Ahead of ClimateCAP Summit, Haas sustainability leaders provide roadmap for training climate leaders

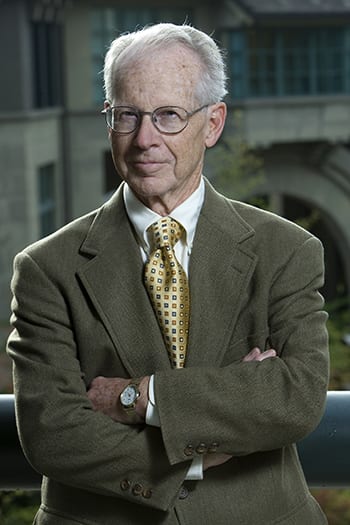

Oliver Williamson, a UC Berkeley and Haas School of Business professor for nearly three decades whose elegant framework for analyzing the structure of organizations won him a Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, passed away on May 21, 2020 in Oakland, Calif. at the age of 87. His death followed a period of failing health.

“Williamson’s work permanently changed how economists view organizations,” said Prof. Rich Lyons, who was dean of the Haas School when Williamson won the Nobel and is now UC Berkeley’s Chief Innovation and Entrepreneurship Officer. “Yet for all of his intellectual creativity, I most often think of Olly as a person who lifts others. The ripple effects that he has had on his field through his students and colleagues could well be as large as the enormous impact his own work had.”

Williamson, the Edgar F. Kaiser Professor Emeritus of Business at Haas and Professor Emeritus of Economics and Law at UC Berkeley, received the most prestigious prize in economics in 2009 for his insights into what’s known as the “make or buy” decision. This is the process by which businesses choose whether to outsource a process, service, or manufacturing function or to perform the work in-house.

Williamson’s path-breaking contributions to economics were deep and boundary-spanning. They included seminal work that laid the foundation for the now-burgeoning fields of organizational and institutional economics. Traditional economic approaches of the early 1970s did not allow for analysis of governance within organizations. By showing that economics could illuminate the costs and tradeoffs that parties make in transactions, Williamson’s work brought governance and the management of relationships into economic theory.

His multidisciplinary approach to analyzing organizational structures was unconventional in economics at the time—he described it as a melding of soft social science with abstract economic theory. He looked not only at formal firm structure but at culture and social norms. Prof. Ernesto Dal Bó, the Phillips Girgich Professor of Business, called Williamson’s work “a fountain of vocation-shaping epiphanies.”

“After reading his work, we could no longer think of markets, organizations, and legal or political institutions in the same way. And so we didn’t,” Dal Bó said. “His insights are now part of the common sense of social scientists.”

Williamson’s theories gave rise to a new wave of empirical literature that tested his method of analysis in a wide range of industries, and shaped fields as diverse as public policy, law, strategy, and sociology. His “transaction cost” approach has since shed light on thinking about the design of joint ventures, long-term contracts, and bureaucracy more generally. His influence can be seen around the world, from electricity deregulation in California to investment in Eastern Europe to human resource management in the technology industry.

A simple analysis with broad reach

Oliver Eaton Williamson—known as “Olly” to his friends, colleagues, and students—was born in Superior, Wisconsin on September 27, 1932. The son of two teachers, he formed lifelong friendships with his Superior Central High School Class of 1950 classmates, holding four reunions per decade and annual poker weekends. He received his B.S. in management from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1955, an MBA from Stanford University in 1960 and a PhD from Carnegie Mellon University in 1963.

Williamson began his teaching career at Berkeley, where he was an assistant professor of economics in the undergraduate program. In 1965, he moved to the University of Pennsylvania, where he taught and held various leadership roles until he joined the faculty at Yale University in 1983.

Berkeley Haas Prof. Emeritus Pablo Spiller said that when Williamson recruited him to the economics department at Penn 40 years ago, “I didn’t realize that he was also recruiting me to his view of economics. The latter was done in subtle and not so subtle ways: his penetrating questions at seminars, written comments on papers, remarks in conversations, or over dinner,” he said. “While naturally a shy person, Olly was not shy to help a colleague see the light.”

Berkeley Haas Prof. Emeritus Pablo Spiller said that when Williamson recruited him to the economics department at Penn 40 years ago, “I didn’t realize that he was also recruiting me to his view of economics. The latter was done in subtle and not so subtle ways: his penetrating questions at seminars, written comments on papers, remarks in conversations, or over dinner,” he said. “While naturally a shy person, Olly was not shy to help a colleague see the light.”

In 1988, Berkeley lured Williamson back by appealing to his interdisciplinary interests and offering him appointments in not only business and economics but also the law. While at Berkeley, Williamson created a world-renowned PhD workshop known today as the Williamson Seminar on Institutional Analysis. He retired from teaching in 2004.

Williamson’s work on new ways of analyzing markets and business enterprises evolved from a paper written in 1937 by Ronald Coase, also a Nobel laureate. Building on Coase’s work, Williamson studied economic organization through the lens of transaction costs, exploring how different attributes of transactions were better suited to different types of organizations. It helped explain why some companies grow, creating management structures controlling different areas, while others remain independent.

“I originally thought of ‘make-or-buy’ as a stand-alone problem,” Williamson once said. “But now I think of it as being an exemplar. If you understand make-or-buy, which is a simple case, you can understand more complex cases.” These include joint ventures, labor contracts, antitrust, and industry privatization. Hundreds of economists and policymakers have since applied his framework to situations other than outsourcing, including the boundaries between public and private sector activity.

Path-breaking books

Williamson’s contributions to economics were widely recognized through awards, fellowships, and no fewer than 11 honorary doctorates from universities worldwide. Two of Williamson’s five books, Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications (1975) and The Economic Institutions of Capitalism: Firms, Markets, Relational Contracting (1985) are said to be among the most cited in the social sciences.

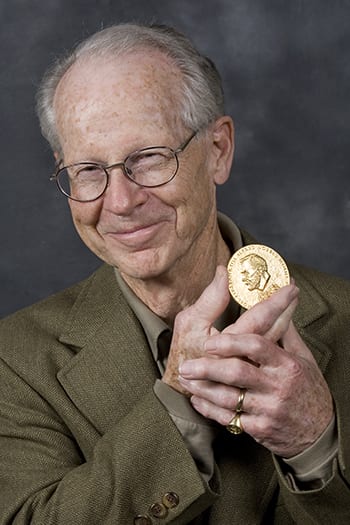

The Nobel Prize, which Williamson shared with political scientist Elinor Ostrom of Indiana University, marked the apogee of his career. The award—the second Nobel Prize for a Haas economist—came at the height of the global economic crisis. Many observers speculated that Williamson was selected for his work’s application to the financial meltdown and financial regulation. Those close to Williamson, however, said the honor was long overdue.

Prof. David Teece, the Thomas W. Tusher Professor in Global Business, predicted a Nobel for Williamson when he read a draft manuscript of Markets and Hierarchies as a University of Pennsylvania PhD student in 1974.

“I returned to his office three days later and reported, ‘This is a great book. Why has it taken me four years at Penn to discover a framework that addresses deep questions about the business firm and its organization?’” recalls Teece, noting that before Williamson, the economic frameworks and models to understand the business enterprise were “quite frankly pathetic.”

Teece went on to publish collection of essays in honor of Williamson’s book Markets and Hierarchies, entitled Firms, Markets and Hierarchies: The Transaction Cost Economics Perspective, with Glenn R. Carroll in 1999.

Prof. Steve Tadelis, the Sarin Chair in Leadership and Strategy, said Williamson’s work had heavily influenced him as a graduate student and assistant professor at Stanford. They had met and developed a collegial friendship by the time Tadelis joined Berkeley Haas in 2005, eventually authoring two papers together.

“Olly’s relentless drive for uncovering deep insights has always been an inspiration for me,” Tadelis said. “I will deeply miss his intellectual enthusiasm and friendly disposition, and at the same time I feel a deep gratitude for having him be a friend and mentor.

In recognizing Williamson and his work, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences singled out “his analysis of economic governance, especially the boundaries of the firm.”

In an interview upon learning he had won the prize, Williamson said. “All feasible forms of organization are flawed. We need to understand the trade-offs that are going on, the factors that are responsible for using one form of governance rather than another, the strengths and weaknesses that are associated with each of them.”

A passion for Berkeley

Throughout his life, Williamson displayed an uncommon humility even as his celebrity in economic circles grew. Just hours after his Nobel Prize was announced, Williamson was modest about his selection, calling it “undeserved” during a congratulatory toast with hundreds of Haas faculty, staff, and students.

Throughout his life, Williamson displayed an uncommon humility even as his celebrity in economic circles grew. Just hours after his Nobel Prize was announced, Williamson was modest about his selection, calling it “undeserved” during a congratulatory toast with hundreds of Haas faculty, staff, and students.

“I would describe myself,” he told the packed room, “as a conscientious teacher who had a lot of students who were tolerant and went on to do good work.”

Williamson was also passionate about Berkeley, calling it a “glorious place” whose commitment to excellence generates “extraordinary energy.” He donated a large portion of his Nobel Prize to Berkeley Haas to create a new endowed faculty chair in the economics of organization. (The Oliver E. and Dolores W. Williamson Chair of the Economics of Organizations is now held by Prof. John Morgan.)

The Haas School also established its highest faculty honor, the Williamson Award, in his name. Williamson was known for embodying the school’s Defining Leadership Principles—Question the Status Quo, Confidence Without Attitude, Students Always and Beyond Yourself.

“I can still hear a piece of advice he gave me when I first became dean that served me on many occasions: ‘When in doubt, decide on the merits,’ Lyons said. “With his own doctoral students, if they expressed doubt in themselves when taking the next step, he would tell them ‘I wouldn’t have suggested you try to do this if I didn’t have confidence that you could.’”

Williamson is survived by his five children and five grandchildren: son Scott (Susanna Krentz), daughter Tamara (Don Mohr), daughter Karen (Robert Indergand), son Oliver Jr. (Anna Suszanowicz), and son Dean (Mihoko Matsue); and grandchildren Kimberly and Kristin Indergand, Claire and Peter Williamson, and Erin Mohr. He was equally proud of his niece, Katherine Frisbie, and nephew, Steven Frisbie (Jennifer). He was predeceased by his wife of 55 years, Dolores Celini Williamson, in 2012.

A family memorial service will be held at a later time. Those wishing to remember Williamson may do so by making a donation to the Northern California and Northern Nevada Alzheimer’s Association.

Downloadable photos of Oliver Williamson are available here: https://haas.canto.com/v/oliverwilliamson

The Society for Institutional and Organizational Economics, which Williamson co-founded, will be posting a series of short essays honoring his contributions and life: https://www.sioe.org/news/passing-oliver-williamson.

Posted in:

Topics: