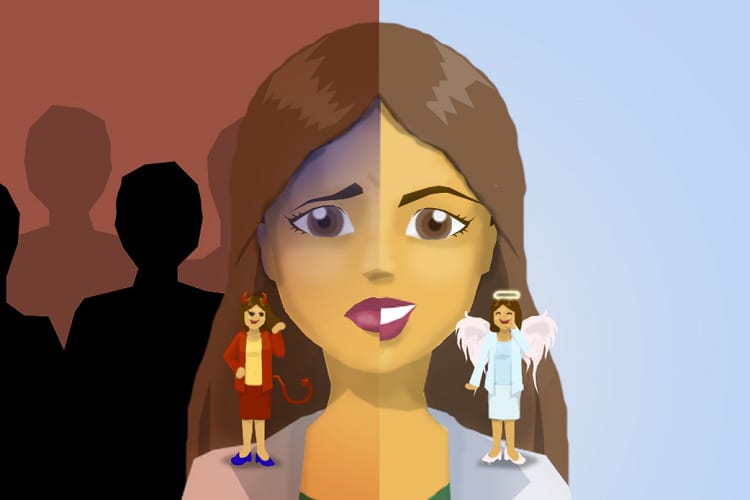

Would you tell a lie to help someone else? A new study says women won’t lie on their own behalf, but they are willing to do so for someone else if they feel criticized or pressured by others.

In contrast, research by Prof. Laura Kray of UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business and Asst. Prof. Maryam Kouchaki of Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, found that men are the opposite: they do not compromise their ethical standards under social pressure regardless of whether they’re advocating for themselves or anyone else.

Their paper, “‘I’ll Do Anything For You.’ The Ethical Consequences of Women’s Social Considerations,” received the Best Empirical Paper Award from the International Association of Conflict Management (IACM) on Jun 28.

Their paper, “‘I’ll Do Anything For You.’ The Ethical Consequences of Women’s Social Considerations,” received the Best Empirical Paper Award from the International Association of Conflict Management (IACM) on Jun 28.

“We found that when women act on their own behalf, they maintain higher ethical standards than men. However, women will act less ethically, such as telling a lie, when they fear being viewed as ineffective at representing another person’s interests,” says Kray. “When women negotiate on behalf of someone else, they are willing to make compromises in order to satisfy the needs of others.”

But at what cost?

Kray says there’s a tradeoff for women, who face a “Catch 22.” Men are typically less constrained by social expectations. But when women are asked to advocate for others they face a conflict because they must either relinquish or reduce their usual moral standards, or open themselves up to possible social backlash.

The authors write, “they are damned if they lie because it goes against their communal mandate with respect to their negotiating counterpart, however they are damned if they do not lie because it goes against their communal mandate with respect to the party they are representing.”

The findings are a result of four studies, each involving from 160 to 235 participants.

In the first study, participants were assigned either self-advocacy or friend-advocacy roles and asked to consider the appropriateness of various negotiating tactics. As hypothesized, women who negotiated on behalf of someone else were less ethical than when advocating for themselves.

The second study was designed to better understand the psychological process behind unethical negotiating tactics. Participants advocating for others answered questions about how much they anticipated social backlash if they did not reduce their ethical standards to help others. For example, “How much would your friends like to socialize with you?” and “How likely would your colleagues be to go with you if you invited them out for drinks after work?” The findings were the same as in the first study. However, women were not found to completely disregard — only lower — their moral obligations regardless of whether they were advocating for themselves or others.

“This suggests that women did not see unethical tactics as more acceptable when helping others but instead, they lowered their ethical standards because they felt pressured to do so,” says Kray.

The third study focused on the anticipation of social backlash. Female participants were asked to read a description of a salary negotiation from a self-advocacy perspective; for example, as new recruits negotiating their own starting salary. They also read a description depicting an other-advocacy situation such as a friend negotiating salary on behalf of a new recruit whom she referred for the position. The ethical dilemma of each script is whether to tell the hiring manager that they (or the friend) had another job offer even though one didn’t really exist. The alternative option was to be honest with the hiring manager and tell him that they (or the friend) had no other job offers. Women were more inclined to lie when negotiating for the friend.

In the final study, the authors recruited participants (49% male; 51% female) to complete an actual negotiation and assigned them to be either a property seller or a buyer. In the scenario, the seller wants to sell to a buyer who would retain the property for residential use. However, buyers were instructed that their intent was to turn the property into a high-rise, commercial building against the wishes of the seller. Would those negotiating on behalf of the buyer be deceptive as a result of social pressure? Again, women who chose to be dishonest expected greater social backlash when negotiating for themselves than on behalf of others. And, women who chose not to lie anticipated greater backlash when representing someone else’s interests.

Across all studies including men, the men’s ethics were not affected whether they represented themselves or another person. Also, their ethical standards were lower than women representing themselves.

The study’s results may appear disturbing to women who are trying to do the right thing, but Kray contends that when considering whether to compromise one’s usual ethics, consider the particular situation. Women may be unaware that they have this tendency to lower their moral standards when trying to help others.

“Ask yourself, ‘What are the constraints and social pressures? If I was doing this for myself or someone else, how would I act differently,” says Kray.

Would you tell a lie to help someone else? A new study says women won’t lie on their own behalf, but they are willing to do so for someone else if they feel criticized or pressured by others. In contrast, the study, co-authored by Prof. Laura Kray, found that men are the opposite: they do not compromise their ethical standards under social pressure regardless of whether they’re advocating for themselves or anyone else.