Shortly before Layshia Clarendon, BA 13 (American studies), was drafted into the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA), the Cal senior attended a pre-draft orientation. Clarendon raised a hand and inquired about matching 401(k)s. The people fielding questions were floored. They weren’t used to college students knowing what a 401(k) was, let alone being savvy enough to ask about matching contributions.

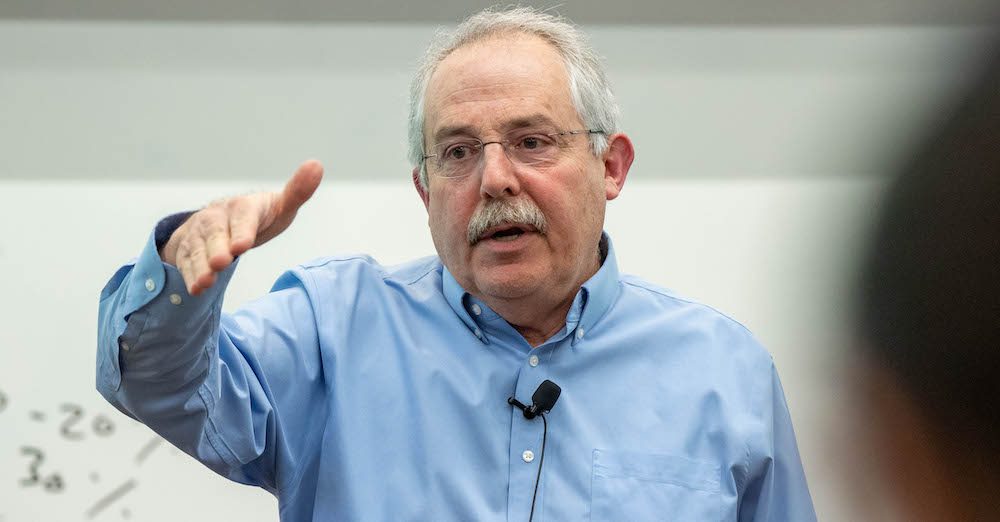

“I remember going to that meeting and thinking, ‘Oh, wow, I already know some of this,’” Clarendon recalls. When it came to financial literacy, Clarendon was miles ahead of most of their peers—all thanks to an independent study course they’d taken with Haas professional faculty member Stephen Etter, BS 83, MBA 89, called Financial & Business Literacy for the Professional Athlete.

For more than 20 years, Etter has helped scores of UC Berkeley athletes prepare for the financial realities of turning pro. Everyone from football great Marshawn Lynch and quarterback Jared Goff to Olympic swimmer Missy Franklin and golf phenom Collin Morikawa, BS 19, have learned about navigating contracts, choosing advisors, budgeting, investing, and more for their lives post-graduation.

Now, all of these issues are relevant for students too. In 2019, legislation was passed—first in California, then later throughout the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA)—allowing college athletes to earn compensation for the use of their name, image, and likeness (NIL) via sponsorships. No longer are questions about agents, contracts, and taxes part of a hypothetical future; student-athletes are facing them today, intensifying the need for Etter’s class.

“I’m working with students who are putting a half to three-quarters of a million dollars in their pocket today,” Etter says. The trouble was that his independent study only reached a small number of students. This coming fall, with the help of a grant from Robinhood Money Drills, Etter is expanding his course and bringing it to many more UC Berkeley student-athletes.

Mary Elizabeth Taylor, vice president of international government and external affairs for Robinhood Markets, Inc., says one of the company’s top priorities is providing the next generation with access to financial education. “Through the Robinhood Money Drills program, we are proud to give college students and student-athletes a strong foundation to responsibly manage their finances for the future,” she says. UC Berkeley is one of eight schools nationwide benefitting from the initiative.

It’s how much you keep

The idea for an independent study for athletes first occurred to Etter when one of his students, Nnamdi Asomugha, BA 06 (interdisciplinary studies), approached him for some advice. Asomugha was preparing for the draft (ultimately a first-round draft pick by the Oakland Raiders) and was suddenly facing major decisions that would affect his economic future. Etter, one of the founding partners of Greyrock Capital Group, had been teaching corporate finance at Haas for nearly a decade by then. He favored experiential learning with real-world application, and helping athletes navigate the complex waters of a professional career more than fit the bill.

Athletes turning pro find themselves in an unusual position, entering highly lucrative careers while having no financial training. The eye-popping mega-salaries that generate headlines are not the norm in pro sports, but starting salaries for many athletes are nevertheless substantial. Still, as former National Football League (NFL) player Justin Forsett, BA 14 (interdisciplinary studies), put it, “It’s not how much you make, it’s how much you keep.”

Forsett, who played pro football for nine years and is now an entrepreneur and motivational speaker, says taking Etter’s course gave him a real advantage. “There weren’t a lot of courses on financial literacy when I was a kid, in high school, or even in college,” he says. After gaining a solid foundation with Etter, he entered the NFL with what he calls “a conservative approach.” He explains, “I wasn’t going out getting fancy new cars. I knew it was about how much I could actually keep and save and invest in the right things.”

Keeping your future self in mind

Each year, Etter begins the class by sharing a series of sobering statistics: 78% of retired NFL players suffer financial hardship. Nearly 16% of NFL players have filed for bankruptcy. And 60% of former National Basketball Association (NBA) players are broke. These brief, cautionary tales drive home a crucial point that’s easily overlooked by young student-athletes: While the pros earn big salaries during their careers, those careers are often short and can be wildly unpredictable.

“Steve tells us the reality,” says Cam Bynum, BA 20 (American studies), who studied with Etter and just finished his third season as a safety with the Minnesota Vikings. “The average lifespan in the NFL is three years,” he says. “If you’re blessed, you’ll make it to 10 years, maybe 12. So that means you’re retiring at 32 years old, maybe 35. That’s just half your life. So then, what are you going to do?” Without Etter to prompt them, many student-athletes might never give that question much thought.

Elijah Hicks, BA 20 (American studies), a safety for the Chicago Bears, says that one of the most valuable aspects of the course was that it forced him to think ahead. “I got to put myself in my future self’s shoes,” he says. “The class puts you in scenarios before you’re actually there, so now, I’m more prepared and I’m not surprised by anything that pops up, like taxes.” High-earning athletes, for instance, not only have to pay taxes in their home state but in nearly every state they play in, a fact that shocked many of Hicks’ first-year teammates—but not him. Etter also helped Hicks start a nonprofit, Intercept Poverty Foundation, to provide emergency grants to low-income UC Berkeley students during the pandemic.

Learning to ask the right questions

Since the course’s inception, athletes from a range of sports have studied with Etter, players heading to the NFL, NBA, WNBA, and Major League Baseball (MLB), along with swimmers, golfers, and water polo players. News of the class has tended to spread by word of mouth among teammates and friends, but Etter says coaches, too, have been instrumental in steering students to his door. “The Cal coaches have had the insight and caring attitude to make sure they prepared their athletes for the financial aspects of their careers,” he says.

Not all professional careers are the same, however. Swimmer and six-time Olympic medalist Ryan Murphy, BS 17, knew he wanted to swim professionally after his success at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics, but he didn’t know what that entailed. In Etter’s class, Murphy’s fellow students that semester were heading for the NFL, but as a swimmer, Murphy’s professional path was less straightforward. “Our earning power is completely based on marketing,” he says. So Etter tailored the learning, helping him focus on finding a marketing agent.

“He connected me with people on campus and had me sit down for meetings with them,” Murphy recalls. Etter also encouraged him to talk to older swimmers who’d turned professional. “He was kind of a master connector for me.”

Getting out and talking to people is a big part of what Etter teaches. Whether it’s picking an agent, a financial advisor, or an insurance broker, knowing the kinds of questions to ask to make decisions that are in their own best interest is a fundamental skill he wants these athletes to learn. Sometimes, those questions come back to Etter himself. He continues to serve as a mentor to his student-athletes—they all have his number and aren’t shy about texting or calling for advice.

Changing the playing field for college athletes

Similar to professionals, NIL allows college athletes to engage in sponsorships and receive cash payments and gifts. For example, student-athletes may enter contracts to appear for autograph signings, endorse products via social media, conduct camps and clinics, post personalized video greetings, and more. However, the policy precludes students from entering pay-for-play contracts with colleges and universities.

Some Cal athletes secure deals on their own or through agents, while others are paid through the California Legends Collective, a newly formed organization (not affiliated with UC Berkeley) funded by donors who, together, create income opportunities like those mentioned above for Cal student-athletes. Advisory Board members include Lynch, Clarendon, and Murphy.

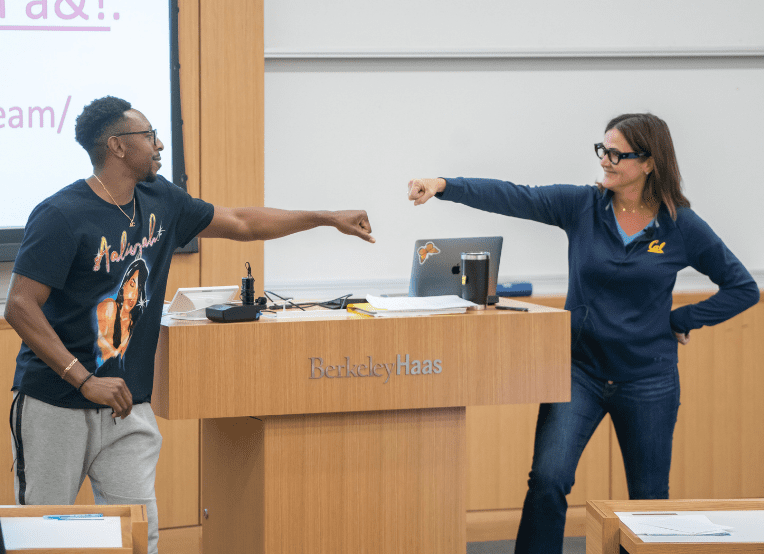

Christian Trigg, MBA 23, director of brand development for the Cal women’s basketball program, says the new NIL rules benefit players and the team as a whole. “This is a huge opportunity for students to start building wealth at an earlier age,” he says. “Especially athletes who might be first-generation college students.” In his newly created position, Trigg will help members of the team build their brands and secure NIL sponsorships, which in turn will help attract talented recruits to Cal. As women’s basketball coach Charmin Smith notes, “Having a strong NIL presence is critical in today’s college athletics environment.”

Cal football player Jaydn Ott is one of the students who’s benefited from Etter’s class while still at Cal. Ott, a running back with a likely future in the NFL, has begun earning money through NIL contracts, and he’s clear-eyed about the importance of financial literacy. “I want to understand what’s going on with my money when I speak to my financial advisors, so I’m not just giving somebody my money and saying, ‘Here, do whatever,’” he says. “I’m able to sit down and talk with them and understand what’s actually going on.”

“I want to understand what’s going on with my money when I speak to my financial advisors, so I’m not just giving somebody my money and saying, ‘Here, do whatever.’ ” – Jaydn Ott, Cal running back.

Just like pros, college athletes need to understand the taxes they owe, and Etter makes sure his students do. “A lot of NCAA athletes don’t understand the difference in income and taxes between being a W-2 employee and a 1099 contractor,” he says. NIL compensation is entirely 1099, which means there is no tax withholding; players must pay estimated taxes. Etter suspects that more than a few student-athletes across the country will inadvertently fail to pay sufficient taxes. But Ott won’t be one of them. “After Jaydn got his first paycheck,” Etter says, “he put half away for taxes. And then he was worried, so he put half of the other half away for taxes, too.”

Spreading the wealth

Etter, who has three times won the school’s prestigious Earl F. Cheit Award for Teaching Excellence from his undergraduate students (once as a graduate student instructor), has long wanted to empower more students with the skills he teaches. Now, thanks to the grant from Robinhood, he’s going to. Starting this fall, the course will be reclassified as a full-fledged class rather than an independent study, which will allow more student-athletes to take it. The structure of the course is being retrofitted to accommodate up to 250 students while maintaining the active learning style that’s a hallmark of the class. Etter will be assisted by MBA graduate student instructors who are reflective of the diverse student-athlete population.

The money is helping Etter fulfill a long-held goal. “My dream,” he says, “was to get this grant and to educate all 1,000 student-athletes at Cal.” From there, he says he’d like to bring the class to all NCAA athletes and ultimately to all 55,000 students on the Berkeley campus.

Over the next few years, as the cultural conversation around women at work gathered momentum, companies started asking McElhaney for more proof of a bottom-line payoff to hiring women.

Over the next few years, as the cultural conversation around women at work gathered momentum, companies started asking McElhaney for more proof of a bottom-line payoff to hiring women.

MBA students enrolled in the Social Impact Metrics course at Haas spent the fall semester wrestling with a challenge that’s puzzled management experts for decades: How do you go about measuring the effectiveness of a nonprofit program?

MBA students enrolled in the Social Impact Metrics course at Haas spent the fall semester wrestling with a challenge that’s puzzled management experts for decades: How do you go about measuring the effectiveness of a nonprofit program?