In honor of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, we’re featuring profiles and interviews with members of our Haas community.

Prof. Candi Yano‘s family immigration history is one of twists and tragic turns, from Japan to the U.S., and back and forth again.

Yano, who is wrapping up her term next month as the first Asian-American woman to serve as Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and chair of the Berkeley Haas faculty, is an international expert on supply chain management. After three years of helping to win faculty retention battles and countless hours serving colleagues needs big and small, she looks forward to returning to her dual academic role as the Gary & Sherron Kalbach Chair in Business Administration at Haas, and as a professor in the Department of Industrial Engineering & Operations Research.

In between writing her last few memos as faculty chair, Yano took the time to share her family’s fascinating—and heart wrenching—immigration story, as well as the circuitous route she took to discovering the focus of her life’s work via a copy machine at Stanford University.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in a city called Gardena, immediately south of Los Angeles. When I was a kid, about half the population there was Japanese American. My high school was more diverse because of busing in the L.A. school district. There were lots of Hispanic students who were mostly local, and African-American students who were bused in from adjacent communities, as well as Asian and Caucasian students. It was interesting to leave home for the first time and realize the whole world wasn’t like that. I ended up at Stanford, and at that point only about 10% of the students were Asian American. It was eye-opening for me.

What was the history of Gardena, and how did it end up half Japanese American?

When my grandparents immigrated from Japan about a hundred years ago, people weren’t coming in big groups, and so they wanted to go to a place where they felt more comfortable. Many of them were young men and some of them were still in their late teens. It’s really amazing to think about them just getting on ships by themselves. That particular area, even though it’s heavily populated now, was mostly fields—lots of strawberries. My paternal grandfather came from a farming background. He came to California because he felt he had good job opportunities along the lines of what his family had done. My maternal grandfather immigrated a bit later, and I know less about his reasons for coming the the U.S.

When did your grandparents arrive?

It was around the late teens, maybe early 1920’s. Then in 1924, the U.S. government decided to cut off Asian immigration with the Asian Exclusion Act. I believe both of my grandfathers were here in the U.S. and they sent for their wives-to-be from Japan, because they all had arranged marriages back then. They came over and got married and started their families.

Did you know your grandparents growing up?

Yes, except my mother’s father, who was killed by the bomb in Hiroshima during the second World War.

Wow. How did that happen, if he had immigrated to the U.S. before the war?

After they had been sent to a relocation camp, my grandfather decided he didn’t want his family being locked up. There were two choices: Stay in the camp or go to Japan. So he decided to take them to Japan, which of course my mother probably didn’t like very much because she was born in the U.S. My grandfather had been a newspaper editor in California, and he picked up that line of work there as an editor at the big regional paper in Hiroshima, The Chugoku Shimbun. He was in the wrong place at the wrong time. My mother seems to have survived mostly unscathed because the family was living out in the burbs. Her mother raised the four kids alone after that. They all ended up coming back to the U.S. at different times. My mom came back at the age of 16. She had finished high school there, and then finished out high school again here.

That’s a heartbreaking story.

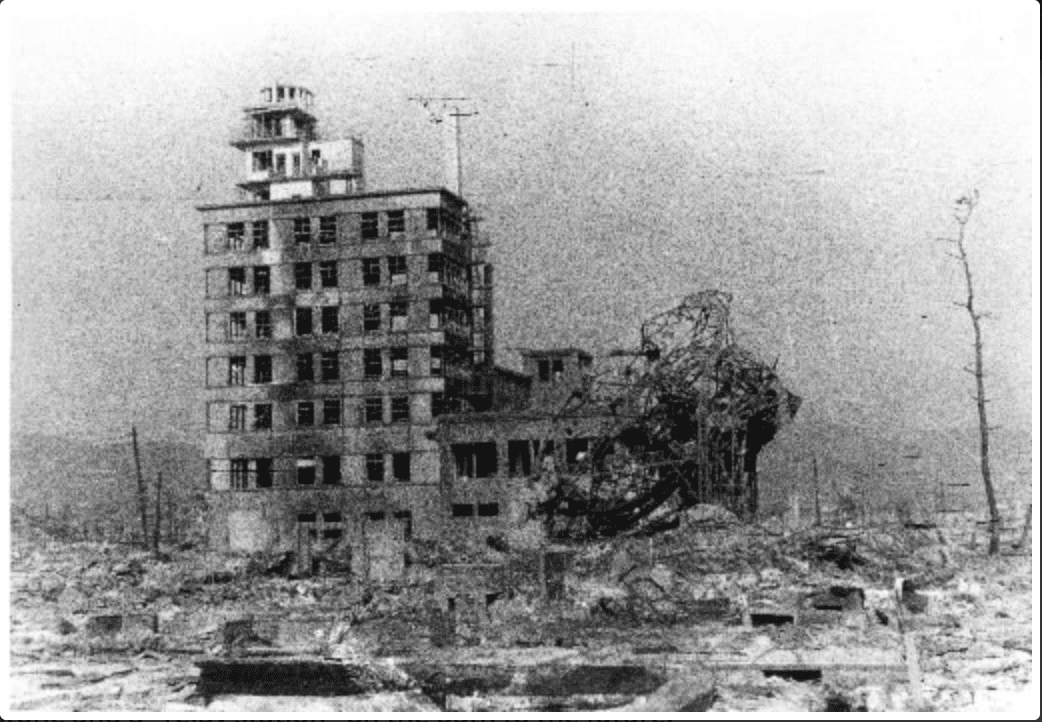

Yes, it really is. I had a chance to finally go to Hiroshima a couple of years ago. The Chugoku Shimbun newspaper is still in existence. I saw many panoramic pictures showing the buildings as they were after the bomb. It was heart wrenching to see that.

Did other members of your family who stayed in the U.S. have to go to the relocation camps?

All of them. My dad’s family was sent to a camp in Gila River, Arizona. They stayed there until they were released after the end of the war.

Did you grow up hearing stories about what happened during the war, or did they avoid talking about it?

I think it affected people differently depending on their age. My parents were both school-aged at the time, which meant that their parents were protecting them from the worst of it. It’s interesting that they don’t seem to have very negative feelings about what happened. But if you talk to people who are just 10 years older, who were adults at the time, they feel very differently. I think if my parents had been bitter they would have passed it on to me, but they weren’t. And in a sense, I consider myself lucky. I can be Japanese-American but not live with that sense of bitterness.

Did you learn much about Asian or Asian-American history in school?

Some, of course, but it was not covered very thoroughly. When I was in high school, most of the talk was about Russia and China. I did have a U.S. history class that required a term paper, and I wrote about the connections from Pearl Harbor to the Japanese surrender. I came to understand that one of the reasons why the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki was because the U.S. didn’t understand that the Japanese were ready to surrender—but they wanted to retain their emperor, even though he was more of a symbol. The U.S. was being too stubborn about the whole emperor issue, because we don’t have emperors, we don’t have kings and queens in the United States. That was a cultural misunderstanding. Not understanding the roles of various people in government really led to some undesirable outcomes.

An especially tragic example of cultural misunderstanding.

Shifting gears, how did you decide on an academic career, and how did you choose operations as your field?

I took a rather circuitous route. I was studying a lot of math in high school but I was becoming disillusioned with it, so I tried psychology. But when I volunteered as a so-called research assistant for a PhD student, my job was babysitting the five-year-old research subjects. I didn’t really like that. I ended up taking courses on the quantitative end of economics, but meanwhile, I had this odd part-time job. The operations research department at Stanford allowed its PhD students to use the photocopy machine, but they charged a per-copy price plus sales tax. My job was to tally up all the copies and calculate the charges including sales tax, and get the bills sent to the PhD students. As a consequence, I got to know the operations research department chair, and he encouraged me to apply to that department. It was entirely random; I could have had a different part-time job. I did get my undergraduate degree in economics but I eventually did a master’s in operations research and then my PhD in industrial engineering.

Were you in the minority as a woman in that department at the time?

There were at least 25% women in my class, but I never really felt like a minority. Actually, I never really felt discriminated against as a woman throughout my graduate career. Not within the campus environment. There were fair number of Asian students at the time too.

How did you end up at Berkeley?

My first full-time job was at Bell Labs in New Jersey. I decided to take an industry job because I had no full-time work experience and I thought it would be helpful. But it was the wrong time to be there, because it was during the first break-up of the Bell system, transitioning from a monopoly to a competitive environment. The antitrust judge kept on changing his mind, so we never got to finish anything. I was there for 17 months and I don’t think I finished a single project. I had been thinking about going into academia anyway and I said, “I think it’s time to go.” I ended up on the faculty at the University of Michigan and I stayed for about 10 years. But my husband grew up in Berkeley and he decided to take a job out here, so I had to figure out whether I wanted a long-distance relationship. I was lucky enough to get National Science Foundation grant for women faculty to spend a year at another university, and I came to Berkeley as a visiting faculty member. Then I was then lucky enough to get a visiting position at Stanford for another year and have the time to think about it. And then I decided to come back to Berkeley.

You’re wrapping up next month after three years as chair of the Berkeley Haas faculty. How has that been?

Well, first let me tell you about the best part of it. The best part is that I’ve really gotten to know the other faculty in a way that would not have happened otherwise. We have over 80 faculty members and I don’t run into everybody on a regular basis, but I’ve had an opportunity to get to know some really interesting people. I’ve tried to do what I could to help with whatever they they needed. The administrative work has been busy but not very intellectually stimulating.

Do you think this experience will influence your work going forward?

I think there are people I’ve met who I may be interested in collaborating with, but I haven’t had much time to think about it. Right now, I would just like to finish my last 10 memos (this job entails writing a lot of memos) and get back to being a normal person again. I need to do research for my own sanity.

What do you like best about research?

From when I was very young, I got intellectually bored easily, and I need to have something that keeps my mind going. I like finding new things, working on problems that other people have not tried to tackle before. I also like teaching, and I’ve only taught one class in the last four years, so I’m really looking forward to that.

What do you love about teaching?

I really like imparting knowledge and skills to students to allow them to be better professionals when they graduate. I especially like the undergrads. They’re more like sponges. The MBA students are more focused on what it is they want. I have a funny story about an MBA student in my supply chain management class. He took a job at what was SanDisk, now merged into Western Digital. He told me after his interview that virtually every topic I taught in the class helped him to answer their interview questions. He said it was so easy for him to get the job. That feels good. I get little notes from students saying they were able to get their job at this consulting firm or that company because of something I taught them.

Do you feel like being Asian American gives you a different perspective in the classroom?

Obviously I bring the heritage with me, but I have also spent a fair amount of time in Asia, so I think I have a better understanding of the culture and values that the Asian students bring with them. It’s not unusual for Asian students, especially those whose parents are immigrants, to be caught between two cultures. A lot of times I can help them work through the challenge of finding their own career trajectory that might not have been what their parents had planned for them. Also, in my classes I try to help the students who are quieter. In some Asian cultures you don’t speak unless you’re spoken to. I try to draw them out. Because I’m Asian, they can look at me and they say, “She does understand.”

Do you wish there was better understanding of Asian culture in the U.S.?

We are in an environment nationally that is not helping people to be more inclusive. It feels like a divisive time in our world. But let me say something positive: I think here on campus it’s better than in most places. We can talk openly, and I think that helps. But in many industry sectors, the percentages of women and of minorities of all types are far lower than they should be. I really hope that people start to understand each other a little bit better and try to bridge those gaps.