Topic: Healthcare

Paul Gertler takes IBSI leadership baton from founder Laura Tyson

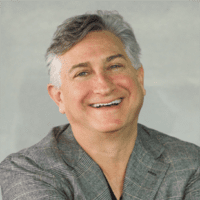

Berkeley Haas Prof. Paul Gertler, an international expert on evaluating programs to fight poverty, improve health care and outcomes, expand financial inclusion, and support early childhood development, has been appointed as faculty director of the Institute for Business and Social Impact (IBSI) as of July 1.

Gertler takes the leadership baton from IBSI Founding Director and Former Dean Laura Tyson, who launched the institute in 2013 to serve as both a central hub and a catalyst for expanding the school’s social impact programs. Tyson will retain her role at Haas as a professor of the graduate school and will be based out of the Blum Center for Developing Economies, where she chairs the board of trustees.

“Over the past seven years, IBSI has secured the reputation of Berkeley Haas as a leader among top-ranked business schools in the social impact space, and helped hundreds of Haas and Cal students launch careers focused on addressing social and environmental challenges,” Tyson said. “I’m thrilled to leave the institute in the capable hands of Professor Paul Gertler, who brings extraordinary research, expertise, and engagement on developing and implementing programs that fight poverty and improve public health and education outcomes around the world.”

Gertler said he plans to build on Tyson’s work by expanding the generation and use of scientific evidence to better understand the social impact of business decisions.

“Laura has always championed the purpose of business beyond shareholder value: that business decisions affect workers’ lives, customers’ lives, and the environment, and create culture norms that affect diversity and inclusion. She has also challenged the prevailing wisdom of business schools in championing a ‘shareholder lens,’ and it seems much of the establishment is now catching up to her,” Gertler said. “I hope to move that mission forward in this time of great upheaval.”

Gertler is the Li Ka Shing Professor of Economics at Haas and scientific director for the Center for Effective Global Action. He’s an expert on impact evaluation, acting as principal investigator on large, multisite evaluations of programs to fight poverty and improve healthcare in Mexico, Rwanda, and around the world. He also served as the chief economist of the Human Development Network of the World Bank from 2004 to 2007. His recent research has focused on topics as diverse as how vocational training has helped women but left men behind; the relationship between childhood sugar consumption and obesity; and air conditioning and climate change. He has been a member of the Haas faculty since 1996, and holds a PhD in economics from the University of Wisconsin.

(Tyson) has also challenged the prevailing wisdom of business schools in championing a ‘shareholder lens,’ and it seems much of the establishment is now catching up to her.” —Paul Gertler

Since its founding, IBSI has grown from four centers and programs to six. It now includes the Center for Responsible Business, the Center for Equity, Center and Leadership (EGAL), the Berkeley Blockchain Initiative, and the Sustainable and Impact Finance Program (SAIF). The institute houses two pre-college programs for high school and middle school students, Boost and the Berkeley Business Academy for Youth (BBAY). IBSI will expand during this academic year, adding the Gilbert Center for Health Economics. There will also be work to establish a center related to financial innovation, regulation and inclusion, Gertler said.

As an influential economist with a vast network, Tyson’s leadership has been instrumental in building IBSI. She helped raise the funds to launch EGAL and secured funding for SAIF, which she launched last fall with Assoc. Prof. Adair Morse to drive research, education, and leadership in the growing field of sustainable and impact finance. Tyson worked with former Dean Rich Lyons to win the five-year partnership with Ripple as a partner in the University Blockchain Research Initiative to accelerate research and develop leaders in the area.

Tyson also built a financial inclusion research partnership with the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth. Other IBSI initiatives include the Jacobs Foundations Fellows, supporting full-time MBA students, the Social Impact Fellows, and a series of 26 IBSI Case Studies. IBSI’s affiliated faculty offer 29 courses in Berkeley Haas degree programs.

On a Zoom call last week with faculty, staff, and Haas leaders thanking Tyson for her service, IBSI Executive Director Cathy Garza commented on Tyson’s “students always” attitude. “She is ever-curious, absorbing the blockchain landscape, studying AI and the future of work in Germany, and delving into sustainable finance,” Garza said. “She’s always passionate about women’s economic empowerment, having co-authored the first ever UN high-level panel report on the topic.”

That holds on a personal level as well.

“As a leader, Laura is visionary, strategic, and thoughtful, bringing talent to bear on some of the thorniest problems of this generation,” said Kristi Raube, who served as IBSI’s founding executive director. “Most importantly, Laura was an example to so many of us, of how to be a strong woman who leads with intelligence and from her heart.”

Most importantly, Laura was an example to so many of us, of how to be a strong woman who leads with intelligence and from her heart. —Kristi Raube

Federal officials turn to a new testing strategy as infections surge

Information can affect you like drugs, sugar, or money

How Twentyeight Health founder Amy Fan is making birth control accessible and affordable

Leaders of developing countries are particularly vulnerable during this pandemic

Answering viewer questions about workplace safety during the pandemic

MBA student helps raise millions for pop-up coronavirus testing lab

In early March, Peter Gallagher, EWMBA 22, was ushered into an emergency meeting headed by Prof. Jennifer Doudna, executive director of the Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI) and co-developer of the gene editing technology, CRISPR.

He and nearly 50 faculty, staff, students, and postdocs from the IGI were called upon to figure out how to repurpose their research labs to address the COVID-19 pandemic.

By the end of that meeting, Gallagher and the University Development and Alumni Relations fundraising team that supports the Institute had received marching orders to help raise $10 million to establish a pop-up coronavirus testing lab.

Raising that kind of capital can take months or even years to accomplish in normal times, Gallagher said. But surprisingly by the end of March, he and his colleagues had raised just over $10 million, enabling the Institute to build a diagnostic testing lab that can test 1,000 patient samples per day.

“It’s hard to overstate how hard that is to do in such a short amount of time,” Gallagher said. “In about three weeks’ time, the lab was up and running. It’s an incredible achievement.”

“I’ve never experienced anything like that,” he added. “But these are unprecedented times and people are responding in unprecedented ways.”

With the funding, IGI will be able to expand testing in the Bay Area, track the coronavirus, and support researchers focused on developing COVID-19 therapies, genome sequencing, and surveys to detect the prevalence of asymptomatic infections.

The coronavirus testing lab serves Berkeley students, first responders, homeless people, and people who are uninsured. Test samples come from local health agencies, including UC Berkeley’s Tang Center and Lifelong Medical Care.

Gallagher, an Oakland native and fifth-generation UC Berkeley student, has spent most of his career fundraising in the Northwest for social impact organizations, including his own, Seattle Catholic Worker, a Christian activist movement that focuses on serving the homeless and people living in poverty. So it’s no surprise that he was drawn to the Institute whose mission is to treat human diseases and end world hunger using genome engineering technologies like CRISPR.

“Peter has been instrumental in developing and maintaining our relationships with our donors, especially during the pandemic,” said Lucie Bardet, MBA 19, a project manager for the IGI. “His high emotional quotient and uncommon business intelligence has been a boon to the Institute.”

Bardet, who joined the Institute three months ago, has also been knee-deep in getting the lab up and running, she said. From supporting research teams tasked with handling diagnostic testing and vaccines to fundraising, Bardet, too, has been instrumental in helping the IGI quickly pivot to make the pop-up coronavirus testing lab become a reality.

Bardet said she’s enjoyed supporting COVID-19 relief efforts led by Jennifer Doudna. “For someone who has been working with startups and venture capitalists for the last few years, I’ve never seen a team respond this fast to a crisis.”

Gallagher and his coworkers will soon begin work on the second phase of fundraising for the pop-up COVID-19 lab, which he sees as a critical facility that will help slow the spread of the coronavirus and ultimately help people return to some semblance of normalcy, he said.

“While I can’t say that I’m leading this, I think we’ve all had to lead in different ways given the magnitude and scope of work,” said Gallagher. “The growth that I’ve had as a leader as a result of being at Haas has enabled me to respond more effectively to our work at this time.”

Expert Panel: How can we safely reopen the economy?

Returning society to some version of normal will require customized plans that may vary by locale, depending on the intensity of COVID-19 infections. Even so, the economy can’t be safely reopened without strong data, unified decision-making frameworks, and some policies that span the country.

That was the consensus of experts from the Haas School of Business and the School of Public Health who took part in a virtual discussion on reopening the economy Friday as part of the Berkeley Conversations COVID-19 series.

“One size does need to fit all for at least large swaths of the population,” said Assoc Prof. Jonathan Kolstad, a health economist with joint appointments at Berkeley Haas and the Department of Economics. “Everyone’s behavior affects everyone else. (Reopening) in the absence of any sort of coordination is an incredibly costly strategy.”

One size does need to fit all for at least large swaths of the population. —Assoc. Prof. Jonathan Kolstad

According to Maya Petersen, associate professor and co-chair of the Graduate Group in Biostatistics at the School of Public Health, fragmentation hurts the ability of any small population anywhere to respond effectively to their epidemics.

“Ideally what happens is you have a unified decision-making framework, you have unified communication, you have clear policies that span the country,’ Petersen said. “And within those, you have the ability to use your data locally to meaningfully fine-tune your epidemic response.”

If there was one steady drumbeat throughout Friday’s conversation it was data, data, data—which panelists agreed are a prerequisite for reopening, and which must be used to guide testing and identify outbreaks. Other key themes were putting proper systems into place, as well as restoring trust.

To do that, leaders need to be realistic, consistent, and deliberate, said Jennifer Chatman, professor of management and Associate Dean of Learning Strategies at Berkeley Haas. “The mental calculus of leadership is even more vital now because you need to anticipate how people are going to react to what you say and what you do,” Chatman said.

“The mental calculus of leadership is even more vital now because you need to anticipate how people are going to react to what you say and what you do.” —Prof. Jennifer Chatman

“Leaders should be realistic with their people—the future is going to be complicated, and it’s going to be challenging. At the same time, they also need to be reassuring, so people can continue to have some semblance of calm and be productive. Leaders need to ask people to comply with rules, but at the same time they need to call on people to use their ingenuity to address problems that we haven’t confronted before,” she said. “If there is any time that a deliberate leader was needed, now is the time.”

Prof. David Levine, a labor economist at Berkeley Haas, said the positive news is that all the tools of good management apply.

“For generations, we’ve been figuring out how to improve product quality, how to make food safer, or how to avoid environmental disasters. And the answer is good management,” he said. “There are lots of management tools around training, incentives, monitoring, and continuous improvement that we know how to use for lots of old threats. Coronavirus is a new threat, but the tools to fight it are the same tools.”

“There are lots of management tools around training, incentives, monitoring, and continuous improvement that we know how to use for lots of old threats. Coronavirus is a new threat but the tools to fight it are the same tools.” —Prof. David Levine

One key thing organizations must do is make it easy for employees to be safe. For example, it’s not enough to just tell people to wash hands: Managers must give people breaks to wash their hands. All states should require every workplace to complete an assessment to look for risks, as California does. Employees should have the authority to stop production if they see a health problem—right now, in most states, they don’t.

“Managers need to make clear that this is how you become a hero, and not a former employee,” Levine said.

However, if one large company has the wherewithal to implement safe solutions for their employees, but those employees live with people working at other firms that don’t, “it verges on futile for that large firm to do all those testing and safety strategies,” Kolstad commented. “At every point, coordination is critical from a health, economic and messaging perspective. If you’re a big employer across a lot of states, keeping your workforce healthy and safe is good for reopening, and good for your employees.”

People need to remember, however, that our goal as a society is not to get to zero transmissions: Unless we have a vaccine, the goal is to minimize the spread of the virus, Petersen said. The way to do that is to continue using public health techniques such as social distancing and hygiene, while employing integrated data streams to guide testing, identify outbreaks as early as possible, and quickly isolate any new cases.

“We all navigate risks in our lives every day. Thinking in terms of good public health principles, what you need to do is communicate risks clearly to people, have the data available to be able to quantify risks accurately, and you need to have people’s trust so when you say this is the best estimate of your current risk and this is what you need to do to mitigate it, people believe it,” she said.

We all navigate risks in our lives every day. Thinking in terms of good public health principles, what you need to do is communicate risks clearly to people, have the data available to be able to quantify risks accurately, and you need to have people’s trust so when you say this is the best estimate of your current risk and this is what you need to do to mitigate it, people believe it. —Assoc. Prof. Maya Petersen

That’s why organizations must tread carefully, Chatman said. “Crises like this one are opportunities for organizations to display their commitment. Employees are watching closely, and they’re going to remember what you did. If you are known as the employer who, when the going got tough, you got going, there will be long-term cultural consequences.”

This May 1 panel was sponsored by the Haas School of Business as part of Berkeley Conversations: COVID-19. This series of live, online events feature faculty experts from across the UC Berkeley campus who are sharing what they know, and what they are learning, about the pandemic. Panelists were Prof. Jennifer Chatman, Prof. David Levine, and Assoc. Prof. Jonathan Kolstad from Berkeley Haas and Assoc. Prof. Maya Petersen from the School of Public Health. The moderator was Assistant Vice Chancellor for Public Affairs Dan Mogulof.

Open-source smartphone database offers a new tool for tracking coronavirus exposure

Researchers from Berkeley Haas and four other universities have released a trove of smartphone tracking data in an open-source database—a powerful tool for studying how people are changing their movement patterns and potential exposure levels during the coronavirus pandemic.

The Covid-19 Exposure Indices, created by Berkeley Haas Asst. Prof. Victor Couture and researchers from Yale, Princeton, the University of Chicago, and the University of Pennsylvania in collaboration with location data company PlaceIQ, is aimed at academic investigators studying the spread of the pandemic. The data sets allow researchers to visualize how people can potentially be exposed to those infected with the virus, based on cell-phone movements to and from businesses and other locations where a great deal of the exposure happens.

Couture hopes that researchers may start to find correlations between the disease and certain venues and travel patterns. Looking forward, the data also could be useful in anticipating the movement patterns that predict where future outbreaks could reemerge once restrictions are lifted. “The end goal is to identify how changes in exposure rates within different types of venues and for different demographic groups impact the number of cases,” says Couture.

Couture and his collaborators are the first academics to release open-source smartphone location data. They are part of a much bigger movement of researchers, companies, and institutions making data easily and freely available to study the pandemic. For instance, Apple, Google, Foursquare, and other big companies have also released movement data. Couture hopes that by being transparent about their data source, methodology, and potential biases, they can make available data that is suitable for peer-reviewed research.

“We’re in the midst of an unprecedented sharing of data from the academic and technical communities,” Couture says. “We hope everyone can use this data to influence better policies during the coronavirus pandemic.“

We’re in the midst of an unprecedented sharing of data from the academic and technical communities. We hope everyone can use this data to influence better policies during the coronavirus pandemic.

The smartphones in our pockets are all equipped with GPS, and depending on privacy settings, many popular applications record our geolocation. Data providers buy and aggregate location information from different applications, and build databases that record the movement and visits to various venues for millions of devices.

Couture and his colleagues have so far released two indices derived from this smartphone movement data: the location exposure index (LEX), showing our movements between states and counties, such as people flying or driving across the country; and the device exposure index (DEX), showing how many people (as measured by their devices) we are coming into close proximity with outside the home. For instance, if you drive to Walmart and 100 other phones are at that same location, and then you drive to a drugstore with 50 people with phones inside before returning home, your DEX exposure level would be 150 people. More detailed data that includes types of venues (grocery stores, drugstores, big-box stores, parks) will be released soon.

An application of the data is shown below. This animated time-lapse map from January 23 to April 2 shows how people’s movements dropped much more quickly in some areas than in others, such as in the South and Southeast of the United States. This is represented by color changes from yellow to green to dark purple as the average device exposure within a county went down.

The data can’t tell researchers how well people are practicing social distancing at any given location, and therefore their specific risk of catching the coronavirus. But it can start to reveal how successful various policies—such as states of emergencies and shelter-in-place orders—have been. “When you prescribe rules of movement, when you tighten them, and when you relax them—you can correlate that with what people are actually doing and which groups and areas are reducing their exposure,” says Couture.

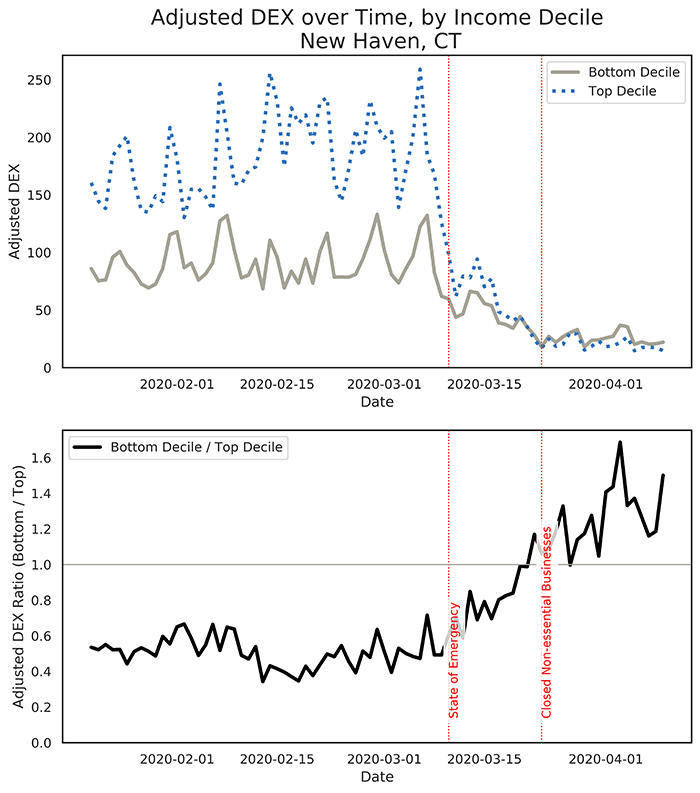

“It often looks like people start to reduce their exposure when a state of emergency is declared, but when the actual shelter in place order comes in, it has less impact on movement,” says Couture. An example is the analysis charted below for New Haven-Milford, Connecticut, which showed that the announcement of the state of emergency itself appeared to be a powerful mechanism that convinced people to reduce their movements, and hence their exposure, to the virus.

The exposure indices Couture and colleagues have compiled also include demographic information that can show which groups are at greater risk for exposure, such as minorities and low-income people. Exposure levels vary over time: The top chart in the set below shows that people living in New Haven, Connecticut neighborhoods with median incomes in the top 10% initially had higher exposure rates than those in the bottom 10%. After a state of emergency was declared, exposure levels in high-income neighborhoods declined much faster than in low-income neighborhoods. This may be because lower income people are more likely to work on the front lines in essential business, and have less ability to reduce their exposure than those who can afford to shelter at home.

The bottom panel shows the ratio of the device exposure index (DEX) for people living in neighborhoods with median income levels in the bottom 10% relative to those in the top 10%. A value higher than 1 signals that exposure is higher in low-income than in high-income neighborhoods

These patterns could prove helpful in showing which locations and demographics have the potential for greater exposure under different types of orders when policies have been gradually lifted.

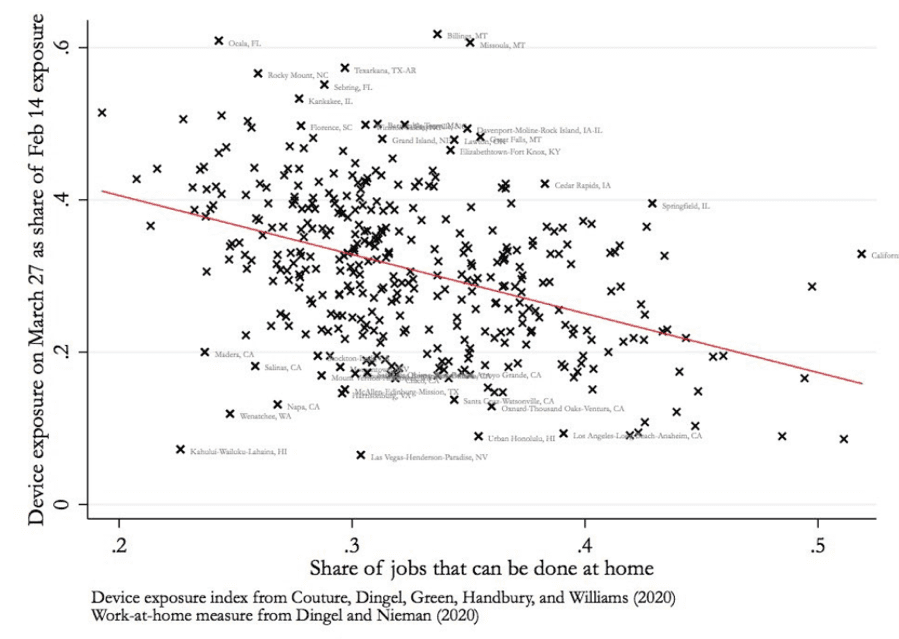

As another example, the graphic below shows that metropolitan areas with more jobs that can be done from home had larger reductions in potential exposure to the coronavirus. Again, this correlation suggests that who works from home depends on who can afford to do so while remaining gainfully employed.

Eventually, the explosion of location data has the potential to tease out even deeper stories explaining not just the hidden patterns behind our unique location in the world, but also the unexpected things that larger groups and types of places share in common. “One of the things we want to encourage is careful work to identify the causations behind these correlations,” says Couture.

The Covid-19 Exposure Indices were created by Jonathan Dingel of the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, Kevin Williams of the Yale School of Management, Jessie Handbury of the Unviersity of Pennsyania’s Wharton School of Business, Allison Green of Princeton University, and Victor Couture at Berkeley Haas.

Physician leader uses MBA skills to transform the patient-provider experience

Expert guide: Coronavirus impacts on business, the economy, and leadership

Berkeley Haas has a wide range of experts who can talk about how the coronavirus is impacting businesses and the economy, putting leaders to the test, and changing workplaces.

Need help finding the right expert? Contact our media relations team.

Economic Impact

David Levine

David Levine

Professor | Chair, Haas Economic Analysis and Policy Group

[email protected]

(925) 899-5938

Topics: Management practices in large corporations and multinationals, procedures and norms around behavior change and hygiene programs, impacts of high and low wages and of education in the business sector, labor economics, macroeconomics.

Laura D. Tyson

Distinguished Professor of the Graduate School | Faculty Director, Institute for Business & Social Impact

[email protected]

Assistant: Cynthia Okita [email protected]

Topics: Economic impact on global, U.S. and California economies; trade and competitiveness; jobs and disruption

James A. Wilcox

James A. Wilcox

Professor of Economic Analysis and Policy and Finance

[email protected]

(510) 642-2455

Topics: Macroeconomics and markets, recessions, Federal Reserve policy, business conditions, banking, consumer spending, unemployment and inflation

Severin Borenstein

Severin Borenstein

Professor, Economic Analysis and Policy | Faculty Director, Energy Institute at Haas

[email protected]

(510) 642-3689

Topics: Oil prices, energy markets, airline industry

Enrico Moretti

Enrico Moretti

Professor, Real Estate

[email protected]

510 642-6649

Topics: Urban economics, labor economics, economics of cities and regions, real estate

Kevin Coldiron

Kevin Coldiron

Lecturer, Finance

Topics: Stock market, finance

Jerome Dodson

Lecturer, Responsible Business

Topics: Stock market

Management, Leadership, Culture, Communication & Psychology

Jennifer Chatman

Jennifer Chatman

Professor of Management, Management of Organizations Group

[email protected]

(510) 642-4723

Topics: Organizational culture, crisis leadership, coronavirus impact on work and productivity, general management

Ellen Evers

Ellen Evers

Assistant Professor, Marketing

Topics: Influence of fear and other emotions on behavior, risk perceptions, risk communication, judgement and decision making

Don Moore

Don Moore

Professor, Management of Organizations

[email protected]

(510) 642-1059

Topics: Confidence and overconfidence regarding the course of the pandemic; remote work and productivity in self-quarantine; crisis leadership; managing people at a distance

Juliana Schroeder

Juliana Schroeder

Assistant Professor, Management of Organizations

[email protected]

510-664-9692

Topics: Differences between online and offline communication, judgment and decision making, interpersonal and intergroup processes

Dana Carney

Dana Carney

Associate Professor; Director, Institute for Personality and Social Research

Topics: Cultural impact of social distancing

Professor Emeritus, Management of Organizations and UC Berkeley Center for Catastrophic Risk Management

[email protected]

(510) 642-5221

Topics: Managing crises, highly reliable organizations, organizational resilience

Kurt Beyer

Kurt Beyer

Senior Lecturer, Entrepreneurship

[email protected]

(415) 412-9551

Topics: Innovation during recessions, strategy, entrepreneurship, intrapreneurship in large organizations

Alex Budak

Alex Budak

Lecturer, Management of Organizations

Topics: Leadership, management, and adapting to/thriving during change and uncertainty

Peter Wilton

Peter Wilton

Senior Lecturer, Marketing

[email protected]

(415) 425-5151

Topics: Leadership and general management; impacts on innovation and customer loyalty in turbulent times

Workplace Impacts & Remote Work

Clark Kellogg

Clark Kellogg

Lecturer in Creativity, Design, and Innovation

[email protected]

(510) 388-2967

Topics: Working remotely, resilient responses and creative problem solving in the midst of chaos

Molly Turner

Molly Turner

Lecturer, Business & Public Policy

Topics: Impact of telecommuting on urban development, urban innovation, technology and cities, economic development and tourism policy

Sahar Yousef

Sahar Yousef

Lecturer

Topics: How to maintain productivity, effectiveness, and motivation across teams while people are working from home, cognitive neuroscience

Marissa Saretsky

Marissa Saretsky

Lecturer, Responsible Business

Topics: Responsible steps that business must take to protect employees, suppliers, and customers; how can businesses take a leadership role in the crisis

Rebecca Portnoy

Rebecca Portnoy

Lecturer, Management of Organizations

[email protected]

(206) 890 8374

Topics: Leadership, remote work, virtual meetings, creating engaging experiences

Supply chains

Olaf Groth

Lecturer, Business & Public Policy

[email protected]

(415) 205-0807

Topics: Global tech supply chain security; AI & IOT; data markets; privacy & surveillance computing; future of work; business & policy; tech ethics & governance.

Industries

Adam Leipzig

Adam Leipzig

Lecturer, Persuasive Communication & Interpersonal Dynamics

[email protected]

(323) 791-0255

Topics: Impact on the film, entertainment, media, content creation and creative industries

How a surgeon saw an MBA as key to his future in healthcare

Terrell Baptiste, EWMBA 20, on investing in better healthcare for marginalized communities

Listening to people’s stories about their problems as a young legislative aide in Texas ignited Terrell Baptiste’s interest in healthcare policy as a way to improve lives on a larger scale.

That led Baptiste, EWMBA 20, on a career journey from Washington D.C., where he worked as a senior legislative associate in healthcare policy, and then in communications at the FDA, to Bay Area pharmaceutical company BioMarin, which specializes in rare diseases.

Now focused on investing in healthcare companies, he also volunteers at the MLK Jr. Outpatient Center in Los Angeles, which treats adults with sickle cell disease, a red blood cell disorder that disproportionately impacts the African American community.

We spoke with Baptiste about his healthcare journey, his commitment to improving healthcare in marginalized communities, and his most useful Berkeley courses.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Houston and went to high school in Sugarland, a wonderfully diverse community. I don’t identify as a Texan but I have a soft spot for Texas as it brings me positive memories and connects me back to my childhood.

How did you end up in the Texas legislature?

As an undergraduate student at the University of Texas in San Antonio, I became enamored with politics. One of my professors introduced me to a Texas state representative for whom I ultimately interned. Six months later I found myself running his re-election campaign and working 20 hours a day in the process. I’m still tired from that job!

Is that when you became interested in healthcare?

Yes, that’s where I found health policy. It was formative to me. I enjoyed the idea that I could listen to stories, help people, and make things happen from a legislative perspective. It lit a fire in me to figure out how I could make an even bigger impact for good.

So why did you end up choosing to get an MBA?

At the FDA, we would interact with pharmaceutical companies at a distance while we were evaluating their products. We would hear about the state of the companies, but I didn’t have the background to understand what certain things meant. I didn’t understand how the companies were being financially supported. I came to business school to understand more about that. My overarching goal with my career has been and is to improve the lives of marginalized patients and so I see my Berkeley MBA as a tool to further that objective.

Your plan is to shift over to biotech hedge fund investing? Why?

I never imagined I’d go from working with the FDA to actually evaluating these companies from an investment perspective at a biotech hedge fund. It’s nice to be able to take my understanding of the way the government thinks about treatments for people as well as the operating experience from BioMarin—where I worked as a regulatory policy analyst, pipeline commercialization associate, and global market access senior analyst—and apply that to investing roles. It’s not a traditional path. I am able to conceptualize what people are doing and see it from different angles.

Which MBA courses have you found most useful to your job?

The entire core program at Haas gives you a fluency in business. You share a common language with people around the world, and a conceptual framework. Turnarounds: Effective Leadership in Crisis with Peter Goodson helped me conceptualize as an investor what options CEOs have and what companies are going through. I took M&A at Berkeley Law with Steven Davidoff Solomon. I wanted a deeper understanding of M&A and I wanted to understand what the process was. This course wasn’t about value creation, but about the legal mechanics behind deal making. I wanted to educate myself on that as an investor or future operator.

What led you to volunteer at the sickle cell center?

At the Sickle Cell Clinic at MLK Jr. Outpatient Center, I’m a lead author of a research study on the impact of innovative adult sickle cell care. My experiences in Washington D.C. and at the FDA have allowed me to see firsthand how a marginalized community can receive uneven care, especially for a disease with limited treatment options.

Working with marginalized populations makes sense to me because you need to have core values connected to the work you do. One main reason I went to France to study for a semester last spring is that I wanted to go to a country that believes that philanthropic and social values are connected to work. I wanted to see that live in action. Here, I’d like to continue to have a hybridized world where I work with real patients and I do projects to support them, and where I can also work as a healthcare investor.

Focus rooms, collaboration lounges, and nature views: New book explains how office design fads fall short

Sit-stand desks, “collaboration lounges” sprinkled among cubicles, “focus rooms” for privacy, and windows with views of nature are all among today’s cool office trends.

But here’s the rub. As amazing as modern offices appear to be, they may not be helping employees do their jobs. They may even be distracting them from getting work done.

That’s the premise of a provocative new book co-authored by Berkeley-Haas Senior Lecturer Cristina Banks. In Built to Thrive: How to Build the Best Workplaces for Health, Well-Being, & Productivity, Banks and her collaborators combine research insights and workplace experiences to argue that too much attention is paid to physical space at the expense of the psychological and social needs of today’s employees.

Case in point: sit-stand desks. While they’re meant to get workers up on their feet for health reasons, studies show the novelty quickly wears off and employees mostly sit. “Collaboration” lounges rarely get used because they’re too close to cubicles. “Focus” rooms are rarely soundproof, meaning conversations intended to be private aren’t. And what about those outside views of trees and grass? The only beneficiaries are people who work on the office periphery.

Though well-intentioned, piecemeal features like these don’t go nearly far enough to promote employee health and well-being. “They miss a fundamental understanding of what leads to employee productivity and that is a multi-pronged approach,” says Banks, who teaches management and also serves as director of the UC Berkeley Interdisciplinary Center for Healthy Workplaces (ICHW), which published the book. Berkeley Haas also sponsors the Center.

“Built to Thrive” relies on empirical research findings and professional advice to make the case for why a holistic understanding of the physical, emotional and social needs of employees is crucial in today’s workplace. The book’s 10 authors, each of whom contribute a chapter, are experts from a number of fields including environmental psychology, real estate, architecture, public health, and design strategy.

The authors argue that to inspire motivation and a sense of well-being businesses should pay attention to autonomy, social connection, bodily security, and work with purpose. Physical spaces, they argue, either enhance or detract from those goals.

For example, environmental psychologist Sally Augustin writes about the important roles that mood and emotion play in the workplace. Extroverts, for example, are happy to sit on a sofa with coworkers and collaborate, while introverts prefer to sit behind a desk or table. Cognitive thinking improves under blue lighting, while warmer hues encourage more socialization. Even scents serve a purpose: the smell of lemon improves performance, while cinnamon inspires creativity.

In separate chapters, Gervais Tompkin, a principal with the global design firm Gensler, describes the power of experience in the workplace, including the use of sound and projections of nature on screens or augmented reality glasses. Kevin Kelly, a senior architect with the General Services Administration, explains why employees’ subjective opinions of their workspace matter more than objective reality. And Google executive Anthony Ravitz details how the company relies on employee surveys and other data sources to measure office quality.

The book ends with a general framework to guide businesses on their existing and future office design projects. The approach emphasizes user needs while also recognizing that all departments need to be integrated into the process. It also points out that creating an optimal workspace doesn’t have to be costly and can actually be fun.

“There’s this myth that designing wellness into the workplace is more expensive than not doing it,” says Banks. “This book shows why that’s not the case, and why office design needs to be among the top three concerns for any business leader.”

How opioid use spreads in families, worsening crisis

Berkeley Haas researchers have identified another driver of the opioid epidemic in the United States: family ties.

In a new study published in American Sociological Review, Asst. Prof. Mathijs de Vaan and Prof. Toby Stuart show that the likelihood of someone using opioids increases significantly once a family member living in the same household has a prescription. They also find that the chances of a relative obtaining a prescription for opioids within a year after a relative they live with gets one rises by 19 percent to over 100 percent, depending on family circumstances. Individuals from low-income households, for example, are the most likely to secure their own prescription after a family member does.

The study is one of the few analyses of the opioid crisis that finds a causal link between a specific action—in this case, the introduction of painkillers into a home—and their growing use. In all, de Vaan and Stuart analyzed hundreds of millions of medical claims and almost 14 million opioid prescriptions written between 2010 and 2015 and contained in a database operated by the state of Massachusetts. They were able to track family members’ health care through shared medical insurance policy numbers.

“Our research finds huge effects on the likelihood that family members who are influenced by other family members will start using opioids,” says de Vaan, a sociologist who studies social networks.

“Social contagion”

De Vaan and Stuart, who holds the Leo Helzel Chair in Entrepreneurship and Innovation at Haas, suggest two reasons for this contagion: when a family member takes painkillers, other relatives in the home observe firsthand its effects. Patients also typically receive more pills than they need, which means relatives may be tempted to experiment with leftovers sitting in the medicine cabinet.

Family members’ exposure to painkillers then increases the likelihood that they will visit a doctor within a year and obtain their own prescription. Other research has shown that Americans are more willing to ask for—and receive—specific treatments than consumers in other countries.

Because of this, de Vaan and Stuart offer a new insight into the role of physicians in the opioid epidemic. While it’s long been believed that physicians who work in the same community or are connected in other ways rely on each other for advice and adopt similar forms of treatment, the authors show that the explosion in opioid prescription rates may be coming from patients, too.

“The actions of one doctor toward one patient affect the requests that that patient then makes of other doctors he or she visits,” says de Vaan. “We find that physicians are not only influencing each other directly when it comes to opioid prescriptions. They’re influencing each other by steering patient demand.”

A causal link

Sociologists have long studied the role that social networks have on people’s health. Smoking and alcohol use are two prominent examples of habits families often share.

The problem with research into social contagion is that most of it identifies correlations, but can’t establish cause and effect. It’s possible that other factors—like genetics or the tendency for people to marry others like them—come into play, too.

De Vaan and Stuart, however, were able to establish a causal link between opioid prescriptions and an increase in the drug’s use within families. They did this by narrowing their research to emergency room visits only, where patients are randomly assigned to doctors who prescribe opioids at vastly different rates—so the likelihood that one patient received a painkiller prescription over another was random. The experiment also eliminated the possibility that family members who later got a prescription got one from the same doctor or that family members were visiting the same provider, such as a primary care physician.

Finding prevention methods that work

De Vaan and Stuart suggest several steps to address the spread of opioid use within families. To prevent so-called “doc shopping,” states that track prescription drug use and make that information available to doctors could also include data on family members’ access to medications. To avoid violating the privacy of relatives, de Vaan says the program could simply issue a “risk” score that would signal to doctors that their patient has been indirectly exposed to painkillers at home.

Policymakers could also expand upon existing efforts to collect leftover prescription drugs—namely through National Prescription Drug Take Back Day—by paying people to return their excess supply. The upfront costs would likely be offset by the money saved in addiction treatment and other costs, de Vaan says. Doctors should also be trained on how to push back when patients ask for painkillers.

“We’ve identified a specific driver of opioid consumption, so all of these steps make a lot of sense,” de Vaan says.

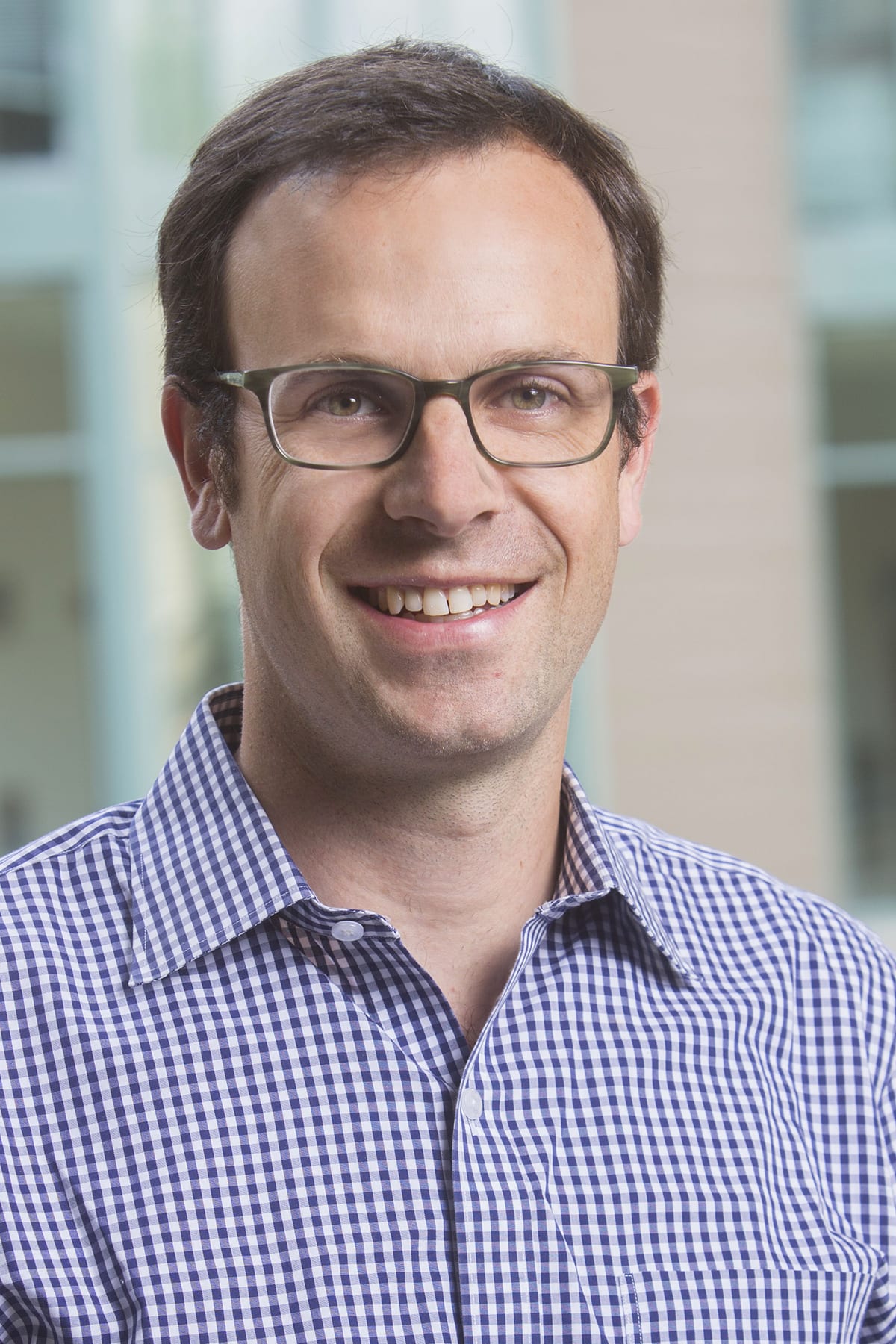

Assoc. Prof. Kolstad honored as top health economics researcher under 40

Assoc. Prof. Jonathan Kolstad has received the top award from the American Society of Health Economists for researchers under age 40 who have made the most significant contributions to the field of health economics.

He shares the 2018 ASHEcon Medal with his collaborator, Assoc. Prof. Benjamin Handel of Berkeley’s Economics Department.

Kolstad said he’s honored to be recognized, relatively early in his career, for a larger contribution than just one paper, and for an ongoing collaboration.

“The fact that this was given jointly to Ben Handel and myself reflects an appreciation for some of the new avenues we’ve taken in health economics,” he said. “Much of our joint work has brought new data to bear on old problems that have really different implications when you get into how people actually behave, not just how we assume they behave. ”

Drawing on big data and behavioral economics

Kolstad’s research focuses on the intersection of health economics and public economics, and his work with Handel has also combined approaches from industrial organizations as well as behavioral economics. Their interdisciplinary, cross-departmental collaboration reflects the strength of health economics at UC Berkeley.

“We are very happy to have (Kolstad) at Haas, and we’re pleased by how he is helping to build interest in healthcare economics at Haas and across the Berkeley campus,” said Prof. Candi Yano, associate dean for academic affairs and chair of the faculty.

Recently, Kolstad and Handel have been working with a massive trove of health data on the entire population of the State of Utah over a long time period. The richness of the data has allowed them to analyze the different outcomes from different health insurers and health plans.

“We’re finding very large effects and big differences,” Kolstad said. “Simply changing insurers at the same employer—something most people encounter with some frequency—has huge effects not only on how much is spent on your health care, but also on how your healthcare is delivered.”

The researchers are now looking at what employers look for in choosing insurers and health plans, to answer the question of whether competition actually leads to “productive innovation”—i.e, improving care and lowering costs.

Data partnerships

Kolstad and Handel are also working on partnerships with a number of private companies, from digital health to employers and health care providers, to leverage their data for new research. “This is a particularly exciting area,” he says. “Collaboration between academics and private firms, particularly technology companies, is driving a lot of new findings. We hope to make similar strides on big health care questions.”

Since arriving at Haas from Wharton in 2015, Kolstad has brought his expertise with big data into the MBA curriculum, including developing a new “Big Data and Better Decisions” course that he co-taught with Prof. Paul Gertler this spring. Earlier this year, he was honored as a “40 Under 40” business leader by the San Francisco Business Times for his work as a cutting edge researcher, teacher, and entrepreneur. He founded a startup, Picwell, which now provides more than 1 million personalized insurance recommendations per year.

He said he’s excited by the practical applications of his academic work. “We all deal with our health, and the policies and products in the industry affect our everyday lives. The recognition for this work and its importance to the field will hopefully continue to push health economics more in this direction.”

Saving Lives by Making Malaria Drugs More Affordable

Study determines offering drug retailers a per-unit purchase subsidy benefits patients

Forty percent of all malaria-caused deaths in sub-Saharan Africa occur in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria, according to the World Health Organization. The private sector “supply chain” manages 74% of the drug volume in Congo and 98% in Nigeria where malaria-stricken patients rely on “drug shops” and other for-profit retail outlets to get life-saving medicine.

New research forthcoming in Management Science determines that the “shelf life” of malaria-fighting drugs plays a significant role in how donors should subsidize the medicine in order to ensure better affordability for patients.

New concerns over the emergence of drug resistant parasites are yet one more reason that private donors who fund malaria drug programs remain intent on making medicine available and affordable to patients. Artemisinin-based combination therapies, known as ACTs, are considered the best anti-malarial drugs but the lack of affordable ACT supplies for the poor motivates private donors to intervene and improve access.

In “Subsidizing the Distribution Channel: Donor Funding to Improve the Availability of Malaria Drugs,” Terry Taylor, associate professor, UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, and co-author Wenqiang Xiao, New York University’s Stern School of Business, analyzed purchase subsidies vs. sales subsidies.

In “Subsidizing the Distribution Channel: Donor Funding to Improve the Availability of Malaria Drugs,” Terry Taylor, associate professor, UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, and co-author Wenqiang Xiao, New York University’s Stern School of Business, analyzed purchase subsidies vs. sales subsidies.

Donors structure their purchase and sales subsidies per each product unit. A purchase subsidy is a discount or rebate offered to the retailer at the point of sale or when he places his order. In contrast, the retailer only benefits from a sales subsidy when he sells the product to the consumer.

By analyzing the product characteristics (short vs. long life), customer population (degree of heterogeneity or diverse makeup), and the size of the donor’s budget, Taylor and Xiao found that for long shelf life products, such as ACTs (with a 24 to 36-month life from the factory to expiration), donors should only offer a purchase subsidy. In contrast, if a product has a short shelf life, a sufficiently large donor budget and a diverse customer population, it is optimal to offer a sales subsidy in addition to a purchase subsidy. Why?

“The sales subsidy becomes more attractive for perishable products because you don’t have to subsidize a purchased product that doesn’t sell,” says Taylor.

Unlike previous research, the study’s micro-level approach focuses on distribution channel details such as demand uncertainty, supply-demand mismatch, and the impact of subsidies on stocking and pricing decisions.

“In principle, it would seem that you would want to use both levers to influence stocking and pricing decisions,” says Taylor. “However when we took both into account, our model shows that the purchase subsidy is more effective in increasing consumption of the medicine and ultimately, saving lives.”

Taylor hopes these findings will help guide donors in improving the private-sector distribution channel for malaria drugs. He hopes that in the future, the study’s results could also help inform subsidy decisions for other global health products such as oral rehydration salts, the first-line of treatment for childhood acute diarrhea in developing countries.

Research by Prof. Terry Taylor, forthcoming in Management Science, determines that the “shelf life” of malaria-fighting drugs plays a significant role in how donors should subsidize the medicine in order to ensure better affordability for patients.

Study Shows Early Childhood Stimulation Intervention in Jamaica Yields Better Pay in Adulthood

In the May 30, 2014 edition of the journal, Science, researchers find that early childhood development programs are particularly important for disadvantaged children in Jamaica and can greatly impact an individual’s ability to earn more money as an adult.

The 20-year study, “Labor Market Returns to an Early Childhood Stimulation Intervention in Jamaica” by Professor Paul Gertler, an economist at the Haas School of Business and the School of Public Health, and Nobel Prize winner James Heckman of the University of Chicago, tracks the employment status of adults who once lived in the poor Kingston neighborhood as toddlers in the 1980’s. Those exposed to high-quality psychosocial stimulation have positive earnings and better economic status today.

In the program, designed by Sally Grantham-McGregor of University College London and Susan Walker of the University of West Indies, community health workers made weekly home visits and taught mothers how to play and interact with their children in ways that promote cognitive and emotional development. For example, mothers were encouraged to talk with their children, to label things and actions, and to play educational games with their children, emphasizing language development and the use of praise to improve the self-esteem of mothers and children.

Mirroring the mission of the Head Start program in the United States, this simple intervention focused on reducing developmental delays faced by children in poverty.

Twenty years later, the researchers interviewed 105 of the study’s original 127 child participants who were now adults. They found that children randomized to participate in the program were earning 25 percent more than those in the control group, enough of an increase to match the earnings of a non-disadvantaged population. The intervention compensated for the economic consequences of early developmental delays and reduced later-life inequality.

“To our knowledge, this is the first long-term, experimental evaluation of an early childhood development program in a developing country,” said Gertler, who also works with the Center for Effective Global Action (CEGA), a UC Berkeley-based research network designing anti-poverty programs for low- and middle-income countries.

“To our knowledge, this is the first long-term, experimental evaluation of an early childhood development program in a developing country,” said Gertler, who also works with the Center for Effective Global Action (CEGA), a UC Berkeley-based research network designing anti-poverty programs for low- and middle-income countries.

This study adds to the body of evidence, including Head Start and the Perry Preschool programs carried out from 1962-1967 in the U.S., demonstrating long-term economic gains from investments in early childhood development.

“Head Start programs are critical to breaking the cycle of poverty,” said U.S. Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Calif.), a member of the Labor and Education Appropriates Committee. “By investing in the academic and developmental needs of young children, we are preparing them to thrive in the economy of the future.

Results from the Jamaica study show substantially greater effects on earnings than similar programs in wealthier countries. Gertler said this suggests that early childhood interventions can create a substantial impact on a child’s future economic success in poor countries.

“We now have tangible proof of the potential benefits of early childhood stimulation and the importance of parenting in a developing country. At a time when inequality around the globe is increasing, it is encouraging to see how much good can be accomplished with early intervention,” Gertler said.

CEGA designs and tests solutions for the problems of poverty, and draws on a network of faculty researchers at the University of California, Stanford University, and the University of Washington who combine randomized trials, behavioral experiments, data analytics, and novel measurement technologies with expertise in international agriculture, health, education, engineering and the environment.

In the May 30, 2014 edition of the journal, Science, researchers find that early childhood development programs are particularly important for disadvantaged children in Jamaica and can greatly impact an individual’s ability to earn more money as an adult. The 20-year study, “Labor Market Returns to an Early Childhood Stimulation Intervention in Jamaica” by Professor Paul Gertler tracks the employment status of adults who once lived in the poor Kingston neighborhood as toddlers in the 1980’s.

Bonuses for Doctors Pay Off for Patients

A study in Rwanda by Prof. Paul Gertler shows that financial incentives for medical providers improve service and health outcomes.

Video: Watch Prof. Gertler talk about his research.

Everyone knows money talks. Prof. Paul Gertler found this to be the case in Rwanda, where, in conjunction with the national government, he evaluated a new and novel pay-for- performance model for the health care industry designed to increase access to high quality maternal and child health services.

He outlines his findings in his paper, “Using Performance Incentives to Improve Medical Care Productivity and Health Outcomes,” co-authored by Christel Vermeersch, a World Bank senior economist.

“Instead of investing more in the current healthcare system, we can try to get more out of our existing resources. The problem in Rwanda and most of the world is that medical care providers’ deliver a quality of care that is below their capabilities and training,” says Gertler, director of the UC Berkeley Clausen Center for International Business and Policy and the Li Ka Shing Foundation Chair in Health Management.

“Instead of investing more in the current healthcare system, we can try to get more out of our existing resources. The problem in Rwanda and most of the world is that medical care providers’ deliver a quality of care that is below their capabilities and training,” says Gertler, director of the UC Berkeley Clausen Center for International Business and Policy and the Li Ka Shing Foundation Chair in Health Management.

Gertler found that when providers were offered financial incentives, their compliance with clinical care guidelines increased by 30 percent and their productivity increased 20 percent. The study showed that these improvements resulted in large increases in child health outcomes as measured by increased height and weight of children treated by these providers.

The Rwandan government offered health care providers payments for services such as institutional childbirth deliveries and emergency referrals to hospitals for obstetric services, new contraceptive user visits, referrals of at-risk pregnancies to hospitals, and referrals of malnourished children to higher level facilities for treatment. For example, a provider receiving $.55 for four standard prenatal care visits received $1.47 for providing higher quality care such as administering tetanus and malaria vaccines or detecting a high-risk patient and referring her to a hospital.

The pay-for-performance model is now being tried in Africa and parts of Latin America and is an important part of Obamacare, according to Gertler. “One of the nice things about the Affordable Care Act or Obamacare is the plan to offer financial incentives for providers,” Gertler explains. “If we are going to make progress in reducing costs of Medicare and Medicaid, pay for performance can make the system more efficient and dramatically improve the quality of health care.”

Everyone knows money talks. Prof. Paul Gertler found this to be the case in Rwanda, where, in conjunction with the national government, he evaluated a new and novel pay-for- performance model for the health care industry designed to increase access to high quality maternal and child health services.

He outlines his findings in his paper, “Using Performance Incentives to Improve Medical Care Productivity and Health Outcomes,” co-authored by Christel Vermeersch, a World Bank senior economist.

Karlene Roberts

Karlene Roberts