Ahead of ClimateCAP Summit, Haas sustainability leaders provide roadmap for training climate leaders

*Updated March 16

Former Fed Economist and Prof. James Wilcox is a longtime observer of federal fiscal policy, monetary policy, and the economy. A professor of finance and economic analysis and policy, Wilcox served as a senior economist on the President’s Council of Economic Advisors from 1990 to 1991, as an economist with the Federal Reserve from 1991 to 1992, and as chief economist for the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency from 1999 to 2001. His research focuses on small business lending, banking, and consumer spending.

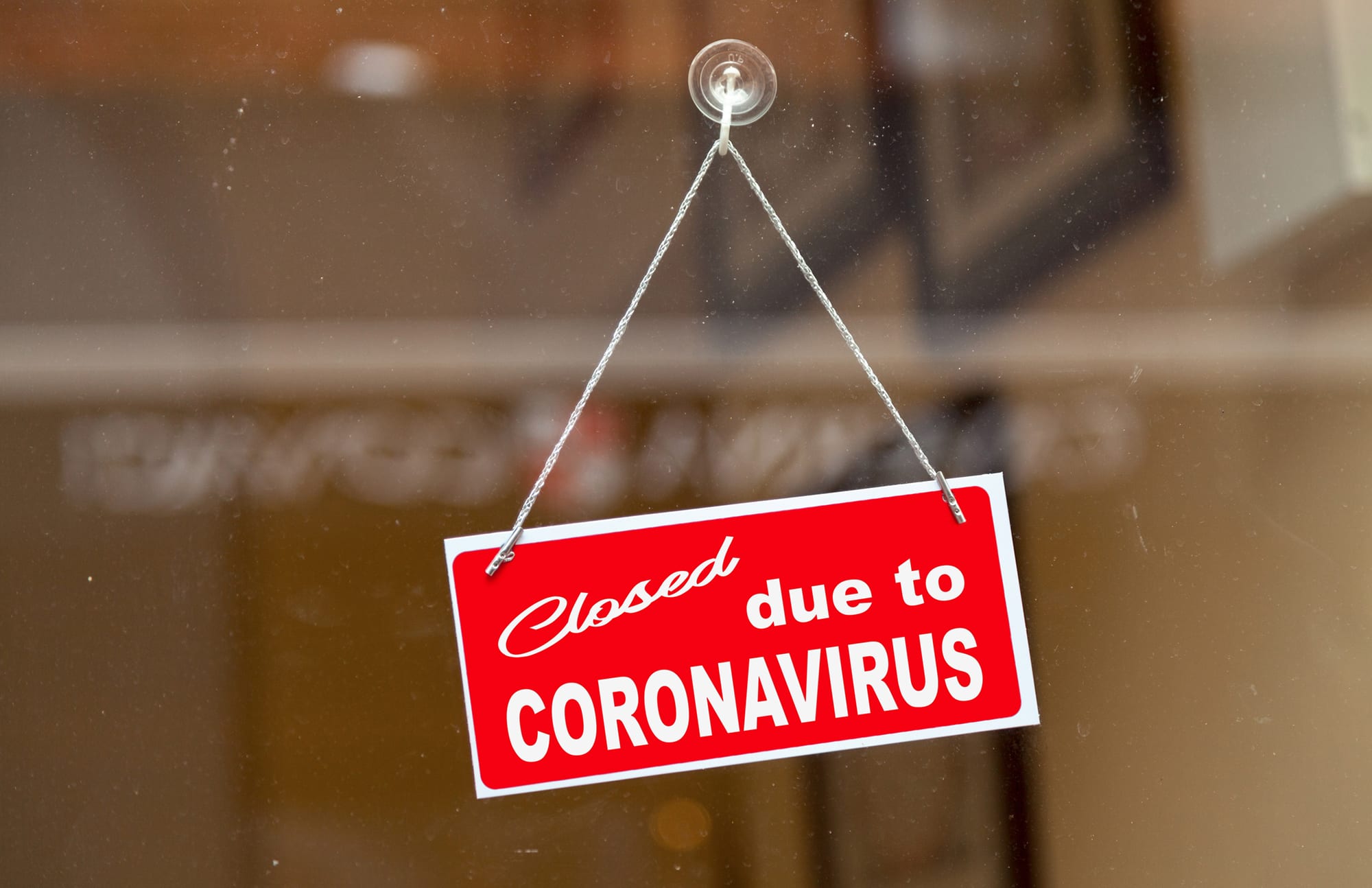

Wilcox shared his perspective on the week’s stock market whiplash as well as what the Fed and the government can do to cushion the widening economic crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

President Trump on Friday declared a national emergency that will free up $50 billion in aid, and stocks mostly bounced back from Thursday’s crash. Will the national emergency status help economically?

The emergency declaration allows for some helpful actions right away. Much more will need to be done. The declaration was also valuable if it signals that the Administration will be doing much more than it has so far. We have a serious problem. It calls for large, rapid responses.

The Administration can help by using fiscal policies now. Speed counts. The old saying that ‘a stitch in time saves nine’ holds for financial markets, businesses, and households if they have their operations or cash flows disrupted. Getting more help sooner to those who are more impacted can avoid more pain for them and can avoid taxpayers’ paying more to help more later.

The sooner the government acts, the better—and the cheaper—it will be for all of us.

The House passed a coronavirus emergency relief bill Friday night that includes two weeks of paid sick leave for some workers and up to three months of paid family and medical leave, $1 billion in grants to states to help pay unemployment insurance, and some food assistance. The Senate will take it up this week. What kind of policies do you think are most needed right now?

We want to get the most immediate help to those facing the most pressing pains. If supplies and demands contract as much as now seems likely, there will be real cash crunches for some big and small businesses, for higher-income households and lower-income households. Some businesses will have serious shortages of customers, and perhaps of materials and parts as well. Some households will have their hours or jobs cut. They may face serious cash, or liquidity, shortfalls—they may become “ill-liquid.” Policies should be adopted now that will be ready and able to provide financial triage. When illiquidity turns into insolvency, it causes many more problems. The sooner they can get help, the less they will need—’a stitch in time.’

One policy that could greatly help is government loan guarantees. The law passed about two weeks ago authorizes about $50 billion more SBA-guaranteed loans to small businesses harmed by the virus crisis. And some much larger companies may warrant help too. Most visibly being hammered by the corona crisis are airlines, hotels, and, of course, cruise companies. They won’t be the only ones. This emergency may well call for a program akin to a Large Business Administration that can quickly provide funds for large businesses.

These policies can be really valuable to businesses and households. They can also benefit the nation. Nonetheless, they do impose costs and risks on taxpayers. Hard-headed, helpful policies need not be give-aways like tax breaks. For example, a payroll tax cut—which has been discussed—is aimed at entirely the wrong group of people. To be paying payroll taxes you need to be working. It is the businesses that are hurt by this crisis and cannot afford to keep employees that we should aim at. We want to help the workers who have lost hours or jobs, and the businesses that are in danger of going under.

Policies funded by taxpayers can be more like investments. In the 2008 financial crisis, taxpayers got too little in return for the enormous costs and risks their government took on their behalf.

It’s not inevitable, but a recession now appears pretty likely for the U.S. economy.

Last week you commented that “darkening clouds have now come over the economy.” Is a recession inevitable at this point?

It’s not inevitable, but a recession now appears pretty likely for the U.S. economy. The more nations that impose widespread restrictions like lockdowns, the more likely that we have a global recession.

With appropriate policies, a recession in the U.S. could be shorter and shallower than usual. A lot depends on how the virus situation is handled and proceeds. At this point, forecasting the economy requires a guess about how effectively medical tests get distributed and used, how well our medical system can handle the volume of patients requiring some or a lot of care, and so on. I really don’t know much about the severity or probabilities of the various virus scenarios. Even forecasting what policies will get enacted is problematic.

But, anyone’s forecast for the economy will have to change if we keep getting surprises, good or bad, about the policies and management of the corona crisis. The larger and the sooner our fiscal response, the less likely that we have a recession this year or next. The early performance on health and economic policies has not been good, but they both show signs of improving.

Why do you say a recession could be shallower and shorter this time (with that big if)?

It is our good luck that the virus arrived here when our economy is on very solid footing. There have been few serious excesses, imbalances, or problems. Growth has been steady and unemployment low. We haven’t had a recession in over a decade. If the economy were ever going to withstand a shock, this is one of the better times. The job market has been very strong. Households’ finances have improved greatly. Housing has been strong. The same applies to businesses. After-tax profits have been very strong for a very long time. Even state and local government budgets have been in good shape lately. And, the financial system is really solid. Unlike the 2008 financial crisis, when problems erupted in—and were made worse by—financial institutions, this time around, the financial sector is in very solid shape. It’s strong enough to cushion some of the jolt to households and businesses. In the previous crisis, instead of being shock absorbers, financial institutions did the shocking.

Unlike the 2008 financial crisis, when problems erupted in—and were made worse by—financial institutions, this time around, the financial sector is in very solid shape.

Yet last week, stocks were crashing, and bond yields weren’t rising as they usually do. That led some to say the system is more fragile than it appears. What was going on?

The size and suddenness of the recent stock market declines built up some frictions in financial markets, especially in credit markets. That’s why the Federal Reserve was right to pledge an essentially unlimited availability of cash for financial markets to borrow. The Fed has also jumped in to buy lots of longer-term Treasurys when it appeared that even those bonds were suffering from illiquidity. These two operations have both lubricated the frictions in credit markets and signaled that it’s ready to act quickly and decisively if need be. The result is that borrowing rates will be lower than if the Fed had not acted.

The Fed is expected to drop interest rates to zero. How much will interest rate cuts help stem the crisis?

*Update: The Fed cut interest rates to near zero in an emergency move Sunday.

The Fed cut interest rates by half a percent just a short time ago. And, now there is a very good chance that it will just cut short-term rates to zero. Every little bit helps. And longer-term rates are now much lower than they were over the past year. Mortgage rates are down by a full percentage point. And that has already touched off a refinancing boom that will leave homeowners with more to spend elsewhere. The lower rates may also draw in more home buyers, too.

The Fed has done what it should do, which is lubricate and reassure financial markets, and the rest of us. But there are real limits to what it can do. In this situation, lower interest rates will not be the solution for workers who lose hours or jobs, or for businesses that lose customers. Making funds available to those who are cash-strapped will be. Whether assistance comes via paid sick leave, unemployment checks, government-guaranteed loans, or some other form is the province of fiscal policy. The sooner the government acts, the better—and the cheaper—it will be for all of us.

Posted in:

Topics: