Dan Frank Was a Gifted and Generous Editor

I don’t know how many people in the reading public would recognize the name Dan Frank. Millions of them should. He was a gifted editor, mentor, leader, and friend, who within the publishing world was renowned. His untimely death of cancer yesterday, at age 67, is a terrible loss especially for his family and colleagues, but also to a vast community of writers and to the reading public.

Minute by minute, and page by page, writers gripe about editors. Year by year, and book by book, we become aware of how profoundly we rely on them. Over the decades I have had the good fortune of working with a series of this era’s most talented and supportive book editors. Some day I’ll write about the whole sequence, which led me 20 years ago to Dan Frank. For now, I want to say how much Dan Frank meant to public discourse in our times, and how much he will be missed.

Dan started working in publishing in his 20s, after college and graduate school. While in his 30s he became editorial director at Viking Books. Among the celebrated books he edited and published there was Chaos: Making a New Science, by James Gleick, which was a runaway bestseller and a critical success. It also represented the sort of literary nonfiction (and fiction) that Dan would aspire to: well-informed, elegantly written, presenting complex subjects accessibly, helping readers enter and understand realms they had not known about before. As it happened, Gleick worked with Dan on all of his subsequent books, including his biographies of Richard Feynman and Isaac Newton, as well as Faster and The Information.

In 1991, after a shakeup at Pantheon, Dan Frank went there as an editor, and from 1996 onward he was Pantheon’s editorial director and leading force. As Reagan Arthur, the current head of the Knopf, Pantheon, and Schocken imprints at Penguin Random House, wrote yesterday in a note announcing Dan’s death:

During his tenure, Dan established Pantheon as an industry-leading publisher of narrative science, world literature, contemporary fiction, and graphic novels. Authors published under Dan were awarded two Pulitzer Prizes, several National Book Awards, numerous NBCC awards, and multiple Eisners [for graphic novels] ….

For decades, Dan has been the public face of Pantheon, setting the tone for the house and overseeing the list. He had an insatiable curiosity about life and, indeed, that curiosity informed many of his acquisitions. As important as the books he published and the authors he edited, Dan served as a mentor to younger colleagues, endlessly generous with his time and expertise. Famously soft-spoken, a “writer’s editor,” and in possession of a heartfelt laugh that would echo around the thirteenth floor, he was so identified with the imprint that some of his writers took to calling the place Dantheon.

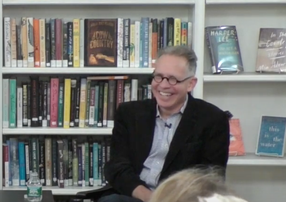

There are surprisingly few photos of Dan available online. I take that as an indication of his modesty; of the contrast between his high profile within the publishing world and his intentionally low profile outside it; and of his focus on the quiet, interior work of sitting down with manuscripts or talking with authors. The only YouTube segment I’ve found featuring him is this one from 2015, when Dan interviewed the author Thomas Mallon at the Center for Fiction in New York. (I am using this with the Center’s permission.)

Dan is seated at the right, with his trademark round glasses. The clip will give an idea of his demeanor, his gentle but probing curiosity, his intelligence and encouragement, his readiness to smile and give a supportive laugh. Watching him talk with Mallon reminds me of his bearing when we would talk in his office at Pantheon or at a nearby restaurant.

Everything that is frenzied and distracted in modern culture, Dan Frank was the opposite of. The surest way to get him to raise a skeptical eyebrow, when hearing a proposal for a new book, was to suggest some subject that was momentarily white-hot on the talk shows and breaking-news alerts. I know this firsthand. The book ideas he steered me away from, and kept me from wasting time on, represented guidance as crucial as what he offered on the four books I wrote for him, and the most recent one where he worked with me and my wife, Deb.

Dan knew that books have a long gestation time—research and reporting, thinking, writing, editing, unveiling them to the world. They required hard work from a lot of people, starting with the author and editor but extending to a much larger team. Therefore it seemed only fair to him that anything demanding this much effort should be written as if it had a chance to last. Very few books endure; hardly any get proper notice; but Dan wanted books that deserved to be read a year after they came out, or a decade, or longer, if people were to come across them.

The publisher’s long list of authors he worked with, which I’ll include at the bottom of this post, only begins to suggest his range. When I reached the final page of the new, gripping, epic-scale novel of modern China by Orville Schell, called My Old Home, it seemed inevitable that the author’s culminating word of thanks would be to his “wonderful, understated” editor, Dan Frank.

What, exactly, does an editor like this do to win such gratitude? Some part of it is “line editing”—cutting or moving a sentence, changing a word, flagging an awkward transition. Dan excelled at that, but it wasn’t his main editing gift. Like all good editors, he understood that the first response back to a writer, on seeing new material, must always and invariably be: “This will be great!” or “I think we’ve really got something here.” Then, like all good editors, Dan continued with the combination of questions, expansions, reductions, and encouragements that get writers to produce the best-feasible version of the idea they had in mind. Their role is like that of a football coach, with the pre-game plan and the halftime speech: They’re not playing the game themselves, but they’re helping the athletes do their best. Or like that of a parent or teacher, helping a young person avoid foreseeable mistakes.

You can read more about Dan Frank’s own views of the roles of author, editor, publisher, and agent, in this interview in 2009, from Riverrun Books. It even has a photo of him! And you can think about the books he fostered, edited, and helped create, if you consider this part of Reagan Arthur’s note:

Dan worked with writers who were published by both Pantheon and Knopf. His authors include Charles Baxter, Madison Smartt Bell, Alain de Botton, David Eagleman, Gretel Ehrlich, Joseph J. Ellis, James Fallows, James Gleick, Jonathan Haidt, Richard Holmes, Susan Jacoby, Ben Katchor, Daniel Kehlmann, Jill Lepore, Alan Lightman, Tom Mallon, Joseph Mitchell, Maria Popova, Oliver Sacks, Art Spiegelman, and many, many others.

Deb and I will always be grateful to have known Dan Frank, and to have worked with him. We send our condolences to his wife, Patty, and their sons and family. The whole reading public has benefited, much more than most people know, from his life and work.