On the night of Feb. 23, 2022, Anastassia Fedyk was at home, playing with her young son and prepping to teach the next morning, while her husband made homemade pasta for dinner.

“My grandmother was visiting us from Ukraine, and she started getting text messages from my sister in London, saying, ‘Have you seen what’s happening? This is unbelievable,’” she recalls.

What was happening was the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the country where Fedyk, an assistant professor of finance at Berkeley Haas, was born. Russia had made a move on the capital Kyiv and was shelling the city.

It wasn’t totally unexpected—like her entire family, Fedyk had been watching the troop buildup on the Russian border. But the severity of the attack on Kyiv took everyone by surprise. In the days that followed, Fedyk began to think what she could do to help.

Getting to work

Her first answer was to start writing. That was the impetus behind Economists for Ukraine, a group that she co-founded with Yuriy Gorodnichenko, a UC Berkeley professor of economics, along with colleagues from Columbia, University of Illinois and elsewhere. As economists, they hoped they could use their expertise to guide policy and public opinion in support of Ukraine.

“The more we wrote, the more it was seen, and the more there was demand for our writing,” she says. “We didn’t have newspapers knocking on our doors asking for op-eds early on, but we just keep writing, and soon we established an important voice.”

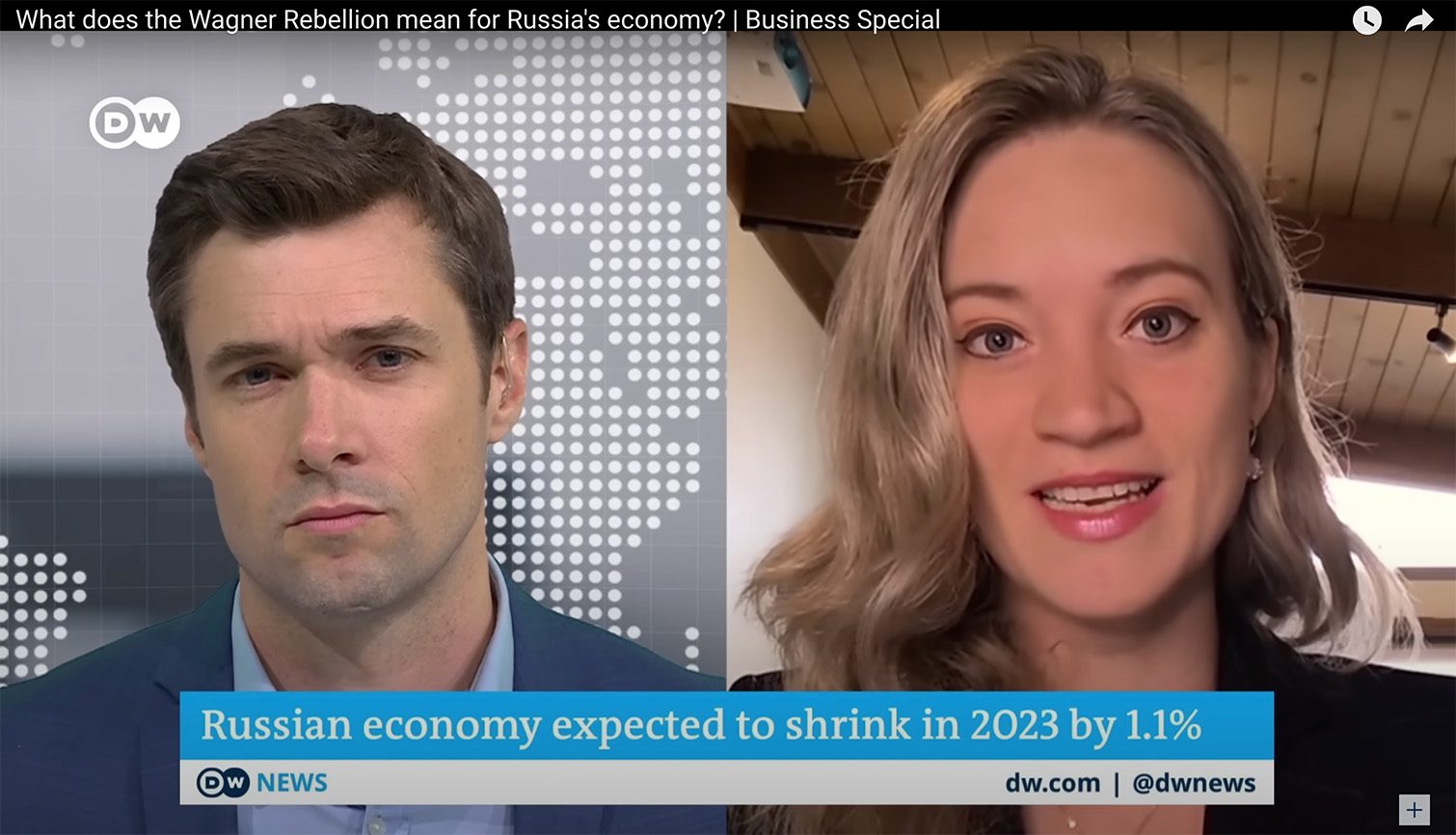

Their work paid off; Fedyk and the group’s writings on Ukraine have been featured in The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times and Project Syndicate. Fedyk has also been in-demand internationally for media interviews on the war’s economic impacts, making multiple appearances on CNN, the U.K.’s BBC, Germany’s Deutsche Welle, and more. By banding together with other economists, Fedyk and her colleagues have been able to guide policy as part of the influential Yermak-McFaul International Working Group on Russian Sanctions, and to offer thought leadership on the eventual reconstruction of Ukraine.

Human and AI-powered aid

Fedyk didn’t stop there. She teamed up with her husband, James Hodson, to launch LifeForce, a platform that takes an economics-based approach to humanitarian aid. Rather than just deliver goods that might not even be needed, LifeForce relies on staff on the ground to continuously check on inventories of important goods, with real-time updates.

“You can basically say, ‘I need insulin,’ and it will tell you which pharmacy near you has insulin and where you can go where you’re not going to be shelled while you’re walking there,” explains Hodson, the CEO of the AI for Good Foundation, which serves as the parent organization for LifeForce. “We’re not going to send you to a pharmacy that’s closed and we’re not going to send you to a pharmacy that doesn’t have the medicine that you need.”

It’s a way of matching needs to resources, Fedyk says. “It’s a very classical economics idea,” she says.

During the winter, Lifeforce also set up warming centers with electricity.

“When the infrastructure damage started in the fall, we set up shelters with internet and heating so that at least people could stay warm and connected during extended outages,” Fedyk says. “Otherwise, when there’s no electricity, there’s no Wi-Fi.”

Witnesses to war

Another initiative Fedyk and Hodson launched is Svidok, a site that acts as a living memorial and a repository for testimony of the lived experience of the war. An anonymous platform, it allows Ukrainians to tell their stories as well as document war crimes and atrocities.

“You need to be able to make a place where people can record their experience,” Fedyk says. “Not just the hard facts for the prosecution, but the lived experiences.”

So far, more than 3,000 Ukrainians—many of them teenagers and young adults—have added journal entries to the site, which has become the largest repository of written testimonies of the war. The posts describe harrowing experiences like hiding in basements and bathrooms during missile attacks, stories by girls and women who say they were raped by Russian soldiers, accounts from survivors of Russian prisons set up on occupied Ukrainian territory, and also descriptions of the tedium of living through endless winter blackouts. Svidok has partnered with the Ministry of Culture and every regional government in Ukraine, and content from the platform has been displayed in exhibits in the U.S. Congress and Poland’s Consulate General.

Teaching and research

At the same time, Fedyk has remained an engaged teacher, leading Haas core finance classes in the evening and executive MBA programs and helping launch the new Flex-MBA program. In June, she was named to Poets&Quants’ 2023 Best 40-Under-40 MBA Professors list.

She’s also a passionate researcher: Her most recent work looks at what happens when firms invest in AI. Surprisingly, employment doesn’t drop, she found. “Firms that invest in AI are producing more, they’re scaling up their operations, but they’re also hiring more employees, especially people like product managers to help manage that expanded product variety,” she explained.

From Ukraine to Berkeley

Fedyk moved to the U.S. when she was ten, when her parents were pursing higher degrees in finance and accounting. She went to high school in the Bay Area while her mother earned her PhD at Berkeley Haas.

“We lived in the university housing for students who have families—a very academic life,” she says. “Even as a kid here in Berkeley, I used to come to some of the seminars and classes with my mom. I guess I was always on the path of becoming an academic economist.”

After an undergraduate degree at Princeton, where she met her future husband on the very first day, followed by a stint at Goldman Sachs and a PhD at Harvard, she was able to come back to Berkeley, this time as a professor—her “dream job.”

“Moving back was like coming home,” she says.

Long road ahead

But her connection to Ukraine—her first home—runs deep. Some of her happiest memories are the summers she and her sister spent there after they moved to the U.S., at her grandma’s apartment in Chernivtsi.

She feels fortunate that her grandmother was visiting when the war broke out, and that she’s been able to make her home in Fedyk’s house for the past year and a half. Fedyk happy that her beloved grandmother is safe, but she longs to return to those old family reunions in a peaceful, prospering Ukraine.

There’s a long road ahead that will require a military victory for Ukraine, supporting humanitarian and economic needs in the war’s aftermath, and eventually rebuilding. But the lesson that Fedyk says she has taken away from her work supporting Ukraine is how much of a difference she could make through civic engagement.

“Ukrainians impressed the world with their bravery, but behind that bravery is a decentralized, collective effort,” she says. “Ideas can grow into initiatives that touch thousands of lives, if only we are willing to invest the time and effort.”