons said.

“Tom was an intellectual boundary-spanner from the get-go, having spanned two academic groups at Haas and having spanned in his work even more areas than these two groups traditionally have done,” Lyons said. “His work covered IT, data science, use of data to drive enterprise value: These are some of the defining issues of our current time.”

Marschak was the co-winner of the Koç University prize in 1996. He was an elected fellow of the Econometric Society and the recipient of both a Fulbright-Hays research award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Ford Foundation faculty research fellowship.

“Much of Tom’s work addressed foundational issues of organizational design, such as how the degrees of hierarchy or decentralization affect an organization’s communication costs and ability to achieve its objectives,” said Professor Emeritus Michael Katz, Sarin Chair Emeritus in Strategy and Leadership. “Although this work was abstract, it has important implications for business organizations.”

‘Dry and delicious humor’

His colleagues at Haas remember him as a generous instructor with a wry sense of humor. “Tom taught microeconomics to a generation of Haas undergraduates,” said Professor Emeritus Jonathan Leonard, George Quist Chair in Business Ethics. “If you could get him to raise an eyebrow, you knew you had said something interesting.”

Merideth Marschak also recalled her husband’s “dry and delicious” humor, as well as his love for outdoor hiking adventures and walking the Bay Area hills up until his last months. He was “unbeatable at trivia and could summon up historic facts and arcane knowledge on request” and also loved to cook for friends and family. “A crowded dinner table was the best fun,” she added. He was delighted when he became a grandfather at age 88.

“He was incredibly generous with his insight and his kindness,” Merideth Marschak said. “He taught us all the value of slowing down, enjoying life, and keeping an open mind.”

Marschak is survived by his wife, Merideth; his children, Madeline, Timothy, Anthony, and Daniel; his granddaughters Lucy and Alice; and nieces Emily and Julie Jernberg. He was predeceased by his sister, Ann Jernberg.

Berkeley Haas Prof. Emeritus

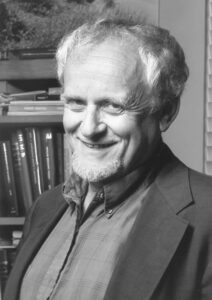

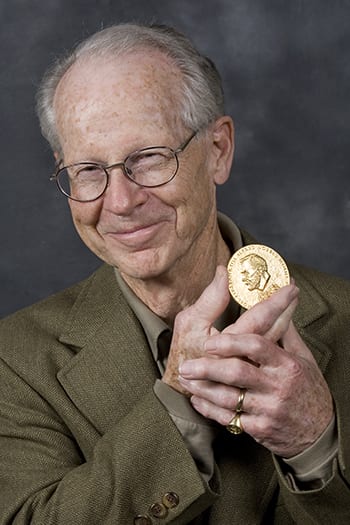

Berkeley Haas Prof. Emeritus  Throughout his life, Williamson displayed an uncommon humility even as his celebrity in economic circles grew. Just hours after his Nobel Prize was announced, Williamson was modest about his selection, calling it “undeserved” during a congratulatory toast with hundreds of Haas faculty, staff, and students.

Throughout his life, Williamson displayed an uncommon humility even as his celebrity in economic circles grew. Just hours after his Nobel Prize was announced, Williamson was modest about his selection, calling it “undeserved” during a congratulatory toast with hundreds of Haas faculty, staff, and students.

Real estate and finance professor Dwight M. Jaffee passed away peacefully on Thursday, January 28, 2016, in San Francisco, CA, at the age of 72.

Real estate and finance professor Dwight M. Jaffee passed away peacefully on Thursday, January 28, 2016, in San Francisco, CA, at the age of 72.

Alumnus and entrepreneur Hansoo Lee, MBA 10, passed away March 4 after a 15-month battle with lung cancer. A memorial for Lee was held today in San Francisco, and classmates are currently setting up an entrepreneurship fellowship in his name.

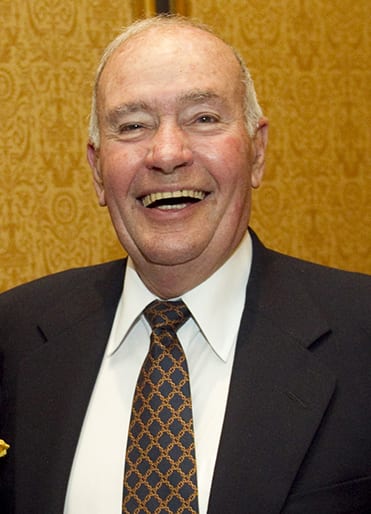

Alumnus and entrepreneur Hansoo Lee, MBA 10, passed away March 4 after a 15-month battle with lung cancer. A memorial for Lee was held today in San Francisco, and classmates are currently setting up an entrepreneurship fellowship in his name. Former Bank of America and World Bank chief A.W. “Tom” Clausen, a longtime Berkeley-Haas benefactor, passed away Monday from complications from pneumonia, according to media reports. He was 89.

Former Bank of America and World Bank chief A.W. “Tom” Clausen, a longtime Berkeley-Haas benefactor, passed away Monday from complications from pneumonia, according to media reports. He was 89. Professor Emeritus Michael Conant, a Haas faculty member for more than three decades whose research spanned the fields of law and economics, passed away at his Kensington home Dec. 7. He was 88 years old.

Professor Emeritus Michael Conant, a Haas faculty member for more than three decades whose research spanned the fields of law and economics, passed away at his Kensington home Dec. 7. He was 88 years old. Peter Kontes, MBA 74, principal of Greenwich Advisory Group and co-founder and former CEO of Marakon Associates, has passed away at the age of 65.

Peter Kontes, MBA 74, principal of Greenwich Advisory Group and co-founder and former CEO of Marakon Associates, has passed away at the age of 65.