The first large-scale analysis of traffic congestion in 154 Indian cities has identified the slowest urban areas, and found that the problem may have more to do with poor road infrastructure than the number of cars on the road.

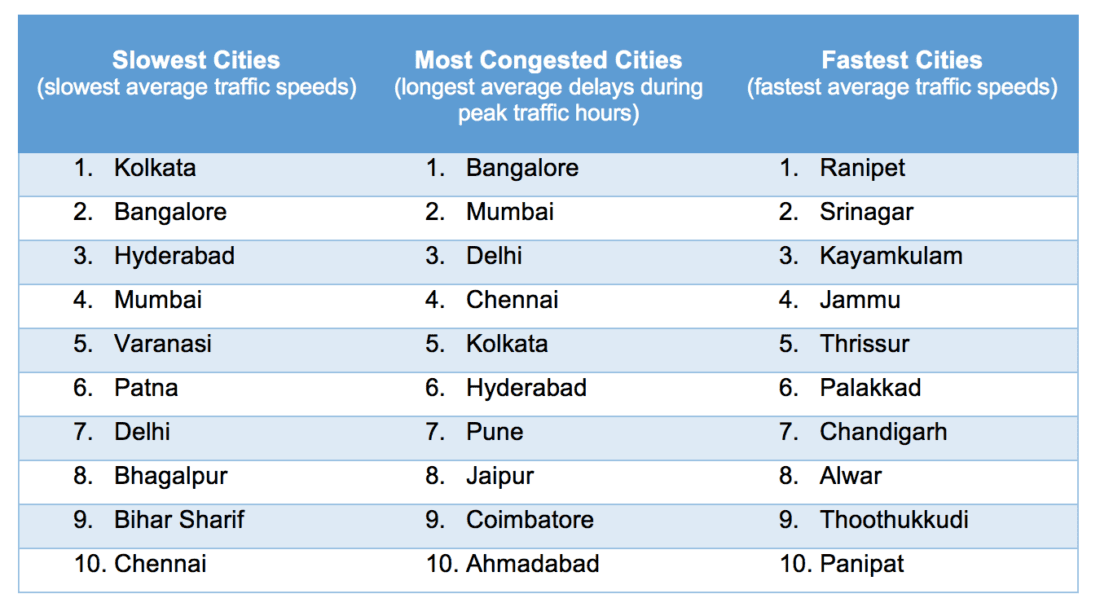

A team of researchers at the University of California, Berkeley and three other U.S. universities used Google Maps to analyze 22 million potential trips throughout India’s largest cities. They pinpointed the cities where traffic moves the fastest, those where it moves the slowest, and those with the longest peak traffic delays or congestion. In the slowest cities, traffic moves at less than half the speed as in the fastest cities, and it’s slow around the clock.

Asst. Prof. Victor Couture

“There is a great deal of concern about slow travel in Indian cities, but attempts to quantify the problem have been quite limited so far,” said study co-author Victor Couture, assistant professor of real estate at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. “These findings challenge the conventional wisdom that rush-hour congestion is to blame for slow traffic.”

Kolkata, for example, is the slowest city in India, but it’s only the fifth most congested. Hyderabad is the third slowest city, yet it’s the sixth most congested, researchers determined.

“To our surprise, traffic congestion has a minimal impact outside of the very few largest cities, such as Mumbai and Delhi,” said Gilles Duranton, professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and a study co-author, along with Adam Storeygard, associate professor of economics at Tufts University, and Prottoy Akbar, doctoral researcher at the University of Pittsburgh. “Roughly speaking, this means that cities that are slow relative to other cities at rush hour are also relatively slow at 3 am with few cars on the road.”

The study, published today as a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, has important policy implications. While congestion alleviating policies are potentially useful in the few most congested cities, such as Bangalore and Mumbai, they are unlikely to make much of a difference in cities where traffic is chronically slow, such as Varanasi, Storeygard said.

“Uncongested speed in the slowest cities can’t be improved by ride-sharing, congestion pricing or other restrictions, and it may be more beneficial to invest in infrastructure,” he said.

Most large transportation studies have relied on household travel surveys, which are expensive and carried out only once every several years—even in wealthy countries. The research team found a cheaper large-scale alternative: real-time travel data from Google Maps, which are based on the location and speed of hundreds of millions of mobile phones running Google’s software. The researchers designed sample trips and tested them at different times over 40 days in 2016, factoring in local holidays and weather conditions. They also used government survey and census data on earnings, population, car access, and average commute distances, as well as various data sources on city shape and road networks.

“Travel survey respondents only report data on the trips they choose to take, not the ones they decide against,” said Akbar. “The Google data give us a much broader sense of the traffic conditions affecting choices.”

While the study did not isolate the exact causes of slow traffic, the results pointed to poor infrastructure as the likely culprit. Cities with more primary roads and those laid out in a more regular grid are faster. For example, Chandigarh—a planned city laid out in a grid—is India’s 12th most congested city, yet it’s also the 7th fastest.

The findings also show that urbanization and rapid growth don’t have to lead to gridlock—in fact, the researchers found that economic development can bring better infrastructure and improve mobility. Indicators such as faster recent population growth, higher income, and higher rates of car use were associated with faster overall traffic speeds, despite worse congestion.

The researchers believe their new approach to studying traffic conditions may be useful throughout the developing world, where there has been a lack of comprehensive data about urban transportation.

“New forms of geographic data have great potential to teach us about urban transport,” Couture said. “We hope our results, methodology, and data sources can help guide policy and future research on urban transportation in developing countries.”

City Rankings

RESOURCES & CONTACTS

“Mobility & Congestion in Urban India,” NBER Working Paper

Victor Couture, Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley: [email protected]

Adam Storeygard, Tufts University: [email protected]

Gilles Duranton, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania: [email protected]

Prottoy A. Akbar, University of Pittsburgh: [email protected]