Berkeley Haas’ commitment to educating future-oriented leaders demands a constant evolution of our teaching and research. Here, we highlight two new research centers whose work will keep Haas at the forefront of behavioral economics and drive positive healthcare innovations. As well, we feature a new climate solutions dual-degree program and a new fund-based class to prepare students to lead the transition to a more sustainable future.

Leading the Next Wave of Behavioral Economics

By Laura Counts & Mickey Butts

Ever since future Nobel laureates George Akerlof and Daniel Kahneman created a 1987 UC Berkeley course that broke the barrier between psychology and economics, the university has led the way in bringing these disciplines together into the field of behavioral economics.

Ever since future Nobel laureates George Akerlof and Daniel Kahneman created a 1987 UC Berkeley course that broke the barrier between psychology and economics, the university has led the way in bringing these disciplines together into the field of behavioral economics.

In the ensuing years, psychology-based behavioral economics has explored the predictable foibles in our thinking, such as decision-making biases, fears of losing out, lack of self-control, and overconfidence. A classic example is Kahneman’s pioneering work with Amos Tversky on loss aversion, which showed that people are willing to take greater risks to avoid a loss than to secure a gain.

Now Haas is poised to lead the next wave, pushing the field beyond psychology and gleaning insights from disciplines as diverse as neuroscience, biology, and medicine with the launch last fall of the Robert G. and Sue Douthit O’Donnell Center for Behavioral Economics.

“Humans are living, breathing organisms affected by their unique life paths,” says Professor Ulrike Malmendier, the O’Donnell Center’s founding faculty director. “We have minds and bodies, and an economic science that describes human behavior needs to account for both.”

Thanks to a philanthropic investment of almost $17 million by Bob O’Donnell, BS 65, MBA 66, and his wife, Sue O’Donnell, the center will advance the next generation of research, extend learning opportunities to students, and position Haas as the preeminent hub for the field. Malmendier aims to bring in leading researchers from a wide range of disciplines for collaboration, conferences, and bootcamps—beyond what has been considered part of the field. The center will also provide fellowships to PhD students and postdoctoral scholars and will host the prestigious Behavioral Economics Annual Meeting (BEAM), co-founded by Malmendier, every three years.

Students will benefit from a curriculum enriched by the foremost thinkers in the field. In early April, for example, the O’Donnell Center co-sponsored a fireside chat with economist and Nobel Laureate Richard Thaler and New York Times writer David Leonhardt. Malmendier has also initiated a weekly reading group with faculty, PhD students, and post-docs to discuss the latest behavioral economics research. Such discussions will deepen the knowledge faculty bring to the classroom. And because of the interdisciplinary nature of the O’Donnell Center, the teaching of behavioral economics and finance will expand to students campuswide.

Breaking new ground

Malmendier’s goal is to open a new frontier in research that will help business leaders and policy makers. “We went from neoclassical economics that considered humans to be perfectly rational to behavioral economics that brought in social psychology,” explains Malmendier, the Cora Jane Flood Professor of Finance.

For example, after Nobelist Thaler and Cass Sunstein developed the concept of the “nudge”—interventions that spur people to act in their own self-interest, such as enrolling them in a retirement savings plan by default—hundreds of “nudge units” were established in governmental and private-sector organizations around the world. Just last spring, a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine called for increased collaboration between behavioral economists and policymakers in part to encourage people to make better decisions.

“Now we want to move the needle further, bringing together the best minds for rigorous research on human behavior from the sciences more broadly, including neuroscience, cognitive science, biology, medicine, epidemiology, and genetics,” Malmendier says.

Pioneering collaborations

For her part, Malmendier will expand her groundbreaking work on “experience effects,” which earned her a Fischer Black Prize in 2013 for the top economist under the age of 40—the only woman to ever win the prize—and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2017. She has studied how stressful experiences with recessions, layoffs, inflation, housing bubbles, and political repression make consumer and investor behavior more cautious and risk averse for years afterward. She’s also explored how stress can affect our health, careers, education, and other aspects of life in dramatic ways.

Now, she aims to further that work by collaborating with neuroscientists, neuropsychiatrists, biologists, medical researchers, and epidemiologists who have studied stress and trauma—insights that could more precisely demonstrate how past experiences shape our actions, such as completing an education, choosing an occupation, and deciding to have a family, today and across generations.

“As we walk through life, our outlook on the world changes, especially if we suffer trauma,” she says. “Neuroscience says our brain gets rewired. There may be a long-term impact of stress on our longevity, on our aging, and on our health.”

In addition to Malmendier, the center will include a host of affiliated researchers from Haas and Berkeley Economics and elsewhere across the university. They include center co-founder Stefano DellaVigna, professor of economics and business; Haas professors Ricardo Perez-Truglia, Ned Augenblick, Don Moore, and Gautam Rao, PhD 14 (who recently joined Haas from Harvard University); as well as Dmitry Taubinsky of Berkeley Economics, and others.

“We want to move the needle further, bringing together the best minds for rigorous research on human behavior from the sciences more broadly, including neuroscience, cognitive science, biology, medicine, epidemiology, and genetics.”

—Prof. Ulrike Malmendier

Shaping transformative leaders

Founding donor Bob O’Donnell says he was inspired by the interdisciplinary promise of behavioral economics at Haas. “UC Berkeley is dedicated to integrating business education with other disciplines on campus, which is essential in this area,” he says. “It should have a center devoted to continuing this work.”

O’Donnell, a retired portfolio manager for a large mutual fund group, often applied insights from behavioral economics during his career. “When combined with existing financial theory, I believe that its insights enhanced results for my clients,” he says.

Yet, during the 17 years O’Donnell taught an investment class in the Berkeley Haas MBA program, he says he sometimes encountered skepticism when introducing ideas from the field. “Indeed, one student asked, ‘Isn’t all this kind of woo-woo?’” he says. “Several years later, that student told me how perspectives from behavioral economics had helped her career in finance.”

O’Donnell envisions his endowed gift as one that will not only define the future of behavioral economics but shape truly transformative leaders. Founding the center, he says, is a start but more investment is needed to enhance curricular offerings and expand the groundbreaking research that will be the hallmark of the O’Donnell Center.

Malmendier is passionate about the potential of behavioral economics to help leaders create better solutions to the most complex and urgent problems of our time, like battling inflation. “If leaders keep in mind people’s emotions, their personal histories, and their psychologies,” Malmendier says, “they can engineer ways to make things more predictable and give people more control over events to help them live better lives. That is our ultimate goal.”

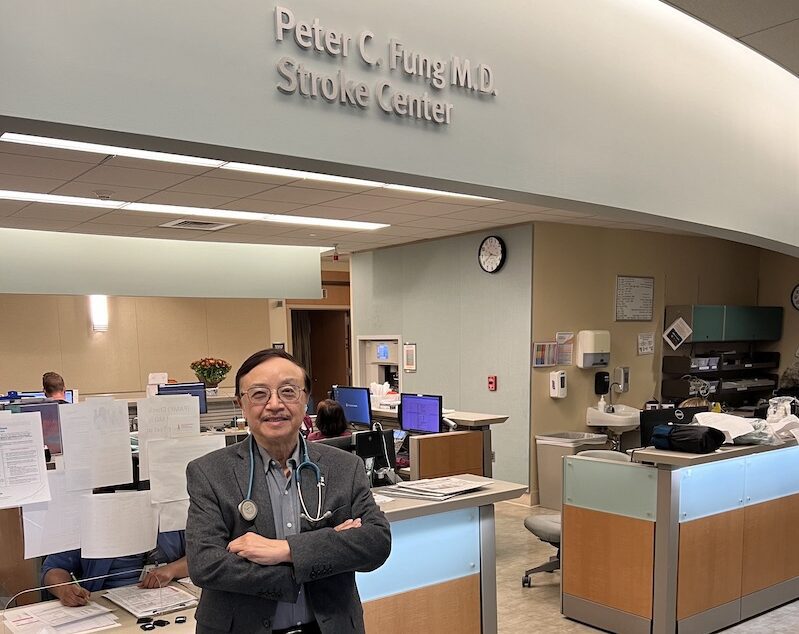

Harnessing AI to Transform Healthcare Outcomes

By Amy Marcott and Laura Counts

The U.S. spends almost 20% of its gross domestic product on healthcare—more than any other high-income country. Yet we see a low return on that investment: Americans have poor outcomes across numerous dimensions, including life expectancy.

The U.S. spends almost 20% of its gross domestic product on healthcare—more than any other high-income country. Yet we see a low return on that investment: Americans have poor outcomes across numerous dimensions, including life expectancy.

A big factor in these poor outcomes is a healthcare system that resists easy remedies, says Haas Professor Jonathan Kolstad. Promising innovations and technologies are often dead on arrival due to lack of understanding of the incentives at play.

“There’s a big gap between the kinds of AI and machine learning tools that are being built for healthcare and the realities of the healthcare delivery system, including the complex incentives, how the system functions, who would buy the product, and who would use it,” he says. “Conversely, the healthcare system is behind in terms of the technology, the systems, and the adoption of new AI tools. Right now, there’s a unique opportunity to play massive catch-up.”

The new Center for Healthcare Marketplace Innovation (CHMI), a joint endeavor between Haas and Berkeley’s new College of Computing, Data Science, and Society, aims to bridge that gap with solutions that join AI and data science with behavioral economics and an understanding of the realities of the healthcare system and the vagaries of human behavior.

Launched this spring with a gift from an anonymous donor, the CHMI combines technology development and academic research, giving researchers and partners access to a massive database of healthcare data. In fact, CHMI is believed to be the first applied research center of its kind to merge data, behavioral economics, and artificial intelligence with a focus on technology incubation.

Applied behavioral economics

Previous approaches to healthcare innovation are often too simplistic, Kolstad says, while other technologies have simply aimed to replace doctors. “These are some of the smartest and most highly trained humans making lots of different decisions under complex situations—which machines simply cannot do,” he says. “It’s the interaction of technology and human decision-making where AI is going to meet the market in healthcare.”

Take, for example, helping a radiologist better identify cancer. To do so successfully, Kolstad says, requires understanding the realities of how radiologists work, what they try to do, when cancer is spotted, who’s being screened, what data are available with the right pictures, and even how they’re paid. “All of those layers are critical,” he says.

Kolstad is building a database that he hopes will be one of the largest multimodal healthcare data platforms in the world. This rich data will include health insurance claims as well as medical records, images, electrocardiogram waveforms, and other granular information all linked to longitudinal health outcomes. The platform will be available for both research and R&D. “We want to structure it so that you can use the data to learn and create new insights but also create new solutions that really meet patients where they are,” Kolstad says.

“It’s the interaction of technology and human decision-making where AI is going to meet the market in healthcare.”

—Prof. Jonathan Kolstad

In addition to this novel data platform, CHMI will also offer academic and industry partnerships to facilitate the development of new AI and technology solutions grounded in real-world problems; the incubation of new companies; and academic research on AI, behavioral economics, and economic incentives. The interdisciplinary center will work with researchers throughout UC Berkeley and at UCSF.

The importance of incentives

What’s key to success, Kolstad says, is working within the constraints of a complex, market-driven healthcare system bolstered by governmental incentives. “At the end of the day, you have to understand the incentives in order to create solutions that are going to get to scale and change things,” he says. “We’re facilitating what we think will make that system more effective, more productive, and more efficient, which will lead to better health at a lower cost.” Kolstad himself has done this with the launch of a new company, Healthpilot, to help improve Medicare (see sidebar, “Haas Research Fuels Company Benefiting Medicare Patients”).

“My strong hope for CHMI is that there will be novel technologies that will be positioned to create new startups, nonprofits, or open-source solutions,” says Kolstad, the Henry J. Kaiser Chair. He’s forming relationships with venture funds, big insurers, and government agencies keen to see CHMI innovations—executives who can collapse the time it typically takes to run a pilot and scale. “We’re here to actually change things,” Kolstad says.

Doubling Down on Sustainability

By Kim Girard and Laura Counts

Since Dean Ann Harrison assumed leadership of Haas five years ago, she has made sustainability a strategic priority for the school, working to ensure that students are trained to view leadership challenges with a sustainability lens. Undergrads can now minor in sustainability, MBA core courses are being revamped to incorporate thinking about climate change and other sustainability challenges, and Haas launched the Michaels Graduate Certificate in Sustainable Business, to name just a few offerings.

Now, MBA students wishing to deepen their training in the field have two new opportunities available to them: a dual-degree option and a pioneering Climate Solutions Fund class.

Master’s degree in business and climate solutions

Haas and Berkeley’s Rausser College of Natural Resources recently launched the concurrent MBA/Master of Climate Solutions to prepare the next generation of sustainability and climate leaders. The new program, enrolling for fall 2024, will allow students to earn a master’s degree in both business and climate solutions in five semesters, one more than is typically required for the full-time MBA.

Dean Harrison says the degree will teach critical skills and knowledge in climate data science, carbon accounting, and lifecycle analysis as well as technological and nature-based solutions. “Future business leaders will require a depth of training in both business and climate change to work across disciplines and execute competitive strategies,” she says. “This new program will provide a breadth of skill sets, equipping our grads to lead in building a sustainable, low-carbon future.”

Students in the MBA/MCS cohort will spend the first year at Haas completing MBA core coursework—which includes courses in leadership, marketing, management, finance, data analysis, ethics, and macroeconomics, along with sustainability courses—before moving to classes at Rausser. The MCS core curriculum includes climate and environmental sciences; climate economics and policies; technological, business, and nature-based solutions; training in analytical and quantitative skills; and applied exercises and engagements that emphasize adaptive thinking and problem-solving. MCS courses will translate the fundamental science and groundbreaking discoveries of UC Berkeley experts, enabling professionals to learn how to evaluate technologies, develop just climate strategies, and remove barriers to implementing practical climate solutions.

“Future business leaders will require a depth of training in both business and climate change to work across disciplines and execute competitive strategies.”

—Haas Dean Ann Harrison

Michele de Nevers, executive director of Haas’ Office of Sustainability and Climate Change, says the dual-degree’s focus on early-career professionals promises quick dividends. “These professional students are clearly positioned to make an immediate impact and will serve a critical role as translators of academic insights and enacting these insights in the world,” she says.

All MBA/MCS students will participate in a semester-long capstone program that gives them the opportunity to partner with organizations operating across the business, government, and nonprofit sectors. A unique leadership course on organizational, political, and societal change for climate solutions will prepare students to be change agents anywhere they work. Students will also complete two summer internships, which will allow for deep immersion in different disciplines and more time to build relationships.

James Sallee, a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics and faculty director of the MCS program, says that while new research on climate solutions is still critical, many of the things needed to address the climate challenge are already known. “What we really need are people spread throughout society and the economy who are in a position to take action on climate and who are equipped with the tools to make the right choices. Educating those students is the vision of the MCS program,” he says.

New Climate Solutions Fund

Financing the climate transition requires a diverse and technical tool kit: An estimated $4 trillion to $5 trillion per year will be needed to reshape global energy, transportation, food, and waste infrastructure and to help companies reinvent supply chains and integrate new technologies, says Professor Adair Morse.

To equip future leaders with the financial know-how to accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy, Haas is launching the student-led Climate Solutions Fund in fall 2024—the first such course at a major business school.

MBA students in the course will serve as investment managers for the $2.37 million fund, learning how to structure financing in complex private markets by investing in real-world deals focused on solutions to climate change.

It was conceived of by Morse, co-founder of the Sustainable and Impact Finance Center (SAIF). “As the world moves toward a goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, we need financial leaders with the skills to navigate the economic revolution we are facing,” she says. “This economic revolution will be staggeringly disruptive yet will also be a source of more business opportunities across all parts of the country than we’ve seen in 250 years.”

The Climate Solutions Fund curriculum will teach students new designs and uses of finance not traditionally taught in mainstream finance courses, including public-private partnerships with federal and state programs, identifying the underlying technologies to fuel the low-carbon transition, and envisioning new financial products. Morse saw the need for this financial expertise while serving as deputy assistant secretary of capital access in the U.S. Department of the Treasury from 2021 to 2023.

“As the world moves toward a goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, we need financial leaders with the skills to navigate the economic revolution we are facing.”

—Prof. Adair Morse

“This level of reinvestment [in the climate transition] will require every finance tool available, including designing financial structures to mobilize government programs and work with community and industry partners,” she says. “Our goal is to expand how we teach students to provide the leadership and expertise that corporations, financial entities, startups, governments, and philanthropies will need to navigate this transition.”

Students in the course will assess investment opportunities in U.S.–based for-profit companies, working with outside investment partners to structure deals. Following a pitch competition, student managers will select one finalist to co-invest $100,000 to $300,000 annually. The fund is intended to generate positive returns over time so that future students can build off the capital.

The Climate Solutions Fund was made possible by a lead gift from Allan Holt, MBA 76, along with generous founding donations from Larry Johnson, BS 72; Charlie Michaels, BS 78, and his wife, Doris; Scott Pinkus; and Professor Laura D. Tyson, former Haas dean and co-founder of SAIF.

During her 12-year career at One Medical, Amy Finney held many leadership positions. But her most consequential role came in February 2020, when she led One Medical’s emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

During her 12-year career at One Medical, Amy Finney held many leadership positions. But her most consequential role came in February 2020, when she led One Medical’s emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Berkeley Haas welcomed an accomplished group of nearly 700 new full-time

Berkeley Haas welcomed an accomplished group of nearly 700 new full-time