Topic: Innovation & Technology

Decoding the Augmented Intelligence Matrix for Operational Excellence in the Digital Era

Japan’s top economic minister visits Berkeley Haas to spur innovation, collaboration

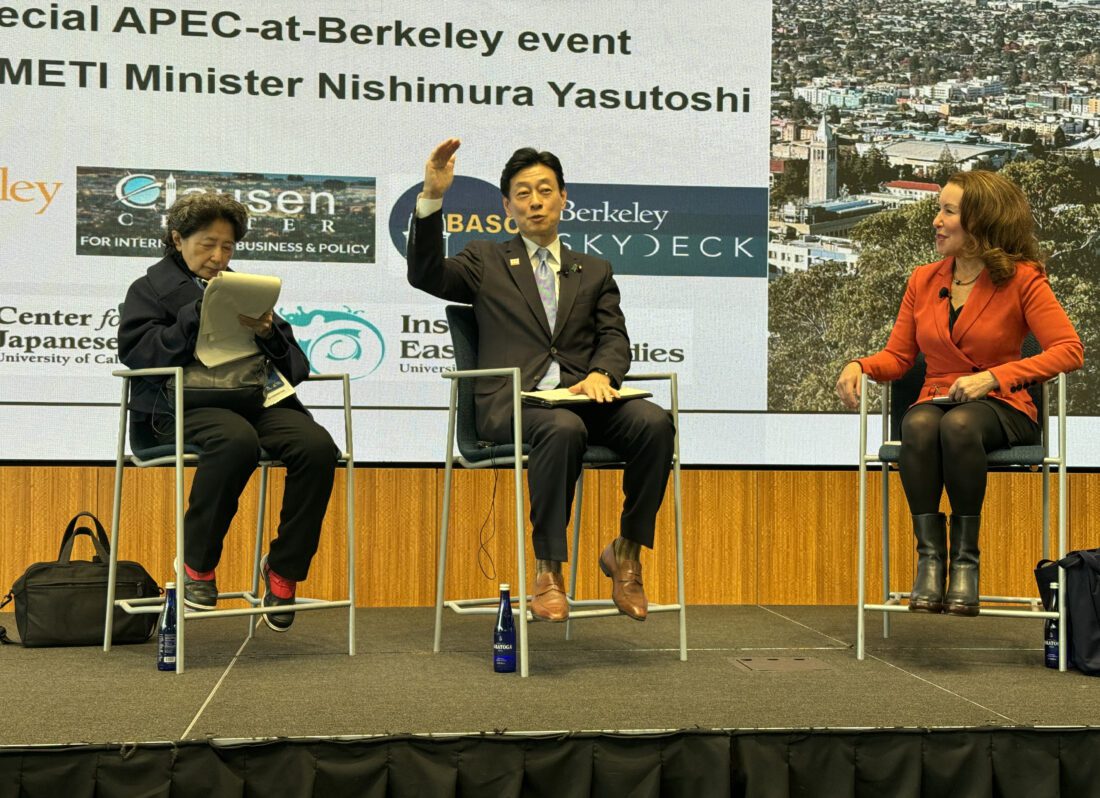

Nishimura Yasutoshi, Japan’s Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) visited UC Berkeley and the Haas School of Business this week to spread the message that Japan is making significant investments to transform its economy through entrepreneurship and innovation.

While Japan may be best known for its big companies like Toyota and Sony, “They began as startups first of all,” said Minister Nishimura, speaking through an interpreter in a conversation with Haas Acting Dean Jennifer Chatman. “Entrepreneurship is really in the DNA of the Japanese people.”

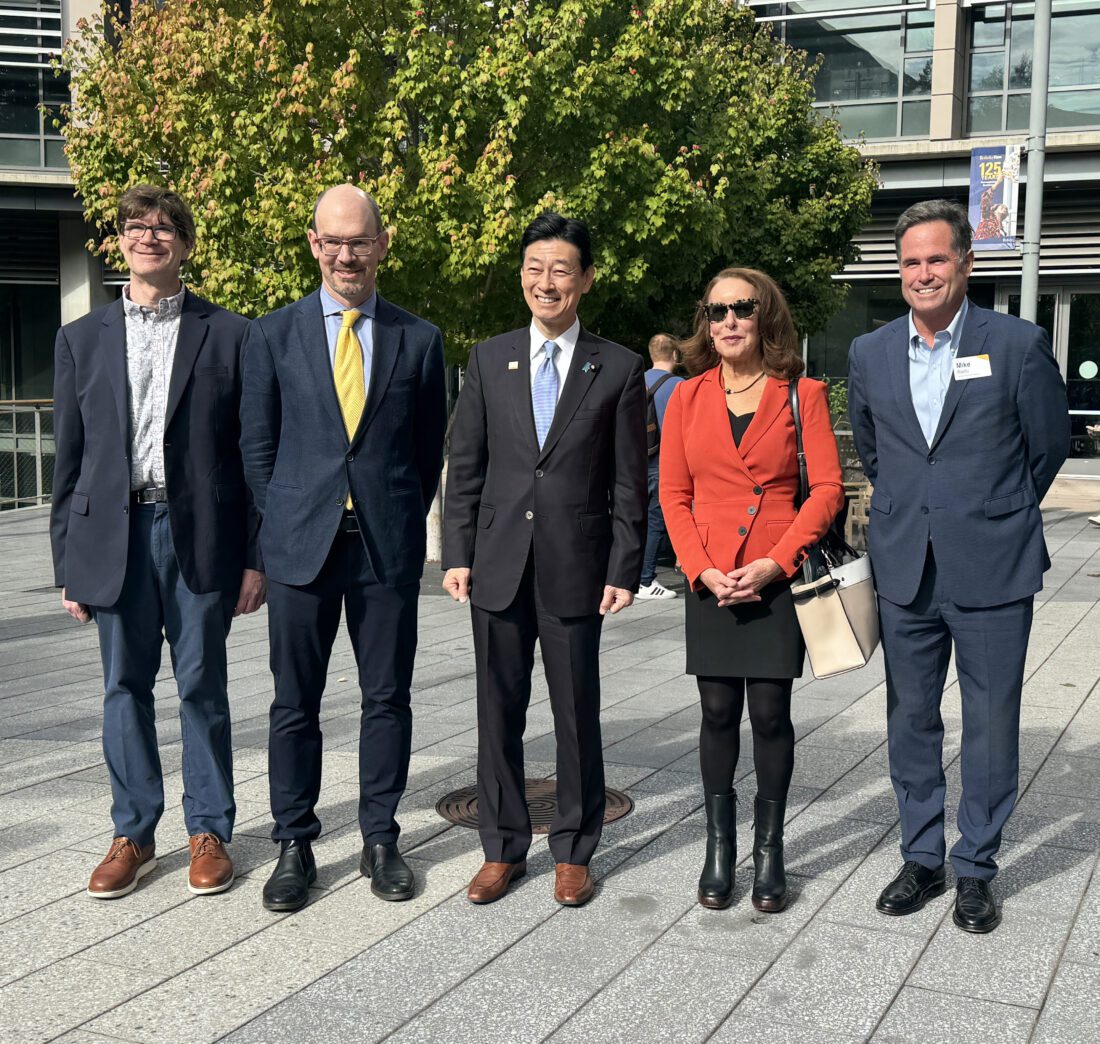

Invited to campus by the Clausen Center for International Business and Policy as part of events surrounding the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in San Francisco, Minister Nishimura’s visit also expanded the collaboration between UC-Berkeley and the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO). During the event, Caroline Winnett, Executive Director of the Berkeley SkyDeck accelerator, signed a memorandum of understanding with JETRO to further advance entrepreneurship, innovation, and scholarship.

Minister Nishimura also toured SkyDeck, which to date has hosted about 60 Japanese startups through its JETRO partnership.

Berkeley SkyDeck was thrilled to host Yasutoshi Nishimura, the Japanese Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry, for a visit to SkyDeck, following an MOU signing with @JETRO_InvestJP to launch our second international program. Learn more here: https://t.co/5SXLsxzXfy https://t.co/coKXsjQwyA

— Berkeley SkyDeck (@SkyDeck_Cal) November 17, 2023

In addition to the SkyDeck collaboration commemorated at Minister Nishimura’s talk, Berkeley Haas has a long tradition of partnering with Japanese companies and universities to promote innovation and entrepreneurship. In the past year, the Berkeley Haas Entrepreneurship Program has worked with Tohoku University to train top startups from the Sendai region in Lean Launch methodology. Haas has also hosted leading Japanese companies at the Berkeley Innovation Forum to explore building their innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystems.

To achieve its goal of a tenfold increase in the number of startups over the next five years, the Japanese government plans to send 1,000 entrepreneurs to the Bay Area over a five year span, and to invest in university partnerships, noted Haas Continuing Lecturer Jon Metzler, who helped organize the METI visit to Haas.

“The government of Japan is taking a number of measures to stimulate entrepreneurship, increase new venture formation, and nurture entrepreneurs with a more global mindset—including sending promising entrepreneurs to acceleration programs like Berkeley SkyDeck,” Metzler said.

‘Unicorns and decacorns’

After an introduction by Associate Professor Matilde Bombardini of the Clausen Center, Minister Nishimura delivered prepared remarks and sat for Q&A with Acting Dean Chatman. He said everyone who has visited Japan in the past few years is surprised by how much it has changed.

“In terms of macroeconomy, over the past 30 years because of deflation, it has been a challenging time for Japan. But now we are in an era when big changes are about to take place,” Nishimura said. Within the population of about 125 million, many entrepreneurs have been content to find success within the country. But Nishimura is encouraging young entrepreneurs to think big and “go global.”

“We are looking toward the emergence of many unicorns and decacorns,” he said.

Nishimura also talked about plans to build a next-generation semiconductor fabrication facility in Hokkaido, which will adopt a 2 nm fabrication process—a major technological leap compared to current fabs in Japan.

In addition to the Haas’ Clausen Center for International Business and Policy, the event was hosted in partnership with the Berkeley APEC Study Center, the Institute for East Asian Studies, the Center for Japanese Studies, and Berkeley SkyDeck, with support from the Haas Asia Business Club. The Japan Society of Northern California also helped promote the event.

NASA and UC Berkeley host discussion on the future of AI at work

Humans of Haas: Hari Parthasarathy

Critical Issues About A.I. Accountability Answered

Digitizing books can spur demand for physical copies

Impact of artificial intelligence on businesses

Scarcity as Strategy: Innovative Business Models for a Resilient Future

The Top 50 SaaS CEOs of 2023

Sins of the machine: Fighting AI bias

In a new working paper, Haas post-doc scholar Merrick Osborne examines how bias occurs in AI, and what can be done about it.

While artificial intelligence can be a powerful tool to help people work more productively and cheaply, it comes with a dark side: Trained on vast repositories of data on the internet, it tends to reflect the racist, sexist, and homophobic biases embedded in its source material. To protect against those biases, creators of AI models must be highly vigilant, says Merrick Osborne, a postdoctoral scholar in racial equity at Haas School of Business.

Osborne investigates the origins of the phenomenon—and how to combat it—in a new paper, “The Sins of the Parents Are to Be Laid Upon the Children: Biased Humans, Biased Data, Biased Models,” published in the journal Perspectives in Psychological Science.

“People have flaws and very natural biases that impact how these models are created,” says Osborne, who wrote the paper along with computer scientists Ali Omrani and Morteza Dehghani of the University of Southern California. “We need to think about how their behaviors and psychologies impact the way these really useful tools are constructed.”

Osborne joined Haas earlier this year as the first scholar in a post-doc program supporting academic work focused on racial inequities in business. Before coming to Haas, he earned a PhD in business administration at University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business last year. In their new paper, he and his co-authors apply lessons from social psychology to examine how bias occurs, and what can be done to combat it.

Representation bias

Bias starts with the data that programmers use to train AI systems, says Osborne. While oftentimes it reflects stereotypes of marginalized groups, it can just as often leave them out entirely, creating “representation bias” that privileges a white, male, heterosexual worldview by default. “One of the most pernicious biases for computer scientists in terms of the dataset is just how well-represented—or under-represented—different groups of people are,” Osborne says.

Adding to problems with the data, AI engineers often use annotators—humans who go through data and label them for a desired set of categories. “That’s not a dispassionate process,” Osborne says. “Maybe even without knowing, they are applying subjective values to the process.” Without explicitly recognizing the need for fairer representation, for example, they may inadvertently leave out certain groups, leading to skewed outputs in the AI model. “It’s really important for organizations to invest in a way to help annotators identify the bias that they and their colleagues are putting in.”

Privileged programmers

Programmers themselves are not immune to their own implicit bias, he continues. By virtue of their position, computer engineers constructing AI models are more likely to be inherently privileged. The high status they are granted within their organizations can increase their sense of psychological power. “That higher sense of societal and psychological power can reduce their inhibitions and mean they’re less likely to stop and really concentrate on what could be going wrong.”

Osborne believes we’re at a critical fork in the road: We can continue to use these models without examining and addressing their flaws and rely on computer scientists to try to mitigate them on their own. Or we can turn to those with expertise in biases to work collaboratively with programmers on fighting racism, sexism, and all other biases in AI models.

First off, says Osborne, it’s important for programmers and those managing them to go through training that can make them aware of their biases and can take measures to account for gaps or stereotypes in the data when designing models. “Programmers may not know how to look for it, or to look for it at all,” Osborne says. “There’s a lot that could be done just from simply having discussions within a company or team on how our model could end up hurting people—or helping people.”

AI Fairness

Moreover, computer scientists have recently taken measures to combat bias within machine learning systems, implementing a new field of research known as AI fairness. As Osborne and his colleague describe in their paper, fairness uses complex mathematical formulas to train machine learning systems on certain variables including gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and disability, to make sure that the algorithm behind the model is treating different groups equally. Other processes are aimed at ensuring individuals are being treated fairly within groups, and that all groups are being fairly represented.

Organizations can help improve their models by making sure that programmers are aware of this latest research and sponsoring them to take courses to introduce them to these algorithmic models—tools such as IBM’s AI Fairness 360 Toolkit, Google’s What-If Tool, Microsoft’s Fairlearn.py, or Aequitas. Because each model is different, organizations should work with organizational experts in implementing algorithmic fairness to understand how bias can manifest for their specific programs. “We aren’t born knowing how to create a fair machine-learning model,” Osborne says. “It’s knowledge that we must acquire.”

More broadly, he says, companies can encourage a culture of awareness around bias in AI, such that individual employees who notice biased outcomes can feel supported in reporting them to their supervisors. Managers, in turn, can go back to programmers to give them feedback to tweak their models or design different queries that can root out biased outcomes.

“Models aren’t perfect, and until the programming catches up and creates better ones, this is something we are all going to be dealing with as AI becomes more prevalent,” Osborne says. “Organizational leaders play a really important role in improving the fairness of model’s output.”

AI gold rush prompts some college students to drop out

California Forever CEO discusses start-up city in Solano County

Berkeley Space Center at NASA Ames to become innovation hub for new aviation, space technology

Build and orchestrate a hive brain across generations: Interview with UC Berkeley’s Olaf Groth

New book explores how companies can navigate a volatile future

Olaf Groth doesn’t like to make predictions, but he’s nonetheless become adept at helping executives see around corners and navigate the chaos of recent years.

A member of the Berkeley Haas professional faculty, a senior adviser at the school’s Institute for Business Innovation, and the faculty director for the Future of Tech program at Berkeley Executive Education, Groth is also chairman and CEO of thinktank Cambrian Futures.

In a new book, The Great Remobilization: Strategies and Designs for a Smarter World (MIT Press), Groth and coauthors Mark Esposito and Terence Tse (and editor Dan Zehr) focus on what they call the Five Cs—COVID; the cognitive economy, crypto and web 3; cybersecurity; climate change; and China. They show leaders how to power human and economic growth by replacing fragile global systems with smarter, more resilient ones.

In a new book, The Great Remobilization: Strategies and Designs for a Smarter World (MIT Press), Groth and coauthors Mark Esposito and Terence Tse (and editor Dan Zehr) focus on what they call the Five Cs—COVID; the cognitive economy, crypto and web 3; cybersecurity; climate change; and China. They show leaders how to power human and economic growth by replacing fragile global systems with smarter, more resilient ones.

In one chapter, the authors imagine a harrowing scenario they call “the Great Global Meltdown of 2028,” the economy collapses after a hack of a critical global payments system in the midst of recurring climate and COVID crises; nearly 1 billion people suffer mental health issues from the strain.

But with the help of the ideas in the book and a bit of practice, leaders can learn to “flip the chaos forward into opportunity,” the authors argue. The book, shortlisted for the Thinkers50 Strategy Award, launches on Oct. 17.

We talked with Groth about how executives can learn to turn turmoil into opportunity.

Your book talks about the need for humanity to make the leap from the “raging 2020s” to a “great remobilization” in the late 2020s and beyond. What will need to happen?

We’re looking at utter volatility over the next 10 years. We can’t afford to sit on the couch and just watch. We have an opportunity now to redesign how business leaders generate growth—both for their shareholders as well as for a broader set of stakeholders—that takes into account how the global economy has changed and continues to change. The book is all about: Where do we go from here? Are we going to accept that we’re going to have a fragmented world where people don’t trust each other, where trade and investment are inhibited, and where growth is limited?

“We can’t afford to sit on the couch and just watch. We have an opportunity now to redesign how business leaders generate growth—both for their shareholders as well as for a broader set of stakeholders—that takes into account how the global economy has changed and continues to change.”

What will the next era of globalization look like amid an era of rising economic nationalism, fragile supply chains, and recurring pandemics and natural disasters?

The globalization everyone keeps talking about is how many bananas get shipped from Argentina to China with the greatest degree of efficiency. And of course that’s important for jobs today. But what we really have to ask is, who controls the flow of any given thing from one place to another? At the end of the day, the people who have the power in what we call the “cognitive economy” can influence these flows. There are traditional flows—of capital, of intellectual property, of people, of goods and services. But there are also new flows of behavioral data, genetic material, and crypto currency. And that’s not even including the ecological flows of energy, air, water, and pathogens.

You define the cognitive economy as a world of algorithms automating or augmenting human decisions and tasks and spinning out valuable insights that can be used to improve businesses, governments, and society. What’s at stake for managers and leaders in a cognitive economic future?

In the cognitive economy, cybernetics functions are getting injected into everything we do—essentially intelligent, digital, command-and-control functions that are at the moment centrally steered by the likes of Google, Amazon, Baidu, and Alibaba. We need to see the new principles bubbling up now from the cognitive economy. Leaders need to be able to perceive the new operating logic in their domain and in their industry.

Take supply chains: 46% of supply chain managers are saying that investments in AI and automating human decisions is their top priority. That means we’ll see new types of integration of human and machine predictions and decisions. Or take the mobility industry. Electrified, autonomous cars use AI to create applications inside the car, and cars are now starting to be tied to a new charging infrastructure around the smart home. You need to design cars like they’re an iPhone: you start with a chip and you build everything around that. Essentially, the automotive industry is being scrambled, as is the energy industry, the home appliances industry, etc. Who controls these complex systems? How do you see those new patterns if you’re an executive any given industry?

Your book describes a FLP-IT (forces, logic, phenomena, impact, and triage) model for strategic leadership. How should executives approach the triage step, which requires them to make tough decisions about what to keep, discard, or build from scratch?

I was at the World Economic Forum meeting in Tianjin and a senior executive in the petrochemicals industry told me that after 30 years of building megafactories in China, his company now needed to throw that out the window and create chains of “nanofactories” across 12 different markets to create resiliency. To solve that kind of challenge you need to understand what to invest in and what to divest of. Because strategy is just as much about what you do as it is about what you no longer do.

Most executives are bad at dropping things that they hold dear. They need to make conscious choices.

“Most executives are bad at dropping things that they hold dear. They need to make conscious choices.”

Once you understand the new operating logic in your industry or domain, you need to redraw its boundaries and diagnose changed power relations. To address those changes, you have to then free up resources from activities that are not aligned with the new arena to create new ones that are. For instance, if you are a food conglomerate with most of its agricultural activities in the global south, how will you need to reconfigure that for massive labor migration coming in the face of climate change? Do you have the cognitive technologies, including AI, data science and automation in place to make your supply chains more intelligent, agile and resilient?

You argue that China is an indispensable partner for any global systems redesign. How will leaders in the rest of the world need to reimagine their engagement with a rapidly aging and slowing China while navigating rising economic and military tensions?

Not every investment in China is bad and we’re not advocating for a wholesale withdrawal from all activities in China. That total decoupling is not desirable for anybody. In fact, there are lots of new opportunities for joint solutions that serve both our economic and national security interests as Americans and Chinese. Let’s talk about the fact that China’s coastal cities are as screwed as America’s cities are with sea levels rising. Hundreds of millions of people will be migrating north. That could mean joint investment in climate change mitigation and adaptation solutions, in new approaches to education, in regulating and managing migration, in innovation for public health and early pandemic detection and warning systems.

At some level, we’re going to get down to technologies that are sensitive, like chips and AI. And granted, you can weaponize almost anything these days. But there are technical ways to govern that, design protocols for dispute resolution and risk mitigation. We can watermark and forensically trace content, technical components and code. We can figure out where specialized microchips are going. We can put protocols in place to jointly identify and settle infractions and misunderstandings. It’s not perfect, to be sure. Nothing ever is. But we have to try, because the alternatives are even worse.

So there’s some optimism in your message?

I have a conviction that a lot of these problems are truly solvable with the right design. Executives need to get out there and try things with risk-bounded experiments. This is a craft you can learn. We give leaders a roadmap to lead people into a new future that’s better than one of distrust, fear, and fragmentation.