Topic: Business & Public Policy

Is it ethical? New undergrad class trains students to think critically about artificial intelligence

“Classified” is an occasional series spotlighting some of the more powerful lessons being taught in classrooms around Haas.

On a recent Monday afternoon, Sohan Dhanesh, BS 24, joined a team of students to consider whether startup Moneytree is using machine learning ethically to determine credit worthiness among its customers.

After reading the case, Dhanesh, one of 54 undergraduates enrolled in a new Berkeley Haas course called Responsible AI Innovation & Management, said he was concerned by Moneytree’s unlimited access to users’ phone data, and whether customers even know what data the company is tapping to inform its credit scoring algorithm. Accountability is also an issue, since Silicon Valley-based Moneytree’s customers live in India and Africa, he said.

“Credit is a huge thing, and whether it’s given to a person or not has a huge impact on their life,” Dhanesh said. “If this credit card [algorithm] is biased against me, it will affect my quality of life.”

Dhanesh, who came into the class believing that he didn’t support guardrails for AI companies, says he’s surprised by how his opinions have changed about regulation. That he isn’t playing Devil’s advocate, he said, is due to the eye-opening data, cases, and readings provided by Lecturer Genevieve Smith.

A contentious debate

Smith, who is also the founding co-director of the Responsible & Equitable AI Initiative at the Berkeley AI Research Lab and former associate director of the Berkeley Haas Center for Equity, Gender, & Leadership, created the course with an aim to teach students both sides of the AI debate.

Her goal is to train aspiring leaders to think critically about artificial intelligence and implement strategies for responsible AI innovation and management. “While AI can carry immense opportunities, it also poses immense risks to both society and business linked to pervasive issues of bias and discrimination, data privacy violations, and more,” Smith said. “Given the current state of the AI landscape and its expected global growth, profit potential, and impact, it is imperative that aspiring business leaders understand responsible AI innovation and management.”

“While AI can carry immense opportunities, it also poses immense risks to both society and business linked to pervasive issues of bias and discrimination, data privacy violations, and more,” – Genevieve Smith.

During the semester, Smith covers the business and economic potential of AI to boost productivity and efficiency. But she also explores the immense potential for harm, such as the risk of embedding inequality or infringing on human rights; amplifying misinformation and a lack of transparency, and impacting the future of work and climate.

Smith said she expects all of her students will interact with AI as they launch careers, particularly in entrepreneurship and tech. To that end, the class prepares them to articulate what “responsible AI” means and understand and define ethical AI principles, design, and management approaches.

Learning through mini-cases

Today, Smith kicked off class with a review of the day’s AI headlines, showing an interview with OpenAI’s CTO Mira Murati, who was asked where the company gets its training data for Sora, OpenAI’s new generative AI model that creates realistic video using text. Murati contended that the company used publicly available data to train Sora but didn’t provide any details in the interview. Smith asks the students what they thought about her answer, noting the “huge issue” with a lack of transparency on training data, as well as copyright and consent implications.

After, Smith introduced the topic of “AI for good” before the students split into groups to act as responsible AI advisors to three startups, described in three mini cases for Moneytree, HealthNow, and MyWeather. They worked to answer Smith’s questions: “What concerns do you have? What questions would you ask? And what recommendations might you provide?” The teams explored these questions across five core responsible AI principles, including privacy, fairness, and accountability.

Julianna De Paula, BS 24, whose team was assigned to read about Moneytree, asked if the company had adequately addressed the potential for bias when approving customers for credit (about 60% of loans in East Africa go to men, and 70% of loans in India go to men, the case noted), and whether the app’s users are giving clear consent for their data when they download it.

Other student teams considered HealthNow, a chatbot that provides health care guidance, but with better performance for men and English speakers; and MyWeather, an app developed for livestock herders by a telecommunications firm in Nairobi, Kenya, that uses weather data from a real-time weather information service provider.

The class found problems with both startups, pointing out the potential for a chatbot to misdiagnose conditions (“Can a doctor be called as a backup?” one student asked), and the possibility that MyWeather’s dependence on a partner vendor could lead to inaccurate climate data.

Preparing future leaders

Throughout the semester, students will go on to develop a responsible AI strategy for a real or fictitious company. They are also encouraged to work with ChatGPT and other generative AI language tools. (One assignment asked them to critique ChatGPT’s own response to a question of bias in generative AI.) Students also get a window into real-world AI use and experiences through guest speakers from Google, Mozilla, Partnership on AI, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and others.

All of the students participate in at least one debate, taking sides on topics that include whether university students should be able to use ChatGPT or other generative AI language tools for school; if the OpenAI board of directors was right to fire Sam Altman; and if government regulation of AI technologies stifles innovation and should be limited.

Smith, who has done her share of research into gender and AI, also recommended many readings for the class, including “Data Feminism” by MIT Associate Professor Catherine D’Ignazio and Emory University Professor Lauren Klein; “Unmasking AI: My Mission to Protect What Is Human in a World of Machines” by AI researcher, artist, and advocate Joy Buolamwini; “Weapons of Math Destruction” by algorithmic auditor Cathy O’Neil; and “Your Face Belongs to Us” by New York Times reporter Kashmir Hill.

Smith said she hopes that her course will enable future business leaders to be more responsible stewards and managers of such technologies. “Many people think that making sure AI is ‘responsible’ is a technology task that should be left to data scientists and engineers,” she said. “The reality is, business managers and leaders have a critical role to play as they inform the priorities and values that are embedded into how AI technology is developed and used.”

Berkeley City Council Candidate James Chang, MBA 24, talks People’s Park, campus safety

James Chang, Chief of Staff for Berkeley City Councilmember Ben Bartlett, thought he’d return to a private sector job after graduating from the Berkeley Haas Evening & Weekend MBA Program this spring.

Turns out that’s not happening just yet.

Chang said his experiences in the MBA program inspired him to double down on his leadership skills and remain in the public sector, running for the open District 7 City Council seat in the April 16 special election. District 7 stretches from the UC Berkeley campus to five blocks south. Chang is running against UC Berkeley senior Cecilia Lunaparra.

Haas News recently talked to Chang, who also holds a bachelor’s degree in political economy from UC Berkeley, about his love of public service, his experiences at Haas, and his desire to serve Berkeley in a district where students make up the majority of the voting population.

You came to Haas planning to return to the private sector. Why did you change your mind and run for office instead?

I wanted to leave politics. But coming here renewed my passion for public service. I was a delegate in the Graduate Assembly, representing all three Haas MBA programs, and president of the EWMBAA (student) association. That is what made me realize that I want to really double down on public service.

As you approach graduation, what are some highlights from your time spent in the MBA program?

Taking core classes with my cohort and the deep friendships that you build. Also, placing second at the HUD Innovation in Affordable Housing Student Design and Planning Competition. Being able to work with different people from the Real Estate development program, Berkeley Law, and the architecture program at Berkeley… If there’s anything I could recommend that Haasies do, it is case competitions with people from outside of your program. Meeting people from different majors and different walks of life is a beautiful thing.

What made you decide to run for a seat on the City Council?

I’m running because I have a deep passion for public service and because I have a deep love for Berkeley. Berkeley is a place where I found the love of my life, Richard. But it goes a little deeper than that. I get to be authentically “me” here, whether that’s showing up at work at City Hall, or showing up authentically at Haas—being a leader on campus representing Haas, I have the opportunity to be who I am: fearless, not just in my identity, but also in my values and being able to speak up, even if it’s sometimes unpopular.

What are the core issues driving your campaign?

Fighting for affordable housing. I am concerned about housing affordability and availability and safety, which I know is a big concern for many of our students. Students deserve a nice place to live and an economically vibrant Telegraph Avenue business district. These are all things that I’m running on. The person who represents you—the job is to really serve you and bring back resources to the community, to make the community better, and I think I’ve shown I’ve been able to do that.

Do you support the UC Berkeley campus decision to build housing at People’s Park?

Yes. I think this is one of the reasons why Haasies should care about this election. The building project at People’s Park, to be clear, includes two-thirds green space. There’ll be housing for 1,100 students, and there will be over 100 housing units for the unhoused. We can either have that as an option, or an open-air drug market as the alternative. I know students overwhelmingly want housing. I think a lot of students are too afraid to speak up because, anytime we do anything to solve a problem that requires some form of public safety measure, it’s often vilified as a right-wing tactic or supporting right-wing policies. And I just really reject those notions.

We can either have that as an option, or an open-air drug market as the alternative. I know students overwhelmingly want housing.

How do you think your classes and community at Haas have helped you to be a better leader?

I think that all of my classes are founded on our Haas Defining Leadership Principles. Whether that’s going beyond ourselves, questioning the status quo, confidence without attitude, or students always, every single one of my classes has really grounded me. I have become a better leader, am open to different perspectives, ask the tough questions, and also just always want to learn and soak up different knowledge. I always say Haas is one of the most supportive communities that I’ve ever belonged in.

What do you love about your current job?

What I do best is I know how to deliver for constituents who are in need, as long as they’re patient with me and give me time. Most of the time, I am able to give them what they want within reason, whether that’s cleaning up a street, making sure that our unhoused people are compassionately served, or getting a traffic circle at the edge of our district, or making sure that their events get fully funded. Also, getting $9 million for the African American Holistic Research Center, and making MLK Way much safer. It’s still messy, but safe. That took seven years, and I am so proud of it.

How would you make this area of Berkeley safer?

I think we need better lighting on and off campus. The campus “Warn Me” system needs to be a lot better. The city could do more to make sure that simple things like cracked shop windows are fixed, simple things like cleaner streets—this goes a long way. We are also working with merchants to install private cameras that work with the city. I am open to public cameras but I am always concerned with civil liberties, so I’m not ready to say yes or no to that. We should be working with business first. One of my biggest goals is economic growth on Telegraph. We know the No. 1 crime deterrent is more eyes on the streets, so that’s what I’m really hoping for.

The special election will be held April 16 until 8 p.m. (mail-in ballots have been sent). Registration has ended, but eligible District 7 voters can register at the voting location, the YWCA Berkeley, 2600 Bancroft Way, Berkeley, before and on election day.

What critics of American higher education get wrong

(In)justice and populism

How To Get a Corporate Parent That Is Better For Business

What’s missing for German startups?

A Legacy of Impact : Student Reflections on the Career of Chip Bergh, Former CEO of Levi Strauss & Co.

Now is the time to put people before robots

The Great Remobilization – A Review

What’s age got to do with it? 76-year-old MBA student “having the time of my life”

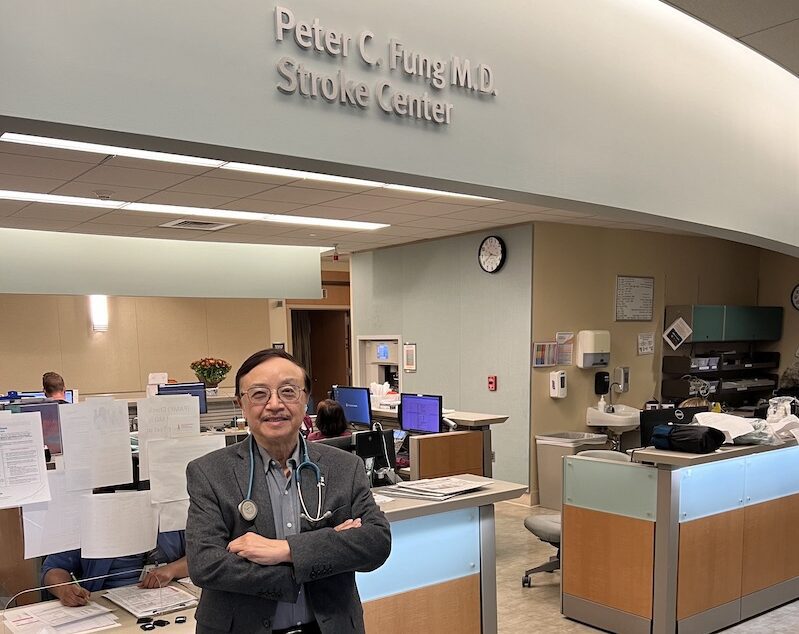

At a time of life when many of his peers are well into retirement, Peter C. Fung is having “the time of his life” as a student in the Berkeley Haas Executive MBA Program.

But for Fung, 76, a retired neurologist and self-proclaimed lifelong learner, retirement was never an option. It’s the reason he wanted to earn an MBA and why he connected immediately to Students Always, one of the four Haas Defining Leadership Principles (DLP).

“Age is not important,” said Fung, EMBA 24, who sits on the El Camino Health District Board of Directors and for a decade led the hospital’s stroke program, which is named after him. “When we’re using our brains in thinking or learning new information, neuronal pathways from neuron to neuron are formed. This is the best anti-aging therapy. Just like an old car, you have to keep it running to keep it from rusting.”

Developing leadership skills

As a physician, Fung, an advocate for health, wellness, and disease prevention, has spent more than 35 years improving health care quality and access. Now, he’s running for an open seat on the Santa Clara Board of Supervisors, where he hopes to tap what he’s learned at Haas on the journey.

In the EMBA program, Fung said he’s developed leadership skills that he believes will help him stand out as a political candidate. He’s also gained new expertise in economics and data analysis—and a deeper understanding of organizational finance that he hopes to apply to overseeing the county’s budget and tackling the deficit.

He said he is impressed that his classmates—busy with careers and young families—are all committed to learning new skills, pivoting to new jobs, starting companies, and helping each other.

“The cohort has been treating me as one of their own,” he said. “I was terrible with the computer, especially with Excel, when I started the program. But I was finally able to master this very powerful tool. I actually did quite well on my finals. I have enjoyed the challenge. It was a thrill.”

Fung believes he brings something unique to the program. His classmates agree.

Abdus Sattar, EMBA 24, collaborated with Fung during a recent business policy immersion trip the cohort took to Washington D.C. Their paper on “Medicare Drug Price Negotiation, “offered me an opportunity to delve into crucial healthcare topics,” said Sattar, who holds a PhD in electrical engineering.

Saya Honda, EMBA 24, said that Fung “pushes us and encourages us to challenge ourselves.” She said Fung embodies all four of the Haas Defining Leadership Principles: He questions the status quo by being unafraid to ask questions; he shows confidence without attitude by using humor in public speaking; he’s a student always as the oldest person in the cohort and as someone who believes in the importance of education; and he’s questioning the status quo by running for county supervisor.

A passion for learning

Originally from China and having grown up in Hong Kong, Fung came to the United States to study at the University of Michigan Medical School, where he became board-certified in internal medicine and neurology and also earned a master’s degree in neurochemistry and neuropharmacology.

“His passion for learning is not only impressive but also infectious,” said Elizabeth Stanners, executive director of the Haas Executive MBA program.

When a professor recommended a PhD program, Fung’s wife, who missed living in Asia and warmer weather, balked. “She said, ‘We’re going to move to California.’ he said. “That pretty much was an ultimatum. So we came to San Jose, where I was the only neurologist in my area of the city.”

For Fung, 1996 proved a turning point in life after his mother had a devastating stroke that left her paralyzed on one side and unable to speak. Fung managed to consult with the chief of the stroke program at Stanford about a new drug called tPA, which his mother received. “The next day, she asked, ‘Why am I here?’ Her arm was no longer paralyzed, and she was speaking fluently,” Fung recalled.

Running for supervisor

After that experience, Fung decided to study strokes, immersing himself in articles and at conferences for a decade. Along the way, he became the first physician in the Bay Area to be board-certified in stroke neurology. “I thought I would work as a stroke and vascular neurologist for the rest of my life,” he said. “But then, I started thinking about what else I could do.”

Running for office was part of that plan, to expand his commitment to improving access to care for everyone. Earlier in his career, Fung served as co-director of the El Camino Health Chinese Health Initiative, to provide education and access to the Asian community. The initiative is now the largest nonprofit organization catering to Chinese patients in California.

In 2014, he ran for the El Camino Healthcare District, which manages the budget for the district’s hospitals. The Santa Clara Board of Supervisors is the next step, where his work would have impact on a larger population.

If elected, he said he’d tap into the DLPs to help with decision making in critical areas that are top of mind for constituents: crime, safety, healthcare, inflation, education, and housing. “After thorough research and analysis, I would delve deeply into the issues at hand, engaging with fellow political leaders to gain diverse perspectives, and to develop well-informed and practical solutions,” he said.

Meanwhile, Fung is looking forward to adding an MBA to a long list of accomplishments.

“If I’m the oldest student to graduate successfully from Haas, and I go on to make a meaningful life after graduation, that will be something to write about,” he said. “That’s my goal.”

Boeing 737 Max 9 flights cleared for takeoff

AI explained: The majority of the population in the U.S. wants regulation

Study reveals a hidden channel for political influence

Institutional ownership of U.S. corporations has increased ten-fold since 1950. New research from Haas shows this trend has political implications.

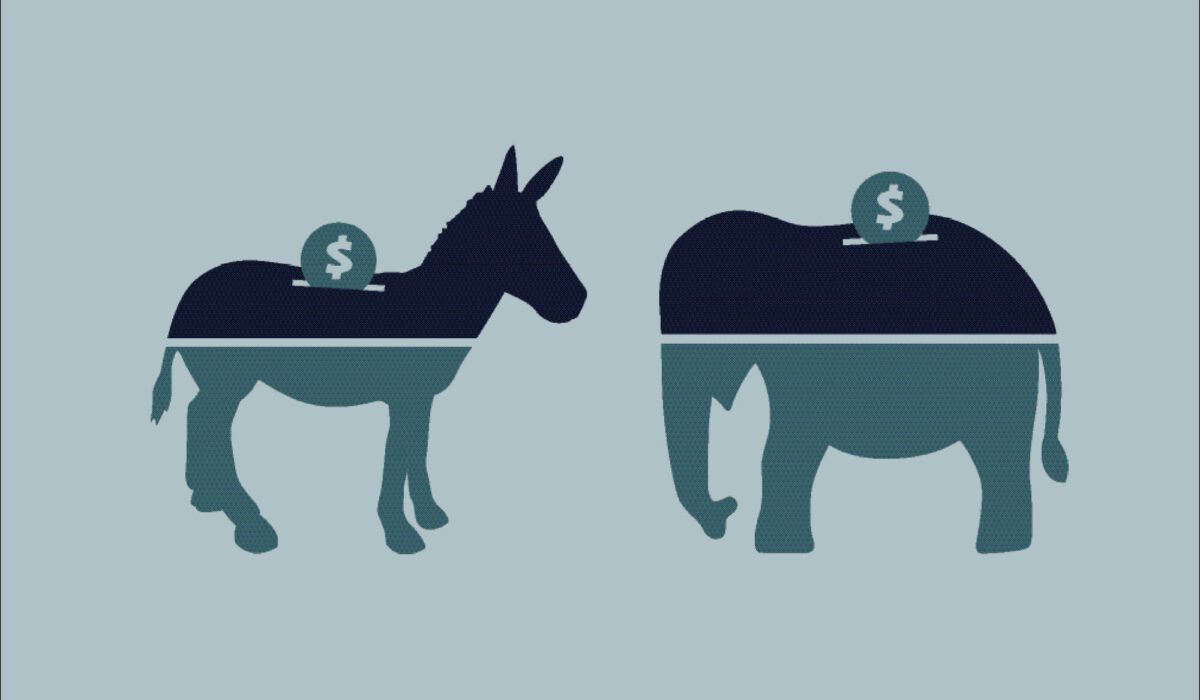

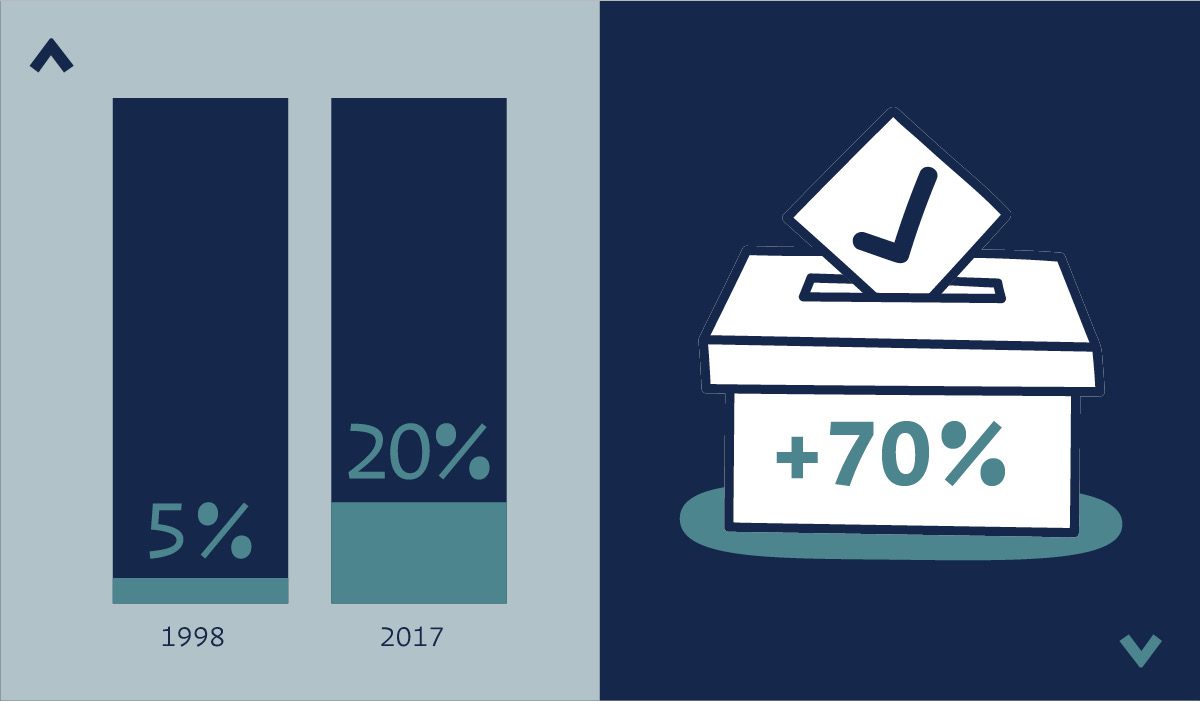

The finance world has witnessed extensive consolidation over the past several decades. Institutional investors owned just 6% of publicly traded U.S. companies in 1950; in 2017, they owned 65%. The “big three” of BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street Global Investors held 5% of S&P 500 shares in 1998 and more than 20% by 2017.

For Matilde Bombardini, an associate professor at Berkeley Haas who has spent her career studying political influence, this trend raised a novel question. “If this is a phenomenon in the financial markets, where institutional investors are controlling increasingly large shares of the landscape, maybe there are also political implications,” she says. “Does this concentration in ownership translate into concentration in the so-called political market?”

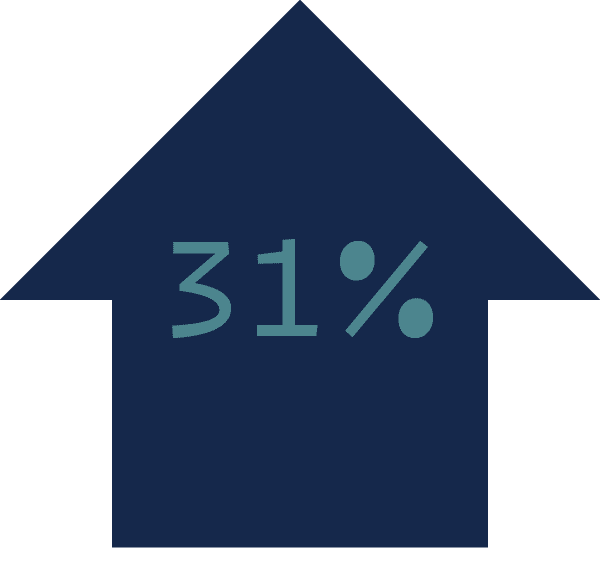

The answer, she shows in a recent co-authored National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, appears to be yes. The researchers, who include Francesco Trebbi of Berkeley Haas, Marianne Bertrand of the University of Chicago, Raymond Fisman of Boston University, and Eyüb Yegen of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, looked at the connection between institutional ownership and political contributions. They found that political giving shifts following a large acquisition: For newly acquired firms, the correlation in giving to politicians favored by the investor increases by up to 70%.

“Following this one event, campaign contributions start moving closer together, in a sense,” Bombardini says. “These acquired firms start giving to politicians that the institutional investor gives to.”

Acquisitions and influence

The researchers collected data on investors that manage over $100 million in assets and on portfolio firms in which these investors have holdings. (The dataset covers the years 1980 to 2018.) They looked specifically at moments when an investor acquired 1% or more of the outstanding shares of a given portfolio firm.

In tandem, they matched names of investors and portfolio firms to their political action committees (PACs) using data from the Federal Election Commission. These PACs—574 connected with investors, 2,456 with portfolio firms—could in turn be connected to campaign contributions to specific candidates.

They found that large acquisitions were accompanied with a significant movement in giving toward the investors’ favored PACs, with the correlation between investor and portfolio firm increasing by 30% to 70%. The researchers noted that this realignment in donations comes at a time when giving, in general, is on the rise: Investment firms increased political expenditures by nearly a factor of six between 1980 and 2018. This trend implies that more money is coming from a smaller number of voices.

“Of course, one interpretation could be that investors acquire companies that are already like them, so the causation goes the other way,” Bombardini says. To test this interpretation, the researchers looked specifically at index funds, which make their acquisitions in order to replicate an index, like the S&P 500. That means these purchases were required at a specific and unplanned moment, so they are unlikely to be the result of political strategy or like-mindedness.

“We zero in on these kinds of acquisitions that are more random and still find the effect,” Bombardini says. “That helps alleviate the concern over causality.” They also found that the change in giving was driven primarily by portfolio firms moving toward investors and not the other way around.

Tough to regulate

Alongside the political implications, Bombardini and her colleagues describe potential trouble that these results raise for the realm of corporate governance. If portfolio firms are subtly nudged by their investors to contribute to politicians or political issues that are not directly tied to their business, that could derail profit maximization.

“These firms might just keep adding politicians to their roster that are not germane to their business,” Bombardini says. “So, you have a case of misaligned incentives.”

She emphasized that these types political donations would not be the result of explicit pressure from investors. Rather, they would be the result of an implicit understanding that by giving to preferred political candidates a firm could receive favorable treatment down the road.

But for Bombardini, the concerns over democracy are graver. For one, she wonders, does this soft influence show up in other domains? Are these same trends visible in lobbying dollars, or charitable giving, based on the concentrated heft of institutional investors? Perhaps more urgently, how might this subtle avenue of influence be reined in?

“Federal law is very clear on the fact that you cannot make political donations on behalf of someone else, but it’s not likely that the investor is asking the portfolio firm to donate,” Bombardini sayd. “This kind of quieter influence is hard to regulate, but we should at least be aware that this concentration of influence is happening. It should bring us back to the general questions that surround regulating campaign contributions.”

California leads the way on climate

No train, (because of) no gain? Under-training by employers in spot labor markets: Guest post by Nicholas Swanson

Under the Influence

How institutional investing dictates politics

In 1950, institutional investors—such as mutual funds, pensions, and insurance companies—owned roughly 6% of publicly traded companies. In 2017, that figure was 65%. Such a dramatic increase raises many questions but central among them for Associate Professor Matilde Bombardini is what it implies for the function of American politics—even American democracy.

In 1950, institutional investors—such as mutual funds, pensions, and insurance companies—owned roughly 6% of publicly traded companies. In 2017, that figure was 65%. Such a dramatic increase raises many questions but central among them for Associate Professor Matilde Bombardini is what it implies for the function of American politics—even American democracy.

“By controlling large equity shares in many companies, institutional investors can potentially affect the political orientation of the firms they invest in,” Bombardini says.

With colleagues from Haas, the University of Chicago, Boston University, and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Bombardini monitored the connection between an investor’s acquisition of a large stake in a portfolio firm and subsequent donations by the firm’s political action committee. The researchers found that when a firm is acquired by an investor, it shifts its PAC giving to more closely mirror that of the new investor. This political shift is more pronounced when a highly partisan investor is involved or when somebody from the investment side assumes a seat on the board of the portfolio firm. “Whether this is dictated by the investor or simply understood by the firm as a way to align with the investor, it has the potential to lead to more concentration of political influence,” Bombardini says.

These findings suggest a need to more carefully interrogate the governance role of institutional investors. Beyond that, they reveal the diffuse and largely invisible amplification of political influence afforded a small collection of fund managers.

“Although we’ve shown that much of corporate political giving can be rationalized by profit maximization,” Bombardini says, “this study reveals that perhaps firms’ giving also reflects the political preferences of some of their shareholders.”

The “Big Three” of BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street Global Investors held more than 20% of S&P 500 shares in 2017 as compared to 5% in 1998.

Political giving often shifts after an acquisition. The probability of a portfolio firm giving to a particular congressional district increases by up to 70% after a large acquisition by an investor that also gives to that congressional district.

31% Increase in the probability that a firm’s PAC will donate to a politician supported by an investor’s PAC after an acquisition.

When an investor obtains a seat on the portfolio company’s board after an acquisition, the effect on political donations is more than three times that of an acquisition alone. Investors attained board seats in about 5% of the companies studied. (Sample includes 2,456 firms.)