Nine new assistant professors have joined the Haas School of Business faculty this year, with cutting-edge research interests that range from illicit supply chains to unequal social hierarchies; from financial crises to the incentives that shape innovation; and from health care management to decentralized finance to marketing and the demand for firearms.

The nine tenure-track hires are the result of a concerted effort by Dean Ann E. Harrison and other Haas leaders to expand and diversify the faculty.

“We are thrilled to welcome this wonderful, diverse new group of academic superstars to Berkeley Haas,” says Dean Ann E. Harrison. “We clearly are bringing the best to Haas, increasing the depth and breadth of our world-renowned faculty, and reinforcing our place among the world’s best business schools.”

The new faculty members have hometowns throughout the U.S. and around the world, including Texas, New York, Massachusetts, and Illinois; Iran, the Dominican Republic, China, and the Netherlands. Seven of them are women; one is Black, and one is Latinx.

“This is our most diverse cohort of new faculty ever, each one a rock star in their own right,” says Jennifer Chatman, Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and the Paul J. Cortese Distinguished Professor of Management. “We are very proud that we were able to lure them to Berkeley Haas.”

The new faculty members start on July 1, with most beginning to teach in spring 2023. They bring the total size of the ladder faculty to 88, up from 78 in 2020-2021.

Meet the faculty

Assistant Professor Matthew Backus, Economic Analysis & Policy

(he/him)

Hometown: Chicago, Ill.

Education:

PhD, Economics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

MA, Economics, University of Toronto

BA, Economics and Philosophy, American University

Research focus: Industrial organization

Introduction: I’m an economist with broad interests. Most recently, I’m interested in how we can use the tools developed by the industrial organization community to understand inequality and the distributional effects of policy.

Teaching: Microeconomics and Antitrust Economics (MBA)

Most excited about: After spending a year visiting, I’m most excited about the economics community at Berkeley.

Fun fact: I have a border collie, who is in training as a herding dog.

Assistant Professor Sa-kiera (Kiera) Tiarra Jolynn Hudson, Management of Organizations

(she/her)

Hometown: Albany, NY

Education:

PhD/MA, Social Psychology, Harvard University

BA, Psychology and Biology, Williams College

Research focus: I study the psychological processes involved in the formation, maintenance, and intersections of unequal social hierarchies, with a focus on empathic/spiteful emotions, stereotypes, and legitimizing myths.

Introduction: I am a social psychologist by training, focusing on the nature of intergroup relations as dominance and power hierarchies. I have studied several psychological processes, including the role of legitimizing myths in justifying unequal societal conditions, the role of group stereotypes in the experience and perception of prejudice, and the role of empathic and spiteful emotions in supporting intergroup harm. My work is multidisciplinary, incorporating quantitative as well as qualitative methods from various disciplines such as political science, sociology, and public policy.

I am a fierce advocate for building community, providing mentorship, and supporting authentic inclusion for everyone. I believe it is a moral imperative to be present as a vocal, queer-identified Black women in academe, given the lack of representation, and I’m excited to see how I can contribute to diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts at Haas.

Teaching: Core Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (MBA)

Most excited about: I identify UC Berkeley as my intellectual birthplace. It was during a summer internship program through the psychology department in 2010 where I first became interested in studying power structures and intergroup relations simultaneously. My overall research interests haven’t changed since that fateful summer. Being a faculty member here is truly a dream come true!

Fun fact: I love organizing and planning, so much so I taught myself how to use Adobe InDesign to create my own planner. I am also an avid foodie and cannot wait to check out the Bay’s food and wine scenes.

Assistant Professor Ali Kakhbod, Finance

(he/him)

Hometown: Isfahan, Iran

Education:

PhD, Economics, MIT

PhD, Electrical Engineering & Computer Science (EECS), University of Michigan

Research focus: Information frictions; liquidity; market microstructure; big data; and contracts

Introduction: I am a financial economist with research interests in financial intermediation, liquidity, contracts, big (alternative) data, banking and financial crises. A common theme of my research agenda is to study various informational settings and their financial and economic implications. For example: When does securitization lead to a financial crisis? Why is there heterogeneity in the means of providing advice in corporate governance? How does information disclosure in OTC (over-the-count) markets affect market efficiency? My research has both theory and empirical components with policy implications.

Teaching: Deep Learning in Finance (MFE)

Most excited about: Berkeley Haas is the heart of what’s next with world-class faculty working on exciting and innovative research. Given that my interdisciplinary research interests span finance, economics and big data issues, I could not ask for a better fit.

Fun fact: In my free time, I like to ski, sail, hike, and enjoy the outdoors.

Assistant Professor Ambar La Forgia, Management of Organizations

(she/her)

Hometown: I was born in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, but I grew up in Washington, DC and São Paulo, Brazil.

Education:

PhD, Applied Economics and Managerial Science, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

BA, Economics and Mathematics, Swarthmore College

Research focus: Health care management; mergers and acquisitions; firm performance

Introduction: My research studies the relationship between organizational and managerial strategies and performance outcomes in the health care sector. In particular, I use quantitative methods to study how the strategic decisions of corporations to merge, acquire, or partner with other organizations can change managerial processes in ways that impact both financial and clinical performance. A secondary research strand studies how health care organizations adapt their service delivery and prices following changes in state and federal legislation.

Before joining UC Berkeley, I was an assistant professor of health policy and management at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. I am excited to continue to explore issues of healthcare quality, equity, and cost, while digging deeper into the management practices and organizational structures that could influence these outcomes.

Teaching: Leading People (EWMBA)

Most excited about: It is an honor to join the world-class faculty at Haas, and I am so excited to learn from and collaborate with my MORs colleagues on both the macro and micro side. Since my research is interdisciplinary, I also look forward to connecting with scholars in the School of Public Health.

As a self-proclaimed “city girl,” I am excited to get out of my comfort zone and explore the natural beauty of Northern California.

Fun fact: My hobbies include yoga, urban gardening, adopting animals and stand-up comedy.

Assistant Professor Sarah Moshary, Marketing

(she/her)

Hometown: New York City, NY

Education:

Phd, Economics, MIT

AB, Economics, Harvard College

Research focus: Marketing and industrial organization

Introduction: My research interests span quantitative marketing, industrial organization, and political economy. I am currently working on projects related to paid search advertising, the pink tax (price gap in products targeted to women), and the demand for firearms. Before joining Haas, I worked at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and at the University of Pennsylvania.

Teaching: Pricing (MBA)

Most excited about: I am excited to get to know my future colleagues!

Fun fact: My two hobbies are running and pottery—though I am more enthusiastic than talented at either :).

Assistant Professor Tanya Paul, Accounting

(she/her)

Hometown: Murphy, Texas

Education:

PhD, Accounting, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

BS, Economics, Statistics and Finance, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

Research focus: Standard-setting and financial reporting; the determinants and consequences of voluntary disclosures

Introduction: After getting my PhD, I spent a year at the Financial Accounting Standards Board learning about contemporary accounting issues and understanding the types of questions that standard setters are grappling with. I hope to continue working on research that is helpful to standard setters in coming up with standards that ultimately improve financial reporting.

Teaching: Corporate Financial Reporting (MBA)

Most excited about: I love how interconnected the area groups are within Haas. There are so many potential learning opportunities, especially for a newly minted researcher like me.

Fun fact: In my free time, I love to read and play the piano—I had learned it as a child and am trying to relearn it now as an adult.

Assistant Professor Carolyn Stein, Economic Analysis & Policy

(she/her)

Hometown: Lexington, Mass.

Education:

PhD, Economics, MIT

AB, Applied Mathematics and Economics, Harvard College

Research focus: Economics of science, innovation, and applied microeconomics

Introduction: I study the economics of science and innovation. My research combines data and economic theory to understand the incentives that scientists face and decisions that they make, and how this in turn shapes the production of new knowledge.

One thing I love about economics is that it’s less of a narrow subject area, and more a set of tools and principles that apply to a stunningly wide array of topics. I’m excited to work with Haas students to help them understand how economic principles can improve their decision-making, both in their careers and in other areas of their lives—maybe even in ways that surprise them!

Teaching: Microeconomics (EWMBA)

Most excited about: I’m excited to be part of a large and superb applied microeconomics community—at Haas, and more broadly at Berkeley as a whole.

Fun fact: I am an avid cyclist and skier, and I was on the cycling team at MIT. Since moving to the Bay Area, I’ve loved the hills and mountains in the area. I’m working on taking my riding off road (gravel and mountain biking) and skiing off-piste (backcountry).

Assistant Professor Sytkse Wijnsma, Operations and IT Management

(she/her)

Hometown: Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Education:

PhD, Management Science and Operations, Judge Business School, University of Cambridge

MPhil, Management Science and Operations, Judge Business School, University of Cambridge

BSc & MSc, Economics and Finance, VU University, Amsterdam

Research focus: My primary research interest is designing supply chain and policy interventions that help solve real-world challenges with social and environmental impact.

Introduction: I am very excited about my projects on illicit supply chains and how they undermine social and environmental goals. The context of these projects spans a wide range of areas, from illicit waste management to illegal deforestation. I am also excited to deepen and expand ongoing research collaborations with governments and industry to investigate these issues.

Teaching: Sustainability in Business (Undergraduate)

Most excited about: Many things! Berkeley Haas, being at the forefront of sustainability, has a unique position that combines the same ideals that drive my research with opportunities for collaborative research with serious impact. The amazing colleagues and close connections to industry make it even more exciting to join this community!

Fun fact: My first and last name originate from Fryslân, a northern province in the Netherlands, where it is still tradition to name your children after family members. So although my name is quite rare in the rest of the world, in our family it crops up in every generation!

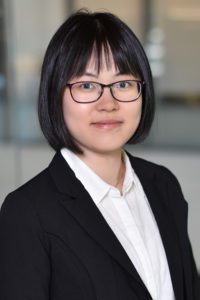

Assistant Professor Valerie Zhang, Accounting

(she/her)

Hometown: Shanghai, China

Education:

PhD, Northwestern Kellogg School of Management

MA, Economics, University of Toronto

BCom, Finance and Economics, University of Toronto

Research focus: Information dissemination; information cascades on social media; retail investor behavior; decentralized finance

Introduction: I am passionate about doing research or working on personal projects that can express my creativity. I enjoy merging disjointed ideas and working on interdisciplinary research. My dissertation combines two literatures: one in computer science on information cascades on social media, and another in finance and accounting on the effects of disseminating financial news. I am also very curious about emerging technologies that are reshaping the financial industry. Since I work on areas that are new to the research community, I sometimes feel like a lone traveler exploring completely new territories. It is terrifying but also extremely rewarding!

Teaching: Financial Accounting (Undergraduate)

Most excited about: I look forward to inspiring my students to be entrepreneurial and to come up with creative business ideas or projects.

Fun fact/hobby: I write short stories. The one I am working on has an alien and a squirrel in it.