In navigating the opportunities and challenges of innovating within large corporations, alumni build on decades of trailblazing Haas thought leadership.

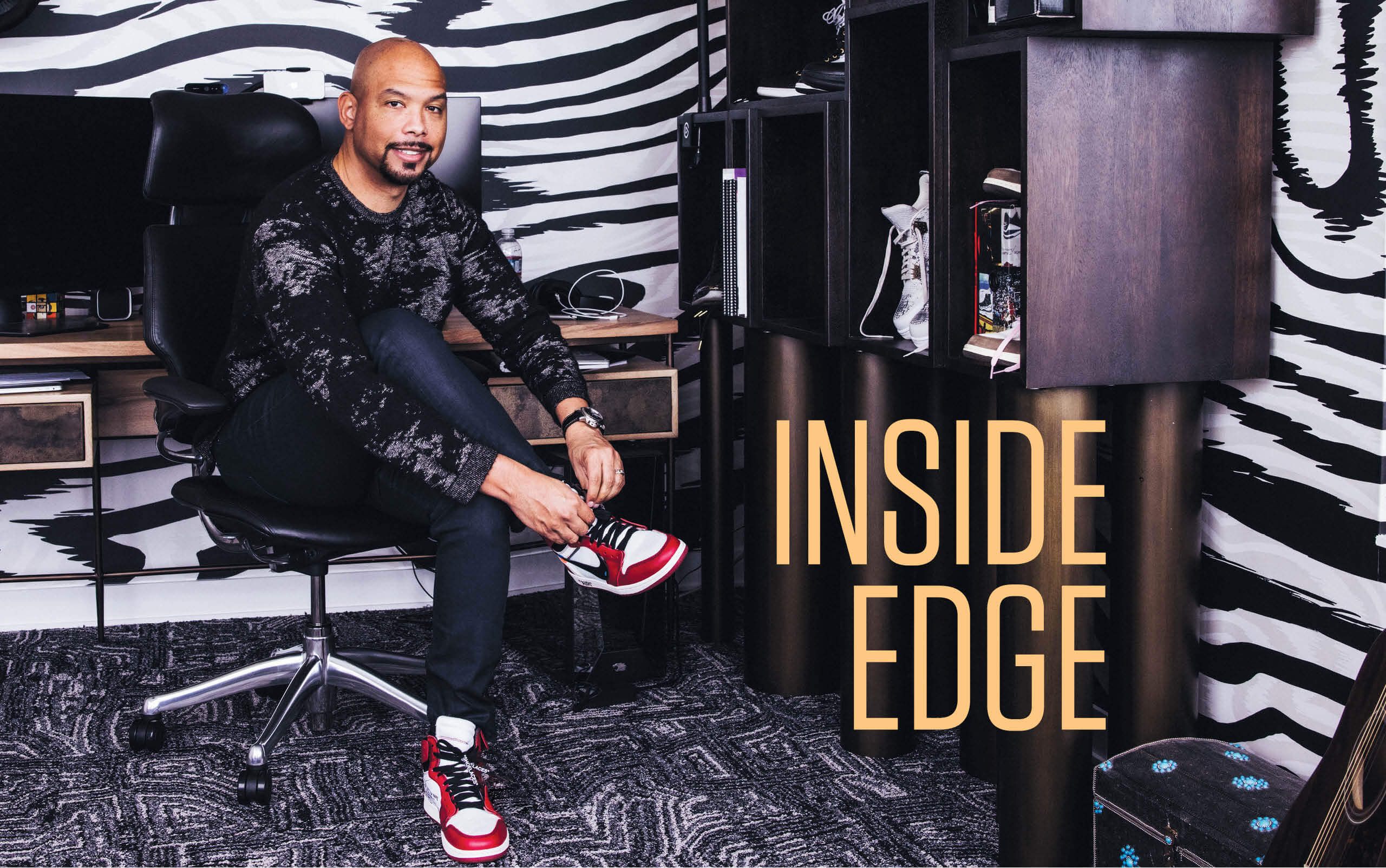

Innovation is often considered synonymous with startups, but when it comes to developing groundbreaking products and services, company size doesn’t matter. Intrapreneurs, or those innovating within a large corporation, are just as inventive. Case in point: Nick Caldwell, MBA 15. The product development and engineering leader has ascended the ranks of the tech industry and is now the general manager of core technologies at Twitter. But he didn’t cut his teeth at a startup.

Instead, he honed his entrepreneurial skills from within the Microsoft Corporation, where he worked for 15 years. During his time there, he founded many product efforts, including the company’s business intelligence software, Power BI.

Caldwell says that when it comes to innovation, large firms have some distinct advantages over startups. “Big companies have magnitudes more resources and an existing business ecosystem of products they can leverage,” says Caldwell. “You can take more shots on goal because you’re building on the back of existing businesses.”

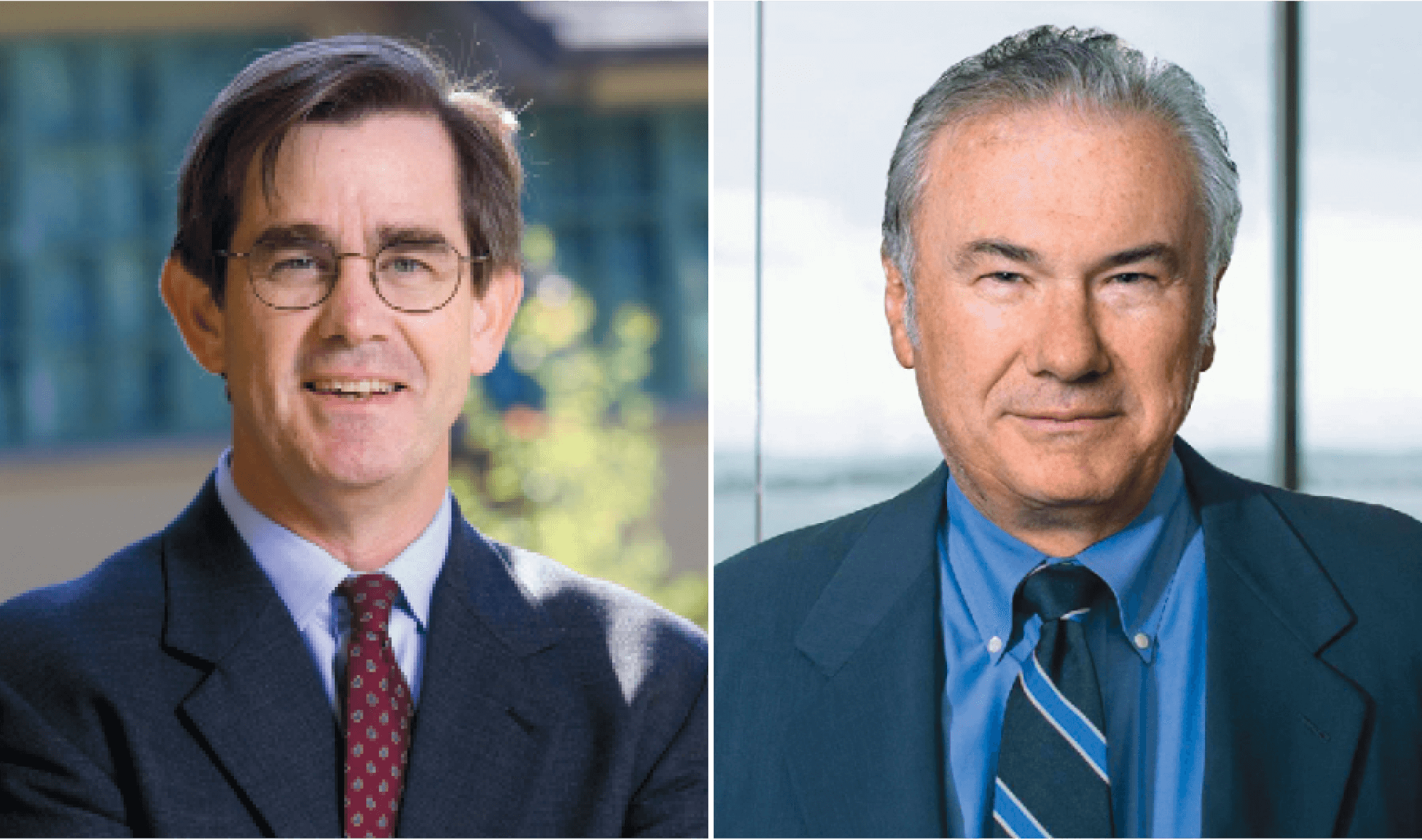

The idea of corporate innovation is ubiquitous these days, but Haas is central to its origin story. Two key figures are Professor David Teece, known for his theory of dynamic capabilities, and Adjunct Professor Henry Chesbrough, PhD 97, known for his paradigm of open innovation.

Chesbrough’s inspiration came from his work as a product manager at hard drive company Quantum. Most of the company’s business was in selling drives to other companies, but in 1984, Chesbrough joined a new venture to sell them directly to end users. The new company, dubbed Plus Development, was 80% owned by Quantum and 20% owned by the employees themselves.

“We were only allowed to hire five engineers from Quantum—everything else we had to do ourselves,” he recalls. Having the backing from the parent company gave him and his fellow intrapreneurs the resources they needed to get the business off the ground. The internal startup eventually blew open an entirely new market. “We ended up with revenues over $100 million and gross margins of over 40%,” Chesbrough says.

He went on to earn a PhD in business and public policy at Haas, where he focused on how companies could successfully innovate new products. One of his mentors was Teece, who was strategizing how companies could retain their competitive edge and resist losing out to new disruptors.

The groundbreaking theories of dynamic capabilities and open innovation led Haas to become one of the nation’s top business schools in teaching principles of innovation, catalyzing the field of study. Gary Pisano, PhD 88, a professor at Harvard Business School, experienced this firsthand as one of Teece’s doctoral students. “Today we take innovation for granted but Haas really was a pioneer,” says Pisano, who remembers not just the academic rigor but also the guest speakers from business and government who visited campus. “Haas started to become an intellectual hub on the serious work of innovation management and strategy—an influence not just in the form of papers but also PhD students who went off to teach at various business schools nationwide.”

Haas as trailblazer

Yet it wasn’t a given that learning to lead innovation would become an essential part of business education. In the ’80s and ’90s, Pisano says, the common belief was that corporate structures were poorly suited for innovation. “But the Haas way of thinking of it was that firms matter, that organizational structures for certain kinds of innovation can be incredibly helpful,” he says. It’s that perspective of innovation as essential, not just for scrappy startups but for established companies as well, that has minted graduates who have pushed innovative products and ideas at places like Google, Facebook, Amazon, and many others.

Alex Levich, MBA 09, a product management lead at Google who presents publicly on best practices for intrapreneurialism, is one of those graduates.

At Google, she worked on the creation of the Chromebook to extend cloud computing to individual users as well as the USB-C connector as a universal power connector that has become the industry standard—an example of open innovation at work. “We wanted to create a future where no one ever worried about missing a particular cable to charge a device,” she says, “so we set out to create a new standard by joining forces with the [nonprofit] USB Implementers Forum and users across the country.”

Dynamic capabilities

Teece contended it wasn’t enough for companies to innovate—they also had to profit from those ideas, arguing in an influential 1986 paper that access to manufacturing, marketing, distribution, and other complementary assets on favorable terms was just as important to success as R&D. Over the next decade, he developed the framework of dynamic capabilities, which insists that companies need to constantly sense, seize, and transform to take advantage of both internal and external opportunities for growth. The pursuit of efficiencies and even “best practices” sometimes got in the way.

“Dynamic capabilities really put the management team front and center in the innovation process,” Teece says. “It’s not just about having the best engineers and scientists; you also need good entrepreneurial managers to succeed.” Without them, he says, companies too often become bogged down in administrative processes or, worse, focused on efficiency to build value. “You can’t build a company to greatness on cost cutting—that’s a short-term game,” he says. Companies must also overcome what Teece calls the “persistence bias” of continuing to do things the same way. Apple under Steve Jobs is a classic success story. “He really saw an opportunity for a phone of the future that would be first and foremost a computer with a phone and internet connectivity built in rather than a phone with a few smart features, which is what Nokia was doing,” Teece says. More recently, companies such as Amazon and Netflix have shown a constant ability to pivot and launch new products and services, even as they grow very large.

Pisano (shown right), a co-author of the 1997 article on dynamic capabilities, says that Teece’s brilliance lies in his ability to synthesize ideas from across fields. “Organizational economics was historically separate from work on strategy, which was historically separate from work on innovation,” Pisano says. “David brought together three very different fields and that created some new paradigms and ways to think about a whole range of problems.”

Pisano (shown right), a co-author of the 1997 article on dynamic capabilities, says that Teece’s brilliance lies in his ability to synthesize ideas from across fields. “Organizational economics was historically separate from work on strategy, which was historically separate from work on innovation,” Pisano says. “David brought together three very different fields and that created some new paradigms and ways to think about a whole range of problems.”

Open innovation

Chesbrough’s concept of open innovation stems from field research with Xerox in Palo Alto in the 1990s. He examined 35 innovative projects within the company, finding that all but 10 of them failed. “The ones that succeeded were those that found a way to make them attractive to external partners and make money for themselves in the process,” he says. For example, when engineer Robert Metcalfe created a smart cabling system to connect printer components, he realized it could have much broader uses and negotiated a royalty-free contract for the technology for $1,000. He used his new Ethernet cable to connect IBM computers to HP printers, eventually spinning out the company 3Com, which eclipsed Xerox in value.

Now faculty director of the Garwood Center for Corporate Innovation, Chesbrough says that companies succeeding in innovation today often similarly look beyond their own business to find collaborations with outside partners—sometimes even with competitors. That’s what Amazon did in the mid-2000s when they realized that other firms might also have difficulties managing servers as they scaled. So they sold to other companies—including their competitor Barnes & Noble—the ability to host their websites on Amazon’s infrastructure. Out of these experiments the company created Amazon Web Services, an innovator in cloud technology. “Amazon has fostered a culture that allows people to try these experiments,” Chesbrough says. “They key is you’re learning from your interactions with customers and the market.”

“Companies with successful intrapreneurs break new ideas down into manageable building blocks and assign cross-functional teams that aren’t afraid to experiment and fail.”

—Alex Levich, MBA 09

Winning big

What does it take to achieve intrapreneurial success? In Caldwell’s experience, it’s essential to have backing at the highest level. “Teams responsible for innovation must be well-protected and have top-down support,” Caldwell says. “The worst thing is your new innovative bet is killed by internal antibodies that don’t want the disruption and are incentivized toward stability. Leaders often have to reinforce strategy and make sure it is broadly communicated.”

At the same time, he says, you must reassure stakeholders that incremental improvements are valuable and will pay off down the line.

Recently, Caldwell helped spearhead a reimagined Explore page for Twitter that relies on algorithms to recommend new posts based on users’ changing interests over time rather than people they follow. To move quickly, he secured support from other executive leaders and assembled a “virtual team” of engineers, product designers, and marketers rather than creating a new department. After a lightning-fast three months, Twitter rolled out the page to users in a select geographic area and is now monitoring time spent engaging with the app. “We carved out a safe space for experimentation, and now we can tie it back to specific metrics,” he says. “It’s important that you have key results or objectives you want a team to achieve by a particular milestone, and hopefully a team can make an honest assessment of whether they are achieving those targets.”

Culture of innovation

Google’s Levich stresses that companies with successful intrapreneurs create a culture of innovation that starts with hiring and recruiting people with the right mindset. “For the company to have that culture in its DNA, they must believe that this is what delivers the most value to the company,” she says. From there, the company must break new ideas down into manageable building blocks and assign cross-functional teams that aren’t afraid to experiment and fail. “If teams are filled with people who have not failed, that probably means they didn’t aim high enough,” she says.

Often, corporations develop their own specialized processes to organize innovation efforts. At Amazon, any employee can propose a new product or program by submitting a document called a PRFAQ, says Uday Tennety, MBA 13 (shown right), who spent over four years at the company leading product and go-to-market strategies. The document, he says, explains customer problems and how the proposed product or program solves them. Employees also detail the plan to complete it. This allows good ideas to come from anywhere within Amazon while also subjecting them to rigorous analysis before pressing go.

Often, corporations develop their own specialized processes to organize innovation efforts. At Amazon, any employee can propose a new product or program by submitting a document called a PRFAQ, says Uday Tennety, MBA 13 (shown right), who spent over four years at the company leading product and go-to-market strategies. The document, he says, explains customer problems and how the proposed product or program solves them. Employees also detail the plan to complete it. This allows good ideas to come from anywhere within Amazon while also subjecting them to rigorous analysis before pressing go.

“Companies that succeed in innovation today often…look beyond the four walls of their own business to find ways to collaborate with outside partners—sometimes even with competitors.”

—Adjunct Prof. Henry Chesbrough, PhD 97

“It enables you to think very deeply and gather valuable feedback to solidify the idea,” says Tennety. At Amazon, he used the company’s innovation process to lead new product AWS Panorama to market. AWS Panorma allows companies to combine cameras and computer algorithms to improve processes such as employee check-in, inventory or cargo management, and food services operations. He recently left Amazon for Nile, a new startup offering secure connectivity as a service.

While companies like Google and Amazon make innovation look easy, other companies have struggled to put together the right combination of leadership, culture, and processes to make innovation work. After years of innovating under CEO Bill Gates, Microsoft struggled from 2000 to 2014 during the tenure of his successor Steve Ballmer, who’s been criticized for focusing too much on the core software business at the expense of new offerings. That’s turned around under new CEO Satya Nadella, however, says Teece, as the company has made up for lost time in entering cloud computing through its Azure portal.

Juhi Saha, EMBA 15 (shown right), had a front-row seat to that transformation in positions including global director of strategic startups and director of financial services. Saha ran a program to provide high-profile, VC-backed startups with white-glove onboarding into Microsoft’s ecosystem, which enables them to sell through Microsoft’s sales channels. Rather than supporting companies just through their cloud migration, Microsoft shifted to supporting customers through their entire cloud journey to increase top- and bottom-line revenue for these companies.

Juhi Saha, EMBA 15 (shown right), had a front-row seat to that transformation in positions including global director of strategic startups and director of financial services. Saha ran a program to provide high-profile, VC-backed startups with white-glove onboarding into Microsoft’s ecosystem, which enables them to sell through Microsoft’s sales channels. Rather than supporting companies just through their cloud migration, Microsoft shifted to supporting customers through their entire cloud journey to increase top- and bottom-line revenue for these companies.

“Access to Microsoft’s marketplace where they can transact deals has been a game-changer for fast-growing companies, enabling them to take their business to the next level,” she says. “I’ve seen a company close a deal in six weeks that would typically take nine months and quintuple the deal size—simply because they worked with Microsoft sellers to transact through this marketplace.”

Saha says a change in culture made all the difference. Leaders began rewarding risk-taking employees who weren’t afraid to fail, overcoming a previous culture of fear. Departments such as marketing and business operations became more decentralized. “There was freedom to experiment,” says Saha, who recently left after five years to join marketing technology firm Clearbit as vice president of partnerships and alliances. “It was refreshing to work with some amazing sales leaders who were fearless about providing an innovative, customer-centric culture.”

Different strokes

Companies that struggle to innovate within their existing framework can take advantage of other models to help them create new products and services. As a venture build director at BCG Digital Ventures, the corporate innovation and digital-business-building arm of Boston Consulting Group, Julia Felts, EMBA 15, works with corporations to manage the whole innovation process, from ideation to incubation to execution of ideas. She is inspired by the design-thinking process she learned at Haas from Teaching Professor Sara Beckman. Companies often reach out, she says, “when they see there is a space for something in their industry, but they don’t think they can get there fast enough with their current teams.” Felts assists companies in creating separate fully or partially owned startups and supports the recruitment of executive leaders with startup experience who might be looking for the stability a large company can provide.

Sometimes, companies have assets available to generate new business. Recently, she helped UPS create Ware2Go, a digital marketplace connecting small and medium-sized companies with available warehouse space nationwide, which allows for faster delivery times and optimized transportation costs. Felts sees her job as the best of both worlds, being able to build something new with industry leaders without having to worry about raising venture cash. “I get to build a business that’s already funded with the best resources and the best people—it’s really impactful to build something at the forefront of innovation when there’s so much support.”

Julia Felts, EMBA 15, sees her job as the best of both worlds, being able to build something new with industry leaders without having to worry about raising venture cash.

Not all innovation is conducted with profit in mind. As edtech lead for corporate social responsibility at Verizon, Phil Puthumana, BCEMBA 07 (shown right), spearheads the company’s efforts to help bridge the digital divide and improve education through technology. His group works with nonprofits to bring tablets and other technology into high-need schools and to train teachers how to integrate technology, such as virtual or augmented reality, in classrooms.

Not all innovation is conducted with profit in mind. As edtech lead for corporate social responsibility at Verizon, Phil Puthumana, BCEMBA 07 (shown right), spearheads the company’s efforts to help bridge the digital divide and improve education through technology. His group works with nonprofits to bring tablets and other technology into high-need schools and to train teachers how to integrate technology, such as virtual or augmented reality, in classrooms.

When the pandemic hit in 2020, the team moved to create Verizon Innovative Learning HQ, a free next-gen education portal with resources that include innovative learning apps, tailored lesson plans, and professional development courses as a remote resource for educators nationwide. As schools have dealt with continuing uncertainty, those tools can be available in both remote and hybrid learning formats, Puthumana says. Since launching in August 2021, the program has already reached some 500,000 students with a goal of reaching 10 million in 10 years.

Puthumana’s group has succeeded, he says, by aligning its goals with the larger goals of the company. In addition to helping students, the initiative provides an opportunity to test and explore apps that can take advantage of newer 5G networks. At the same time, it creates a halo for the brand in its sincere attempts to go beyond just writing philanthropic checks to fulfilling the needs of students and teachers in new ways. “We work with great intentionality to be genuine and respectful of our audience,” Puthumana says. “At the same time, customers have a lot of choices, and we hope that they feel better about choosing us because of the positive impact we’re making in our communities.”

Entrepreneurial culture

When it comes to questioning the status quo—from both an academic and practical perspective—Haas plays a key role in the evolution of bringing novel ideas to market. And innovation continues to be a lens through which the school operates.

“A key concept at Berkeley Haas has to do with ‘new thinking,’” says Caldwell. “Both in the way we identify and solve problems and in the way people and organizations create networks of ideas we can tap into and contribute to.”

It is this emphasis on innovation as a worldview rather than a watchword that allows faculty, students, and alumni to constantly redefine how the world does business.