In honor of Black History Month, we’re running a series of profiles and Q&As with members of the African-American community at Haas. Follow the series throughout February here.

Curiosity fueled MBA student Jason Atwater’s bittersweet journey to uncover the history of his enslaved ancestors—and to walk the grounds of the Virginia plantation where they once lived.

“I always wanted to find out more about my family’s history,” said Atwater, a member of the 2019 class of the Berkeley MBA for Executives program, who grew up in Pennsylvania. “I thought it would be amazing if I could track down one of my enslaved ancestors, but I thought it would also be so unlikely because of the lack of information that was available.”

After five years of tracing his family tree on both sides, Atwater hit a research wall—specifically, the year 1870, when formerly enslaved people were listed by their names for the first time in the U.S. Census. But a lucky break came in 2017, when a distant cousin provided new information on Ancestry.com, where Atwater works as a digital marketing manager. Atwater had earlier registered his own DNA on Ancestry.

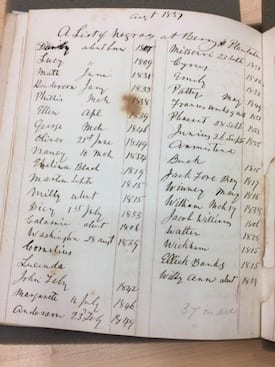

Along with a name—Matt Duncan—the cousin included a copy of a ledger, written by the owner of Berry Hill Plantation in Halifax County, Va. Atwater recognized Matt Duncan’s name: He was his two-times maternal grandfather. The ledger also included the names of Matt’s parents, Darby and Lucy Duncan. “It had their actual names, which was amazing,” Atwater said.

“This wave of emotion”

Darby Duncan, Atwater discovered, worked as first chef to the plantation owner, who at the time was the third wealthiest man in Virginia, owning 3,600 acres, and was a personal friend of Thomas Jefferson.

After an article about Atwater’s experience ran on the Ancestry.com blog, the company’s creative team suggested accompanying him to the plantation to document the experience. Atwater, along with his mother and sister, traveled with a film crew to Virginia in August 2017.

Watch a video of Atwater’s journey to Berry Hill Plantation with his mother and sister.

“It’s almost hard to describe how many emotions I was feeling simultaneously, driving up and getting out of the car and looking at the plantation and seeing how enormous it was—the mansion, the giant columns,” Atwater says in the video, as the family arrives at Berry Hill. “It was just overwhelming. I could just feel this wave of emotion, almost like being in the water when waves hit you, one wave at a time. Each wave was a different emotion. It was fear and sadness and happiness and anger, all just kept washing over me.”

The family toured the Greek Revival style mansion and a preserved stone building that served as slaves’ quarters—one of few that are still standing on the property. They also walked through Diamond Hill Cemetery, where more than 200 slaves are buried among unmarked stones. “All I could think about is that they’re here, they’re buried, but no one knows who they are,” Atwater said.

(The estate, which is now a conference and event center, was named a National Historic Landmark in 1969.)

A Darby cooking gene?

During a stop at Darby’s Tavern, a restaurant on the grounds that is named for Darby Duncan, Atwater touched a large metal pot that Darby used for cooking. Atwater learned that he had been sent to New Orleans to study creole cooking—and was considered a top chef of his time. In the midst of being an enslaved person, Darby had some autonomy, Atwater said.

“I tried to put myself in his position. What was his life like? Was he treated well?” Atwater says as he walks through the tavern in the video.

Cooking, he noted, is a passion shared by his entire family. “We inherited that from Darby Duncan,” he said. “The cooking gene.”

While in Virginia, Atwater also traveled to the Special Collections Library at University of Virginia in Charlottesville to view the Berry Hill Plantation ledger in person.

Atwater, who is co-vice president of diversity for the EMBA class, has shared his story with classmates, and encourages other African Americans to overcome any fear or shame they may feel in tracing their enslaved ancestors.

“It’s been a great experience, just so amazing to be there and connect with a piece of my family’s history,” Atwater said. “Complete strangers have written me about how the story touched them, and that’s led them to research their own families.”