In honor of Pride Month, we’re highlighting members of the LGBTQ community at Haas.

(Note: Emeric L. Kennard, who identifies as a queer, nonbinary, transgender person, uses the preferred pronoun “they.”)

Growing up, Emeric L. Kennard’s sleep-deprived father would hand them crayons and a pile of paper and they’d draw for hours.

That passion to make art never stopped for Kennard, who is also the experiential learning project coordinator for the Berkeley Haas MBA for Executives Program.

An award-winning visual artist and illustrator, Kennard’s art is informed by a love of reading—science fiction in particular—and their work contains magical elements like woodland creatures, horned demons, and moon-soaked ceremonies.

“The privilege of growing up surrounded by so much nature affected me profoundly,” said Kennard, who is from the Clackamas, Chinook, Atfalati, and Kalapuya territory, also known as Oregon’s Willamette Valley.

The privilege of growing up surrounded by so much nature affected me profoundly.

But for Kennard, a mixed race, third-generation Korean American, a youth spent in a white suburb was also alienating. “I grew up being called exotic,” they said. “Older white ladies told me I looked like an Indian princess.”

Arriving in the Bay Area seven years ago, Kennard said, “I had a radical reorientation with race in this culture of organizing and resistance to white supremacy.”

Kennard’s art explores sexuality and race in their illustrations, paintings, comics and zines, with subjects that intersect gender, bodily identity, science, environment, and cultural survival. Their work has exhibited locally and nationally, hung in Congressional halls, and been recognized by the Society of Illustrators. “There’s always a story being told,” Kennard said. “That’s what drew me to art school.”

Here Kennard describes a few of the stories behind some favorites.

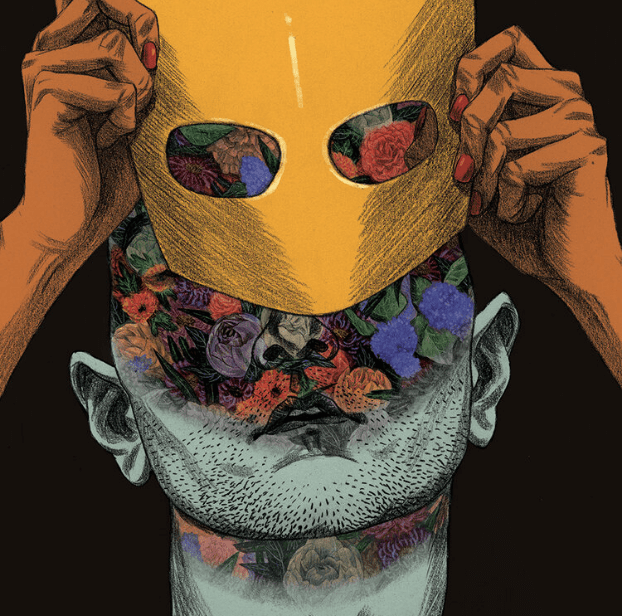

Ghost Stories

“This illustration for Mother Jones accompanied an article called Ghost Stories by Delilah Friedler, which was about hooking up while trans. There’s a beautiful end note in this article in which Delilah speaks to the potential for beauty that exists between trans women and cis men in relationships when men are capable and willing to engage with their own vulnerability and to engage with unlearning toxic masculinity, and embrace the love, the sexuality, whatever the relationship offers them that shame and homophobia and transphobia would otherwise block. And while the bulk of the article speaks more to the impact and the violence of that shame, which is very important to discuss, so many of the stories about trans people, they’re not authored by us and they’re about our deaths. Most of the time when you hear about a trans person in major news it’s because one of us has been harmed or killed, and disproportionately it’s Black trans women and trans women of color. It was really important to me to create an image that didn’t erase the reality of the pain that we experience, but also helped visualize this beautiful open door that Delilah points to at the end of her article, the potential that exists if we could collectively move past the shame. And so that is where the idea for the sense of reveal and removal, taking off a mask, came from.”

Willpower

“This mixed media piece was inspired by an article from the science magazine Nautilus. The original title of that article was Against Willpower. The article critiques the modern concept of willpower against the modern knowledge of psychology and how the human brain works, and makes a case that willpower as we have come to culturally understand it today is really repressive, and creates false and unobtainable goals of self control that are not actually healthy. While the article doesn’t explicitly address queer experience, there’s obviously a lot of connections that could be made. I thought about the experience of being closeted and the really harmful ideas that many people still hold that sexuality or gender can be fixed or need fixing, and the abuse that is conversion therapy. That was an immediate personal connection I made to the article, and I wanted to make an image that captured that sense of holding it down, keeping it in, trying to keep something that really wants and needs to be released repressed.”

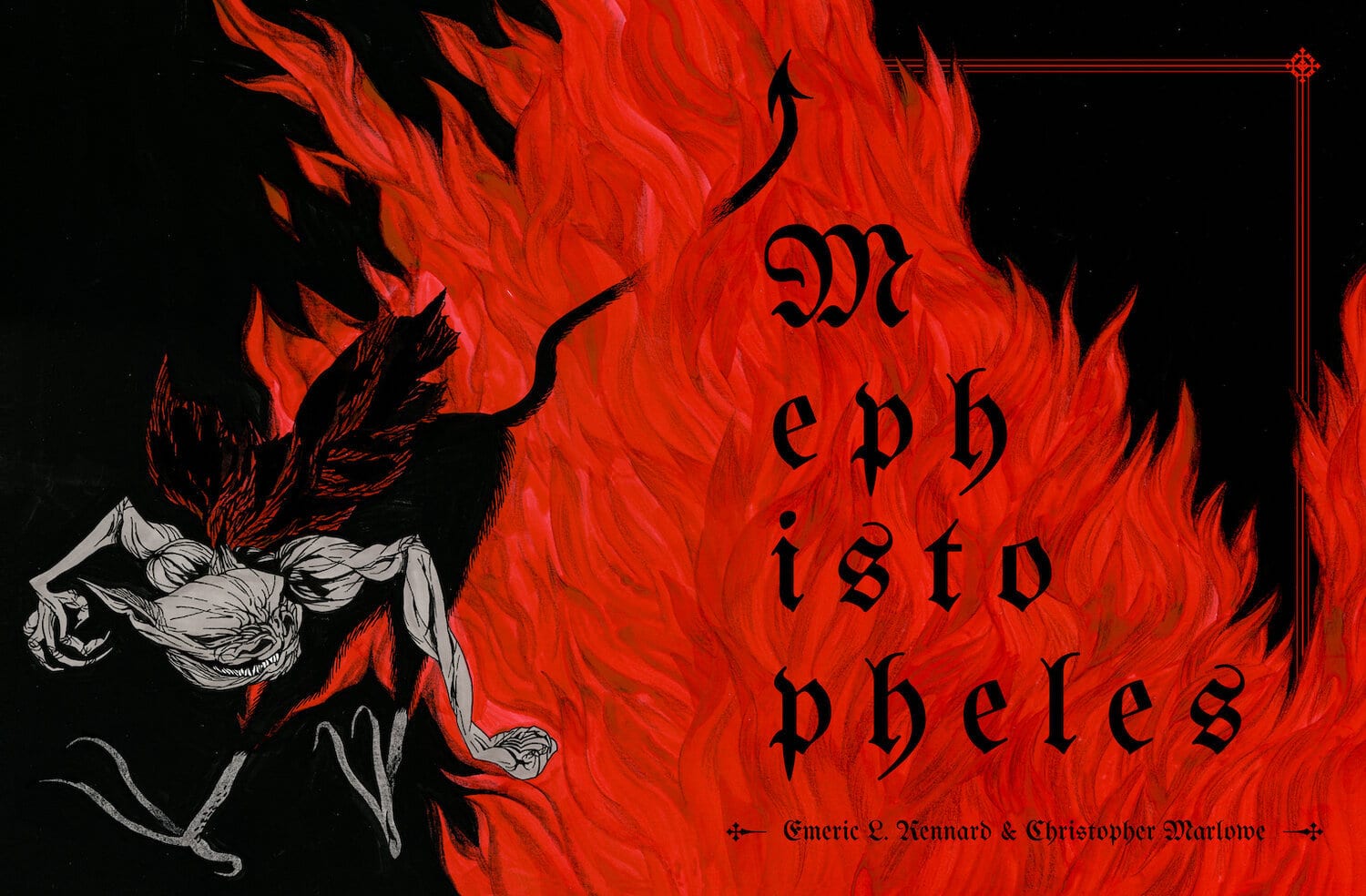

Mephistopheles

“This is an illustrated demon’s monologue about rebelling against tyranny and embracing one’s own power. It takes and remixes lines and words originally spoken by Mephistopheles and other demonic figures in Christopher Marlowe’s 16th century play The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Dr. Faustus.

There’s this one scene where Faustus summons Mephistopheles from hell. Faustus is trying to argue with Mephistopheles that hell isn’t real, which is absurd in the context of this play and this scene. And Mephistopheles is baffled and insulted. And while I don’t remember the exact lines, his response to Faustus in essence is, ‘I know hell is real because I have suffered through it and how dare you.’ And I had a really powerful moment of recognition that I didn’t expect in that scene where I saw in that exchange myself and I saw all of these interactions that I, and many of the trans people in my life, had had in real time with cisgender people who are trying to convince us as we’re standing in front of them that we’re not real.

It’s also true that part of the hurt of being unacknowledged as real is that often we are put through a great deal of suffering for being who we are. Regardless of our own relationship to our bodies, regardless of how we feel about our own lived experience, suffering is imposed upon us externally, and I really felt Mephistopheles in that scene. I had this deep sense of understanding and connection with his character.”

Burial

“This was a canvas painting, and I made it for this wonderful art show that I was invited into by friend and mentor Channing Joseph, a Black educator, journalist, advocate, member of the queer community, and just a phenomenal person.

The concept of the show, called Octavia’s Attic, was that Octavia Butler’s sci-fi novels were actually documentary accounts, because she could time travel, and she could visit alternative timelines and universes. What if this was recently discovered and made known to the public and her attic was opened up for public visit? What would it contain? I love this concept.

Around that time I’d learned a little bit more about gender expressions and identities in pre-colonized Korea that today we might consider queer—practices by what in English we call shamans; the Korean term is mudang. Often these roles were embodied by women, but not always, and there was this sacred femininity in these spiritual roles.

I was also learning more about queer relations in Korean royalty among men and women, and I had this idea of a queer funeral and a literal replanting. So much of my own access to this history is really limited. I didn’t learn Korean growing up, and even my halmeoni, my Korean grandmother, doesn’t know a lot of this. And so I was really compelled by this idea of planting a literal piece of someone and having them, through some spiritual process, grow and transform into a tree and be present as an ancestor as a living tree.”