House Arrest

Silicon Valley has reigned as the epicenter of innovative companies and venture capital fortune for some 30 years. But over the last decade, other cities have sought the economic benefits (and bragging rights) of spawning their own high-tech hubs.

Nationwide, places like New York, Boston, Austin, and Seattle have built infrastructures for home-grown startups and venture capitalists, putting Silicon Valley on notice that it was no longer the only game in town. Worldwide locales have also developed their own innovation ecosystems, exploiting a variety of natural resources to their advantage.

Some, like Lebanon and Guatemala, have grown from excellent educational systems; others, such as Puerto Rico and Singapore, have benefitted from a strategic location and government support. Israel’s tech sector has risen from its military intelligence, while Nigeria has captured its vibrant youth culture. And some places, like New Zealand, just think different.

And behind the rise to prominence of all of these global locations are Haas alumni taking their firsthand experience of the dynamic Bay Area and reproducing it elsewhere.

These alumni have not only gone beyond themselves to create social impact, they’ve spread prosperity and championed ingenuity around the world. Read their stories…

Lebanon: Startup Oasis

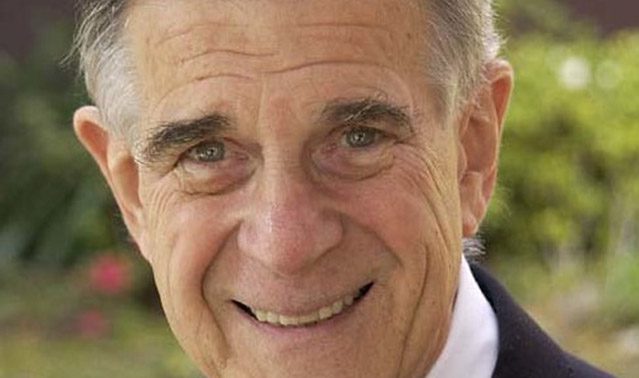

In less than a decade, the Speed Accelerator has transformed Beirut into a hotbed for high tech

Sami Abou Saab, MBA 12 (shown above), always planned on returning to his native Lebanon to help launch technology companies. So when the time came five years ago to leave a cushy job as a global product manager at Skype to take a chance on Lebanon’s burgeoning startup scene, he didn’t hesitate. “I wanted to be in the driver’s seat and make an impact whatever the risk—either I make it and it’s successful, or if I fail, at least I tried,” he says. He’s succeeded as CEO of Speed Accelerator, a Beirut-based startup accelerator that’s launched 42 companies that have collectively raised $4.6 million in early stage capital.

Speed Accelerator has benefitted from two local initiatives: a private real estate company launching the Beirut Digital District, which subsidized rent for Speed’s facilities, and Lebanon’s Central Bank injecting some $400 million (later $650 million) into the country’s knowledge economy. The latter provided indirect (via venture capitalists) and direct funding for Speed Accelerator. In many ways, the country is ripe for creative innovators—offering year-round perfect weather, a cosmopolitan lifestyle with great food and nightlife, and a record influx of some 2 million tourists each year. What sets it apart though, says Abou Saab, is its educational system. Beirut has 50 universities, including the American University of Beirut (arguably the best in the Middle East), where Abou Saab studied engineering.

Abou Saab’s accelerator capitalizes on that technical talent by giving companies a $30,000 cash injection along with workshops on product development, marketing, sales, and team building in exchange for 5% equity. Thanks to its pitching practice, Speed’s startups have won all the major competitions in the region.

Among Speed’s successes are Synkers, a marketplace to connect students to tutors, which has cornered the market in Lebanon and expanded to the United Arab Emirates; and Neotic, a machine-learning algorithm to help investors plan their stock picks, which has beaten the market by 20% over the last two years. Recently, Speed announced a partnership with world-leading accelerator Techstars to further expand the reach of its companies and the presence of Lebanon on the entrepreneurial map.

For Abou Saab, it’s all a dream come true. “Here I am five years later,” he says, “still as excited as the first day.”

Guatemala: Power of Place

A unique real estate hub helps spawn a Latin American Silicon Valley

GUATEMALA

Juan Mini

MBA 99

Photo: Jordi Ruiz Cirera

Throughout his life, Juan Mini, MBA 99, has vacillated between a career in technology and working in the family business, a third-generation real estate and civil engineering firm based in Guatemala City. Now, he’s found a way to do both—as founder of Campus Tecnológico, a physical hub for innovation in the heart of the city. Founded in 2009, the development has grown from one small building with 40 technology companies to three buildings with over 200, arguably the biggest tech hub in Latin America.

The campus builds off of Guatemala’s strength in software development, a strong educational system, business-friendly legal system, and proximity to the U.S. In addition to providing space, Mini also offers coding courses, networking events, and mentorship programs.

After earning engineering degrees at Cornell and Stanford, Mini designed Mac components at Apple. “I fell in love with the whole Silicon Valley concept,” he says. He worked in biotech, then again at the family business, before entering Haas.

Mini then joined forces with Scott Kucirek, MBA 99, to found online real estate company ZipRealty, which grew to be the nation’s fifth-largest broker. After taking ZipRealty public in 2004, Mini grew homesick. At the time, the software industry was dispersed throughout Guatemala City. “One thing I learned in Silicon Valley is that to be successful in technology, everyone has to be together, and you have to have the ingredients to grow,” he says. Campus Tecnológico was born.

Among its success stories is BlueKite, a webbased platform for sending money between countries—crucial for many migrants working overseas. Acquired by Paypal, it now has 200 programmers. Another firm, Aerobots, creates drones for agribusiness in Central and South America.

Mini hopes to add two more buildings to the campus in the next decade. He’s also planning a satellite Campus Tec in Miami by year’s end, to serve as a bridge to U.S. and Mexican markets. After importing the Silicon Valley concept to Guatemala, he’s exporting it back.

Israel: Military Intelligence

Innovation from Israel’s elite army units have made it a worldwide leader in entrepreneurship

ISRAEL

Gonzalo Martínez de Azagra

MBA 10

Photo: Corinna Kern

There’s a secret to the success of Israel’s startup sector, says venture capitalist Gonzalo Martínez de Azagra, MBA 10: mandatory military service. “I don’t know what you were doing in your 20s, but I was definitely not leading a hundred people in lifeor- death situations,” says M. de Azagra, originally from Spain. “For them, becoming an entrepreneur doesn’t seem risky.”

Israeli startups often stem from the elite military units where the brightest are singled out for technical and leadership training, M. de Azagra says, with companies focusing on cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, and big data. Centered in Tel Aviv and the nearby suburb of Herzliya, the tech sector also benefits from the country’s small size and tight-knit networks. “You are always within one level of the right person,” he says. “It makes it very collaborative, and things happen fast.” By all accounts, Israel leads the world in venture capital investment per capita, at a rate about twice the amount of the U.S.

M. de Azagra first started investing in companies here as head of Samsung Ventures Israel in 2012. In five years, he completed more deals than any other VC, deploying $120 million with a three times return on investment. In 2017, he co-launched his own $60 million fund, Cardumen Capital, funded by several C-level executives and partnerships with banks and utility companies in Spain and Latin America, focusing on B2B companies with a unique technology advantage.

Several of his successful investments are in the realm of computer vision, an offshoot of artificial intelligence that M. de Azagra himself studied in engineering school. They include Corephotonics, which makes the multilens cameras for iPhones; PrimeSense, which makes the iPhone’s front-facing selfie cameras; and Replay, which reconstructs 3D images from cameras around sports stadiums.

“We’re looking for companies with a distinct advantage in technology, rather than just an innovative business model, which might be more typical in the U.S. or Europe,” M. de Azagra says. “From day one, they are thinking about competing on a global scale.”

Puerto Rico: Rapid Recovery

Puerto Rico is bouncing back with a passionate startup culture, bridging the U.S. and Latin America

PUERTO RICO

Jennifer Hopp

MBA 08

Photo: Angel Valentin

Venture capitalist Jennifer Hopp, MBA 08, knew almost nothing about Puerto Rico five years ago. Invited to the island territory to serve as a mentor at startup accelerator Parallel 18, she fell for the people. Even the devastation wrought by Hurricane Maria in 2017 couldn’t deter her from moving there.

In the hurricane’s wake, a vibrant entrepreneurial sector has grown in San Juan, remaking the capital city. Dozens of accelerators and co-working spaces have opened. What’s lacking, however, is capital. So Hopp started ATO Ventures, a firm focusing on pre-revenue investments, mitigating risk by helping companies with market discovery and validation before launch.

In Puerto Rico, Hopp has found driven and passionate entrepreneurs without the attitude of Silicon Valley. “Capital is harder to come by here, so there is more focus on profitability,” she says. Add in zero capital gains taxes, extremely low corporate taxes, cheaper labor, and a lower cost of living than the U.S., and Puerto Rico has become an important bridge between Latin America and North America. “It’s a bilingual, bicultural community,” she says. “Things flow easily back and forth.”

Hopp started her fund with $3 million (and climbing), aiming to make investments of $250,000 and attract follow-on funding. ATO’s first venture is iSono Health, a portable device for early breast cancer detection. Hopp has high hopes for Puerto Rico. “It will become one of the greatest global innovation hubs of our time,” she says.

Singapore: Gateway to Asia

When it comes to developing innovative businesses, Singapore is a springboard to opportunity

SINGAPORE

Pin Chin Kwok, MBA 09

Stefan Jacob, MBA 10

Photo: Lauryn Ishak

When Pin Chin Kwok, MBA 09, and Stefan Jacob, MBA 10, met at Haas, they had come from different career paths—her from banking, him from consulting—but they had a common goal: to create social impact through business.

It was no accident that after graduation they ended up in Kwok’s native Singapore. The island city-state has emerged as the central hub for business innovation and technology in Asia, sandwiched between the major markets of India, China, and Indonesia and boasting a business- friendly atmosphere welcoming to foreigners and venture capitalists. “Singapore is ahead of the game with the best infrastructure and the greatest concentration of talent,” says Jacob. “It’s always trying to reinvent itself.”

When the couple first arrived, they created a social enterprise called BOPHub—an acronym for “base of the pyramid.” The organization helps small social startups that are providing access to resources such as clean water, off-grid energy, and cook stoves for impoverished communities find funding and scale operations. “The concept of social enterprise was nonexistent in Singapore when we got here,” Jacob says. The organization still exists, now occupying a 65,000-square-foot space in the city, though Kwok and Jacob have moved on to other forms of impact, staying at the forefront of Singapore’s entrepreneurial evolution.

The government has poured money into creating hubs for biotech and other industries, and more recently launched regulatory sandboxes in health tech, insurance tech, and fintech to spur innovation.

Jacob worked for Coca-Cola’s innovation program, eventually spinning out a startup called Savasti, an app to help mom-and-pop retailers in Asia with last-mile distribution and ordering. He now works for Liberty Mutual, heading up Solaria Labs to focus on innovating customer engagement in insurance.

Kwok, meanwhile, worked on healthcare innovation with Medtronic and LumenLab before leading business in Asia for the Silicon Valley startup Savonix, which is producing a new platform for the early screening of dementia. She’s been working with private insurance organizations, brain health companies, and governments to integrate the screening platform in Asia. “We know we have the power to change the course of this disease,” Kwok says.

New Zealand: Natural Wonder

Geographic remoteness allows for cutting-edge thinking in New Zealand

NEW ZEALAND

Simon Wakeman, PhD 07

with his wife, Rachel Fleet, MBA 04

Photo: Daniel Mahon

New Zealand’s isolated location makes it ripe for idea generation, says Simon Wakeman, PhD 07, an advisor to the New Zealand Government on innovation policy at the country’s Ministry for Business, Innovation, and Employment. “Although it’s a problem being a long way from markets, it’s actually quite a good place to do cutting-edge technology development,” he says. “People come up with unique ways of doing things.”

Flying-car company Wisk, for example, is testing electric “air taxis” that will hover 10 meters above the ground. The company has signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the New Zealand government, attracted by the Civil Aviation Authority’s relatively friendly attitude toward unmanned aerial vehicles. “Having a single level of government makes it much more flexible in getting laws changed to make new industries work,” explains Wakeman, a native Kiwi.

Technology is the third-largest industry in the country, with startups focusing on everything from cryptocurrency to bionic devices to autonomous harvesting equipment. Wakeman, building on his doctoral work focused on commercializing biotech research in the pharmaceutical sector, has been involved in strengthening relationships between universities and industry, including a new technology incubator program to enable more rapid commercialization of innovative research. “It’s all about getting research institutions and the startup community to speak better to each other,” he says.

Nigeria: Getting in Tune

Tapping into a vibrant metropolis to improve educational opportunities

NIGERIA

Joshua Ahazie

BS 18

Photo: Andrew Esiebo

Growing up in Lagos, Nigeria, Joshua Ahazie, BS 18, was singing and playing jazz piano from a young age and has always been obsessed with music. An early business venture sold online rare African vinyl from legendary record shop Lagos Jazzhole. A song from one of those records inspired the name for his social enterprise, ATIDE, which means “We Are Here” in Yoruba.

Launched in April 2018, ATIDE started as an e-commerce platform for Nigerian artists and entrepreneurs to sell their work internationally. So far, Ahazie has signed a photographer, fashion designer, and several streetwear artists. The company donates 25% of each sale to their social impact fund which has helped three local schools with new books, furniture, and renovations, impacting 1,100 children in Lagos.

Ahazie developed his business model at Haas, where every class became fodder for practical learning. “From leadership to accounting to economics, everything I learned I use on a day-to-day basis,” he says. He now shares what he’s learned with another wing of the company, atideSTUDIOS, a marketing agency started last summer specializing in strategy development, design, and video production for companies in Lagos’ burgeoning startup scene. So far, the company has worked with seven clients across the music, entertainment, tech, and restaurant industries, with profits supporting his other endeavors.

With its bustling cultural scene and entrepreneurial spirit, Lagos has become the largest startup ecosystem in Africa. A profusion of fintech and other tech companies have clustered there and in nearby Yaba, known alternately as Yabacon Valley or Silicon Lagoon. Ahazie attributes that growth to a “youth bulge,” with nearly half the country’s population under age 15, together with the lack of employment in traditional industries. “Everyone has a side hustle; they go to work then work on their small business,” Ahazie says. “Our people are showing a variety of ways to thrive in today’s fast-changing world.”

Posted in:

Topics: