“Classified” is a series spotlighting some of the more powerful lessons faculty are teaching in Haas classrooms.

Sahar Yousef stood before a packed room in Connie & Kevin Chou Hall in early March and recited some grim statistics. Productivity growth in the U.S. has been stagnant for nearly 15 years. The average knowledge worker gets interrupted every 90 seconds. Seventy-six percent of workers say they feel chronically drained by day’s end, and 96% percent of senior business leaders are on the verge of burnout.

The fact is that despite an abundance of technology to make us more productive, we’re still up against the limitations of human biology, Yousef said.

“We have at our disposal all of this amazing modern technology—Slack and Gmail and smartphones—and yet we’re trying to use these new tools with ancient technology: the human brain and the human body,” said Yousef, a cognitive neuroscientist and member of the Berkeley-Haas professional faculty. “There are fundamental biological laws that we are bound to, but we fight them instead of pausing to understand how to make these old and new technologies work together.”

There are fundamental biological laws that we are bound to, but we fight them instead of pausing to understand how to make these old and new technologies work together. —Sahar Yousef

The evening & weekend MBA students who had signed up for her class, “Becoming Superhuman: The Science of Productivity and Performance,” were more than ready to take that pause. It was the second time the elective had been offered, and it was once again oversubscribed. On the first day of class, each of the 50 students received a binder with findings from a pre-assessment that measured—among many other things—their ability to focus, how well they prioritize, and their risk of burnout. They learned, too, about their genetically determined sleep-wake cycles, and how their results compared to their peers.

Then, over the course of four Sunday afternoons, Yousef and co-lecturer Lucas Miller helped students learn about and implement research-based strategies for working more efficiently and effectively. (The course moved online after the first session, when the spreading coronavirus pandemic forced the cancellation of in-person classes.)

Focus sprints and the science of habit formation

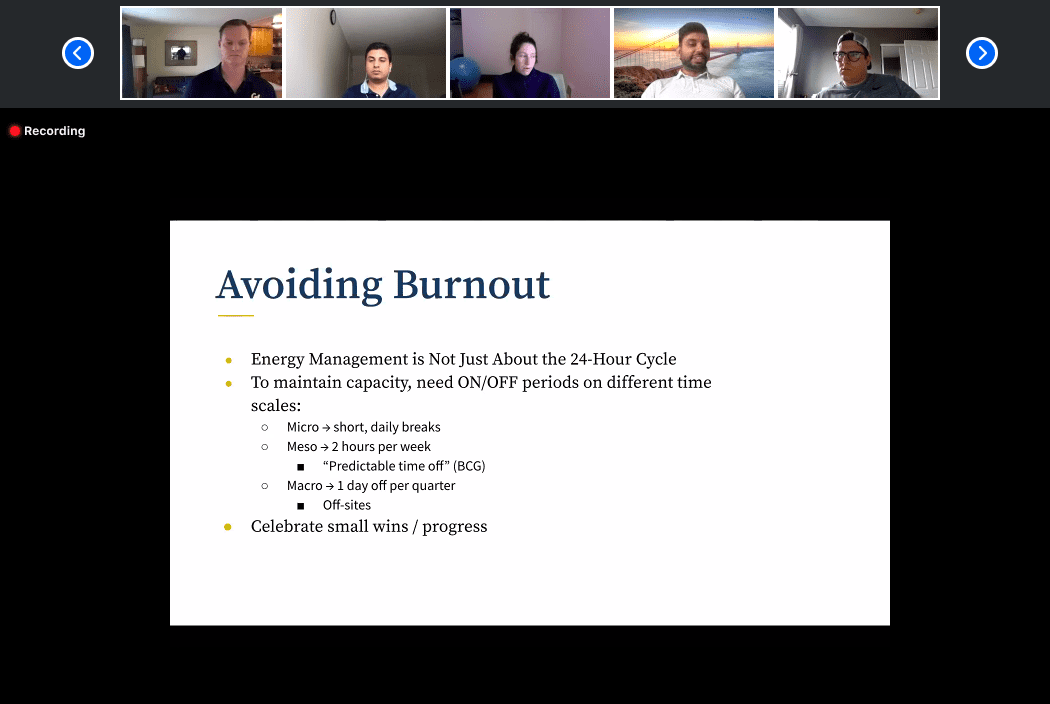

Students discovered how to structure their workdays to take advantage of times when their minds are most alert. They practiced “focus sprints”—50-minute stretches of defined work free from distractions (both visual and auditory). They each completed a deathbed exercise to identify life goals and how to stay on track to achieve them. They learned about research finding that meditation changes the physical structure of the brain, increasing cortical thickness and potentially slowing cognitive decline over time. They discovered, too, the science behind new habit formation.

The insights were at times surprising. A 2017 study, for example, found that if someone can see a smartphone nearby—even if it’s not her own and even if it’s turned off—their cognitive performance will suffer. People intuitively know from looking at someone whether they are sleep deprived, and are more likely to think they are not trustworthy or smart. Bedrooms should be kept at about 65 degrees for optimal sleep (especially for men).

When the students completed an assessment at the end of the class, the results showed that as a group, they improved across key measures of performance and productivity, including a greater ability to focus and manage priorities. While 86% of students reported that they used to check their phones throughout the day “just to check it”, only 30% of them reported doing so by the time the course ended. They reported their uninterrupted focus time increased more than 50%, from 85 minutes to 135 minutes. Nearly every student said they now accomplish their top priorities for the day, compared to only a third of students at the beginning of the course.

Mailynh Phan, EWMBA 21 and the CEO of Napa-based RD winery, signed up for the course after feeling overwhelmed by distractions and not finishing what she set out to do each day. Now, she said, “I understand how my biology works and how I can harness it to my advantage.”

Defining peak performance

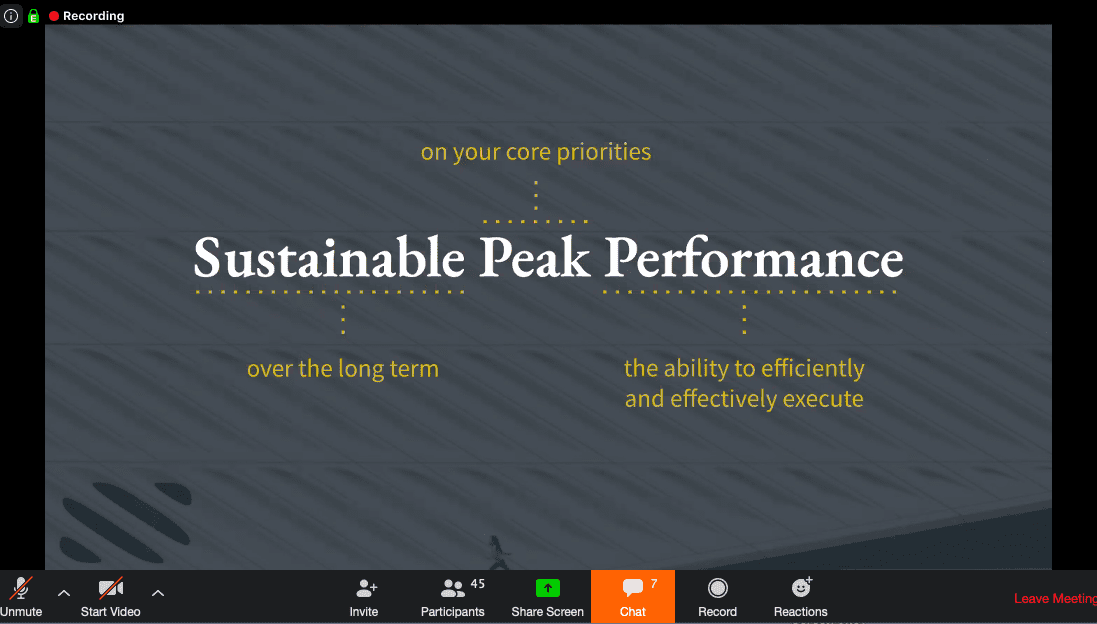

One of the challenges that Yousef and Miller faced in designing the course was definitional. The course is fundamentally about a concept they call “sustainable peak performance,” but they understood that, in practice, it would mean different things to different people.

“Productivity and performance are intrinsically vague concepts,” said Miller. “For a sales person, greater productivity could mean they’re having more or better customer conversations. To an engineer, it could mean ‘Don’t interrupt me, no meetings.’ To a parent it could mean ‘I just want my kids to leave me alone for an hour.’”

For this reason, sessions were broken up into specific themes, with differing time scales. This meant the first class was devoted to the 24-hour cycle and how students, through focus sprints and other methods, could better use their brains and bodies to get more done in fewer hours. The second class session was about performing at peak levels, and the idea that working faster and with more focus doesn’t mean much if the effort is not directed toward top priorities or goals that are personally meaningful. The third meeting centered on the science of aging and lasting habit formation. The final session was about integrating course concepts into work teams and managing and developing other people.

Everything Yousef and Miller taught was grounded in applied science. “I can’t imagine a course about how to work and live more efficiently and effectively without data to back it up,” said Yousef. “Otherwise it’s just a Tony Robbins event.”

I can’t imagine a course about how to work and live more efficiently and effectively without data to back it up—otherwise it’s just a Tony Robbins event. —Sahar Yousef

“Life-changing” strategies & insights

When asked about the course, students used words like “life-changing” and “gamechanger.” Learning about the science behind performance and productivity was crucial to their understanding, they said, along with the course’s focus on practical strategies that were instantly adaptable to their lives.

For Beverly Correa, the sudden shift in March to working from home because of the pandemic proved to be extremely challenging. “By the time the first Friday rolled around, I thought to myself ‘There is no way I’m going to last if I have to do this for two or three months,’” said the J.P. Morgan vice president.

In response, she devised a work schedule that better aligned with her sleep-wake cycle, or chronotype. She had always thought of herself as a morning person, but getting confirmation that she is genetically “AM-shifted” has inspired her to tackle her demanding work earlier in the day. She saves afternoons, when she knows her productivity is likely to ebb, for focus sprints or more routine tasks. Now, she’s meditating and making sure she’s staying hydrated. When it comes to forming new habits, she cuts herself a break: she knows that trying to develop too many at once won’t work.

Correa credits the course with not only keeping her on track during the crisis, but also giving her tools for the long run.

“I don’t know if I’d call myself ‘superhuman’—that seems like a really high bar—but I’m definitely more productive and more intentional about my work and my life,” said Correa, who graduated from the Berkeley-Columbia Executive MBA program in 2013 and was one of 15 alumni who audited the course (out of a record 75 who applied for spots).

I don’t know if I’d call myself ‘superhuman’—that seems like a really high bar—but I’m definitely more productive and more intentional about my work and my life. —Beverly Correa, BCEMBA 13

Prabhat Dhar, EWMBA 20, re-evaluated his career after taking the class and realizing he wanted to do more to help people in their everyday lives. He recently left his job at a healthcare marketing startup to lead business development at Headspace Health, a unit of the mindfulness and meditation platform provider.

Dhar said the class not only exemplifies the Haas Defining Leadership Principle of Students Always, but also reminds him of why he chose Haas in the first place.

“Haas isn’t just about creating great business leaders and great managers,” he said. “Haas also recognizes the human element and reminds us that we are all on this path as unique individuals, but also together. This class really embodies that spirit.”

With 5% of the world’s population and 25% of its prisoners, the United States is the most punitive country in the world. Among developed countries, the disparities are even more striking: The U.S. relies on incarceration for 70% of criminal sanctions, while in Germany, it’s 6%.

With 5% of the world’s population and 25% of its prisoners, the United States is the most punitive country in the world. Among developed countries, the disparities are even more striking: The U.S. relies on incarceration for 70% of criminal sanctions, while in Germany, it’s 6%.