Topic: Entrepreneurship

All is lost in San Francisco? City loyalists take issue with naysayers. Data may back them up

Side-stepping from Big Tech to direct impact

Dr. Victor Santiago Pineda, BS 02 – Enacting World-Wide Social Change

Berkeley SkyDeck: How this fast-growing entrepreneurship accelerator also drives the university’s public education mission

In a first, UC Berkeley showcasing startups around J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference

The most disruptive undergraduate business school startups of 2023

How to maneuver through a many-faceted MBA transition

Becoming a changemaker with Alex Budak

Traveling Spoon

Alumnae provide cultural exchange via food

Tastes and smells tell the stories of a place and people like nothing else. It’s an ethos that drove Aashi Vel and Stephanie Lawrence, both MBA 13, to form Traveling Spoon, a San Francisco-based food tourism business in which home cooks in 65 countries host travelers for authentic meals and cooking classes. Traveling Spoon also organizes local market tours. It’s about, as they say, “traveling off the eaten path.” Their mission is to create meaningful travel experiences, preserve culinary traditions, and provide income for locals. Here’s a look at their success.

Tastes and smells tell the stories of a place and people like nothing else. It’s an ethos that drove Aashi Vel and Stephanie Lawrence, both MBA 13, to form Traveling Spoon, a San Francisco-based food tourism business in which home cooks in 65 countries host travelers for authentic meals and cooking classes. Traveling Spoon also organizes local market tours. It’s about, as they say, “traveling off the eaten path.” Their mission is to create meaningful travel experiences, preserve culinary traditions, and provide income for locals. Here’s a look at their success.

2007

In China, Lawrence is disheartened by a “fairly touristy” dining experience. She moves to Beijing for six months, futilely searching for a Chinese grandmother who will teach her to make dumplings. Vel, in 2011, has similarly ungratifying food experiences in Mexico.

2011

During Haas orientation in August, Lawrence and Vel meet over pork tacos and bond over a shared passion for food and travel. They launch a pilot version of Traveling Spoon in December, booking customers for food explorations in India in January 2012.

2013

Traveling Spoon connects travelers with home cooks in Asia at first. Business Insider calls it one of “6 Silicon Valley startups launched in the last six months that could be huge.”

2014

The business receives $870,000 in funding, including from angel investor Erik Blachford, former CEO of online travel agency Expedia. Berkeley culinary doyenne Alice Waters is an advisor. Forbes dubs Traveling Spoon the Next Generation of Culinary Tourism.

2015

Traveling Spoon builds and automates an online marketplace and launches food experiences in 20 countries including Japan, Thailand, and Turkey.

2018

The company raises another round of funding with follow-on investment by lead investor Erik Blachford. Traveling Spoon also expands globally and scales host supply and traveler demand.

2020

Grounded by COVID, Traveling Spoon goes online, allowing armchair travelers to learn how to make dishes like noodle soup and injera from home cooks in exotic locales like Mongolia and Ethiopia. The virtual classes continue today.

2022

The business, which Forbes calls “the Airbnb for foodies,” expands to 65 countries, from Albania to Vietnam.

Wayfinders

The Haas connections that help alumni reimagine business.

Members of the Haas community have been reimagining business for 125 years. But how do fresh ideas and strong determination turn into novel business practices? Well, for one thing, no one breaks new ground in a vacuum. Here, we celebrate some recent graduates aiming to change the world for the better and the members of the Haas community who helped them take their problem-solving to the next level. Their assistance runs the gamut: from a simple introduction or piece of advice to help securing crucial funding. Whatever the support, it was the connection these alumni needed to begin reimagining business.

Bringing Artistry to Venture Capital

Asha Culhane-Husain, BS 18

“I believe that entrepreneurs are artists,” says Asha Culhane-Husain. It’s not surprising she emphasizes the artistic side of entrepreneurship: As a business student, Culhane-Husain also double-majored in theater, dance, and performance studies. Now she’s using her diverse talents to infuse artistry into venture capital.

While at Haas, Culhane-Husain interned at a VC firm and thought she might work there after graduation. But being awarded Haas’ Thomas Tusher Scholarship for Study Abroad her junior year changed her life. The scholarship, sponsored by Thomas Tusher, BA 63 (political science), the retired president and COO of Levi Strauss & Co., was created after Tusher’s own “life-altering” study-abroad experience led him to a career in international business. “Not only has Asha turned her time abroad into a unique career trajectory,” says Tusher, “but she’s taken that experience to a new level.”

Culhane-Husain attended Ireland’s National Theater School. After graduating from Haas, she spent three years at France’s national drama academy, the Conservatoire National Supérieur d’Art Dramatique, where she gained extensive conservatory training. She now works as a writer, producer, filmmaker, and actor, yet she remained interested in VC and began to explore how she might apply her artistic talents in the business world.

“In venture capital, the early rounds of funding are largely based on stories—on the team and the idea—because they don’t yet have data,” Culhane-Husain says. And while CEOs are the experts of their field and product, they don’t always have the tools to tell their company’s story effectively—which can mean the difference between securing early-stage funding or not. What if she could help them deliver a pitch that would seal the deal?

Culhane-Husain teaches speakers to…communicate effectively and captivate a boardroom or audience.

Her former Haas instructor Stephen Etter, BS 83, MBA 89 (shown right), had never heard of anyone doing what she was proposing. “I’ve been teaching for 27 years, and no day has there been such a talented individual in arts and business,” he says of Culhane-Husain.

This past year, Culhane-Husain worked with the same VC firm where she once interned, helping management teams use their natural strengths to deliver an effective pitch. Much like a director would bring out the abilities of an actor, Culhane-Husain teaches speakers to control the timbre of their voice, rhythm of speech, and body position to communicate effectively and captivate a boardroom or audience.

Culhane-Husain is forging her path as she goes. The Tusher Scholarship supported her in pursuing her artistic passion, and now, consulting for the VC firm, she gets to combine her skills in business and the arts. “It’s all coming full circle,” she says

Making Four-Year Colleges Accessible

Manny Smith, MBA 21

Community colleges were intended to be an on-ramp to a bachelor’s degree for millions of American students. But as Manny Smith (shown left) discovered, the transfer process from a community college to a four-year institution is broken. So he founded EdVisorly to fix it.

Smith didn’t attend community college himself, but he was a first-generation student, and college was never a given. He was offered an appointment to the U.S. Air Force Academy, which included a scholarship and a career path as an Air Force officer. He jumped at the opportunity.

After Smith graduated, his commission included developing technology for the Air Force and Space Force. In 2018, he accompanied a friend to a conference focused on services to support community college students. There he learned how hard it is for talented and motivated students to eventually complete a bachelor’s degree. Across 5 million U.S. community college students who want to obtain a bachelor’s, Smith says, only 2.4% will transfer to a four-year university within two years of beginning their education.

One reason is that the transfer process is complicated: Admissions requirements vary from school to school, and there are few reliable resources for community college students. EdVisorly seeks to bridge the gaps students face through its innovative approach and partnerships with university enrollment teams.

There are few reliable transfer resources for community college students. EdVisorly seeks to bridge the gaps.

On EdVisorly, students can easily connect with admissions teams at universities, discover transfer requirements, create a transfer plan, and apply to schools.

Six months after he began building EdVisorly, Smith took an entrepreneurship class with Kurt Beyer (shown left), which was pivotal. “I knew Dr. Beyer’s class would be catalyzing and provide a foundation for our company to thrive,” Smith says. Beyer, a Navy veteran, emphasized a lot of the principles Smith gained from his military training as being invaluable in starting a company.

This year, EdVisorly received funding from the California Innovation Fund, which invests solely in UC alumni and which Beyer founded. Beyer says he recognized in Smith the makings of a successful founder. “As a former Air Force officer, Manny brought far more leadership acumen than many MBA students. That military background makes him an outstanding entrepreneur.”

With the latest round of funding, EdVisorly is expanding its partnerships across four-year universities nationwide to help more community college students earn their bachelor’s degrees and realize the many opportunities that come with them.

Helping Clean Technologies Break Through

Harshita Mira Venkatesh, MBA 21

In many industries, the climate crisis demands new ways of doing things. That’s why Harshita Mira Venkatesh has spent the last two years working to bring some of the most promising cleantech innovations to market as a business fellow at Breakthrough Energy, an umbrella organization founded by Bill Gates. This multi-arm organization is working to develop and accelerate climate solutions in sectors that are particularly hard to decarbonize: think steel, heating, transportation, and food. The focus, Venkatesh explains, “is on technologies that at scale can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by half a gigaton a year or 1% of greenhouse gas emissions annually.”

For Venkatesh, it all started with a simple introduction. She’s always cared deeply about the climate crisis, but before coming to Haas, she had no direct climate experience. That changed when she took Cleantech to Market, an experiential, interdisciplinary program that brings together graduate students from across campus to help entrepreneurs nationwide commercialize emerging cleantech solutions. Each year, C2M Co-director Brian Steel (shown right) invites speakers to talk to the class, and that year, he asked Ashley Grosh, the director of Breakthrough Energy’s Fellows Program, to discuss funding climate solutions.

Venkatesh was intrigued by Grosh’s presentation, and she asked Steel if he would introduce her. Steel was only too happy to oblige. “Harshita clearly realized that this was one of those moments that if left unappreciated for its potential significance would pass her by,” he says. “And she didn’t let that happen.”

Venkatesh and Grosh discussed the Fellows Program, which was just getting off the ground. Later, when Grosh sought input from Steel, he gave Venkatesh a ringing endorsement.

Breakthrough Energy’s Fellows Program pairs two groups of fellows: scientists and engineers who have a climate technology to commercialize and businesspeople like Venkatesh, who use their expertise to help innovators de-risk their technology so it’s marketable. “It’s like Cleantech to Market on steroids,” Venkatesh says. While at Breakthrough Energy, she worked with a pioneering green cement company to develop its go-to-market strategy and helped a climate-friendly ammonia company research beachhead markets and supply chains.

As part of the program’s inaugural cohort, Venkatesh’s two-year tenure ended in September. Now she’s looking forward to her next role and continuing to support climate tech innovations.

Reimagining Online Reviews

Reimagining Online Reviews

Michael Ebel, MBA 17

Working as a bartender while an undergraduate, Michael Ebel (shown left) saw the power of review sites like Trip Advisor and Yelp. Specifically, he noted the outsized impact a bad review can have on the bottom lines of small businesses. “The average person has a good experience and doesn’t do anything,” Ebel says. “But if they have a bad experience, they run online seeking retribution.”

Ebel thought there had to be a better way, and several years later, while working at Meta, he realized video was it. That epiphany gave birth to Atmosfy, an app that allows users to share videos of their experiences at local businesses so people can see for themselves what an establishment is like.

Atmosfy launched at the height of the pandemic, a period that was brutal for small businesses. “We thought, if we could get people in San Francisco to take a video of a good experience and say, ‘Hey, this place is still open, come on down and support it,’ wouldn’t that be a difference maker?” says Ebel. “And that is the core mission that kicked us off.”

Atmosfy is a deeply Haas-centric startup. “In almost any helpful dimension you can imagine, we have leveraged that from Haas,” Ebel says. Professor Toby Stuart (shown right) has been a particularly valuable resource. Stuart offered advice and made crucial introductions that helped Ebel secure financing. “Toby was instrumental in helping us think about strategically raising our first round and how to avoid the various pitfalls of fundraising,” Ebel says. “He also provided sound advice on how to build a world-class team that would be critical to our success.”

By the time Ebel called Stuart to talk about Atmosfy, he’d already made enormous progress on an alpha version of the app. Stuart was impressed by how much he’d accomplished. “Usually someone wants to outsource thinking; they come by with a half-baked idea and before making much headway,” Stuart says. “But Michael had done a lot, and he did it on very little money. He demonstrated a ton of conviction and an incredible work ethic.” Stuart also noticed that Ebel never said “I,” he always used the pronoun “we” even though he was a solo founder working mostly on his own. “I thought that was a great sign for someone who’s going to build and lead a team,” Stuart says.

And that team has grown rapidly. Atmosfy is now in 150 countries, showcasing restaurants, bars, and hotels in 10,000 cities. And no doubt more are on the way. In August the company raised $14 million in seed funding, led by Redpoint Ventures.

Editor’s note: In February 2024, Atmosfy was named to Business Insider‘s list of 18 startups disrupting the social media scene with alternative ways to connect online.

Putting Homebuyers in the Driver’s Seat

Matt Parker, EMBA 23

If you’re looking to buy a home, the first order of business is hiring a real estate agent, right? Not necessarily. Matt Parker, the co-founder and CEO of Alokee, wants to transform the real estate landscape by enabling people to buy a home without the expense of an agent. Parker, who founded the company with five Haas classmates, has worked as a real estate agent, so he knows the industry’s downsides. “The way the system is structured, all the business models are based on selling as many homes as fast as possible,” he says. The buyer’s best interest isn’t necessarily a priority.

Alokee is a virtual real estate agent designed for DIYers who may not need an intermediary when shopping for a home.

Alokee wants to change that. Using AI, automation, and the founders’ expertise, Alokee is a virtual real estate agent designed for do-it-yourselfers who may not need an intermediary when shopping for a home. Everything you’d call an agent for, you can do yourself with Alokee, Parker says. “Instead of asking someone when you can view a home, you simply set up a tour. Instead of asking someone to make an offer for you, you just make an offer.” For some buyers, the whole process can be wrapped up in a day. For those who want more help, Alokee provides expert advice from a real estate attorney. The company, currently operating in California with plans to expand, charges a flat fee, which ends up saving buyers a lot of money.

With an all-Haas startup team, the community’s DNA is embedded in the company, and input from Haas advisors is also woven in. Parker and his co-founders were working on Alokee while they took two classes with professional faculty member Maura O’Neill, BCEMBA 04, who instantly knew they had a winning idea. “That part of real estate was just waiting to be disrupted,” O’Neill says. “And here was somebody who actually had the knowledge and had been smart about putting the team together with different kinds of expertise.”

Parker says O’Neill’s vast experience as a serial entrepreneur was indispensable. Yet he says what mattered most was her continual motivation. “She understands that being an entrepreneur is hard. You have these valleys, and Maura is right there telling you these valleys are part of the process.” She told Parker what they were doing well and where they needed to up their game.

Earlier this year, O’Neill and her son were in the market to buy a family house in Oakland, and they used Alokee. “I became the biggest fan imaginable,” she says.

Jackson Block, BS 17

CEO and Co-founder, LGBT+ VC

Soon after the 2022 Club Q massacre in Colorado Springs, Colorado, Jackson Block took action to advance LGBTQ+ investment and support.

Soon after the 2022 Club Q massacre in Colorado Springs, Colorado, Jackson Block took action to advance LGBTQ+ investment and support.

He joined forces with Tiana Tukes, both of whom are members of the LGBTQ+ and venture capital communities, and launched LGBT+ VC, a nonprofit providing opportunities to underrepresented communities in venture capital. It’s work that’s greatly needed, Block says.

“In this past year alone, there have been 650 anti-LGBTQ bills in 46 states, yet there’s been nothing said from the VC community.”

Block notes that while a large percentage of the country’s GDP comes from venture-backed businesses, less than 1% of VC funding goes to LGBTQ+ founders. “Our goal is to make more investors,” he says. “We’re not going to break the patterns until we focus on the supply side of the issue.” To do that, LGBT+ VC is providing access to networks, information, and capital and helping LGBTQ individuals become angels, investors, scouts, and limited partners.

Block says his Berkeley and Haas connections have helped him launch his business. He’s a board member of the Haas Alumni Network’s NYC Chapter and says the group has been consistently supportive. Last June, LGBT+ VC held its inaugural summit in New York, convening more than 500 VC and tech leaders to discuss the future of finance. It was one giant step toward reimagining business that benefits the global LGBTQ+ community.

Priya Saiprasad, BS 10

Co-Founder and General Partner, Touring Capital

Priya Saiprasad often doesn’t look like other venture capitalists in Silicon Valley boardrooms. But she does look like the consumers of many products under consideration for funding—a perspective that adds value to the discussions happening.

Priya Saiprasad often doesn’t look like other venture capitalists in Silicon Valley boardrooms. But she does look like the consumers of many products under consideration for funding—a perspective that adds value to the discussions happening.

“I bring to the table diverse perspectives that represent Millennials, women, entreprenuership, and a global-mindset that others might not have thought of,” says Saiprasad, who lived in 12 countries as a child.

As co-founder and general partner of Touring Capital, a new venture firm focused on AI software, Saiprasad aims to break the mold of venture funds. “I have many thoughts on how to solve for the systemic biases that exist in venture, how to create a firm that’s founder-first, and how to leverage advancements in AI for the next generation of software productivity.”

A veteran in AI software investment, Saiprasad was primed for her new role. Her experiences at Microsoft’s venture fund M12, Mayfield Fund, and SoftBank Investment Advisers provided insights on creating a cutting-edge yet enduring fund, she says. So when longtime mentor Nagraj Kashyap, an M12 alumnus, approached her about founding a firm with an AI focus, she jumped at the chance.

“Advancements in AI have been happening over the last decade and now they’re finally at a precipice of reaching massive scale and adoption,” she says.

As digital natives, Millennials like Saiprasad are leading the expectations for what AI and other emerging technologies should do. So while she might not look like many in the boardroom today, she certainly looks like the future.

UC LAUNCH teams gear up for Demo Day pitches

Student-led startup teams tackling a diverse range of challenges—from carbon emissions to the use of AI in education—will come together to pitch this week at the University of California LAUNCH Accelerator’s Fall 2023 Demo Day.

The event, a chance for startups to pitch their ventures to a panel of judges, will be held Thursday, Nov. 30, at Spieker Forum in Chou Hall. All eight finalists will compete for up to $50,000 in non-dilutive funding.

Rhonda Shrader, MBA 96, executive director of the Berkeley Haas Entrepreneurship Program, noted the strong turnout of women this year.

“For the first time in UC LAUNCH history, seven of the eight finalists have at least one female co-founder,” she said. “We are super excited to celebrate them on Demo Day.”

Scaling a company

The UC LAUNCH program guides students through the steps of scaling a company using the lean methodology, with mentorship provided by experts in the field. All teams must include at least one current UC student, alum, or faculty member. More than 250 startups that have participated in the program have gone on to raise more than $1.4 billion collectively, according to UC LAUNCH organizers.

This year’s finalists include CarbonSustain, providing a way for companies to efficiently track and analyze carbon emissions.

Co-founder Paul Bryzek, MBA 24, said the team interviewed more than 85 potential customers, competitors, business owners, and subject matter experts while in UC LAUNCH. “Our interviews yielded 10 potential customers, three distinct customer target groups, an understanding of their willingness to pay, and gaps with the existing solutions,” he said. “We’re grateful for the mentorship from Rhonda Shrader and the UC LAUNCH volunteers who helped us to achieve product-market fit.”

Finalist Rumi’s platform helps schools integrate AI to enhance student learning through writing.

Co-founder Mohammad Hossein Ghasemzadeh, MIMS 16, said the team did extensive research in forming the startup and believes that AI will play a key role in the future of education. “We’ve talked with over 150 instructors across the country, and we’re very excited to share our story and provide some insights into what the future of AI in education will look like,” he said.

Eight finalists pitching

Other LAUNCH finalists include OmBiome, a regenerative health company creating algae-based products for oral and gut health; Rely, simplifying property management for landlords and offers renters a comprehensive real estate meta-search engine; Materri, a materials marketplace focused on sustainable materials for footwear and apparel; Insta Chef, which is providing nutritious, easy-to-prepare meals to senior living facilities; Essence Labs, an AI-powered platform optimizing work schedules for female employees based on hormonal cycles; and AidRx, providing custom AI charting solutions to ease the documentation burden for pharmacists and other non physician clinicians.

The judging panel includes Ben Goldfein of WilmerHale, Jed Katz of Javelin Venture Partners, and Kat Mañalac of Y Combinator.

Are You an Aspiring Entrepreneur? Here’s How to Take Advantage of Your Business Major at Haas

Japan’s top economic minister visits Berkeley Haas to spur innovation, collaboration

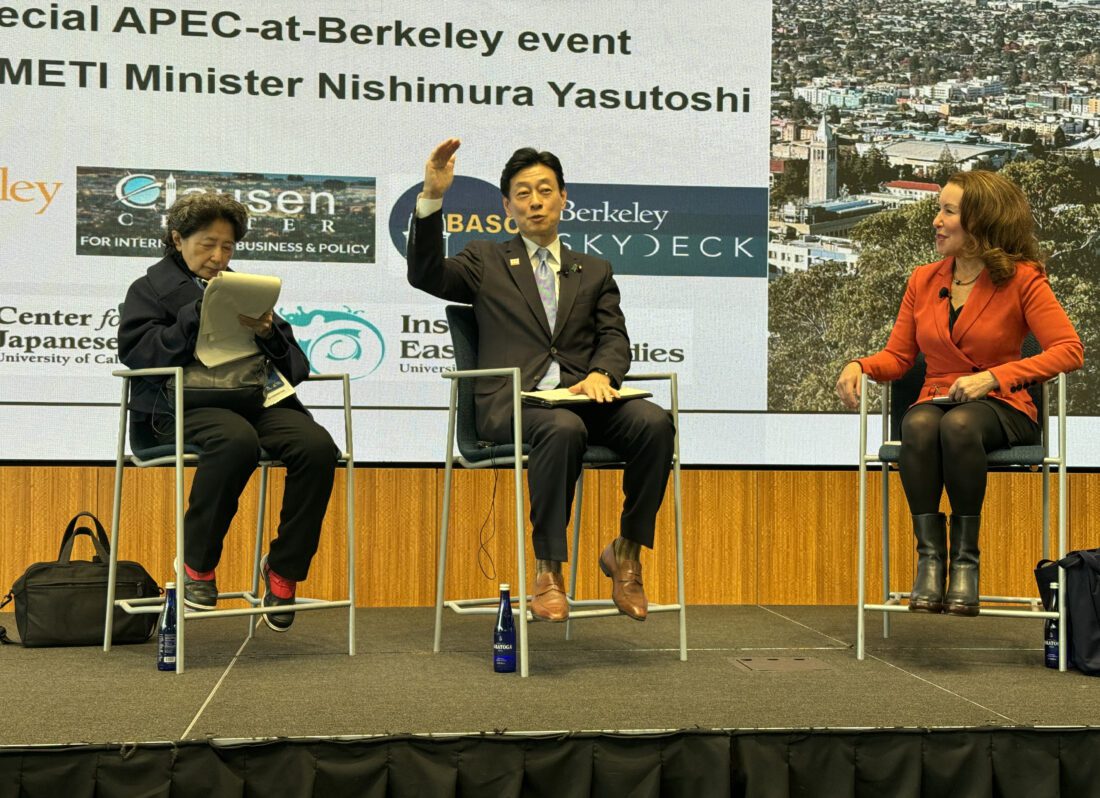

Nishimura Yasutoshi, Japan’s Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) visited UC Berkeley and the Haas School of Business this week to spread the message that Japan is making significant investments to transform its economy through entrepreneurship and innovation.

While Japan may be best known for its big companies like Toyota and Sony, “They began as startups first of all,” said Minister Nishimura, speaking through an interpreter in a conversation with Haas Acting Dean Jennifer Chatman. “Entrepreneurship is really in the DNA of the Japanese people.”

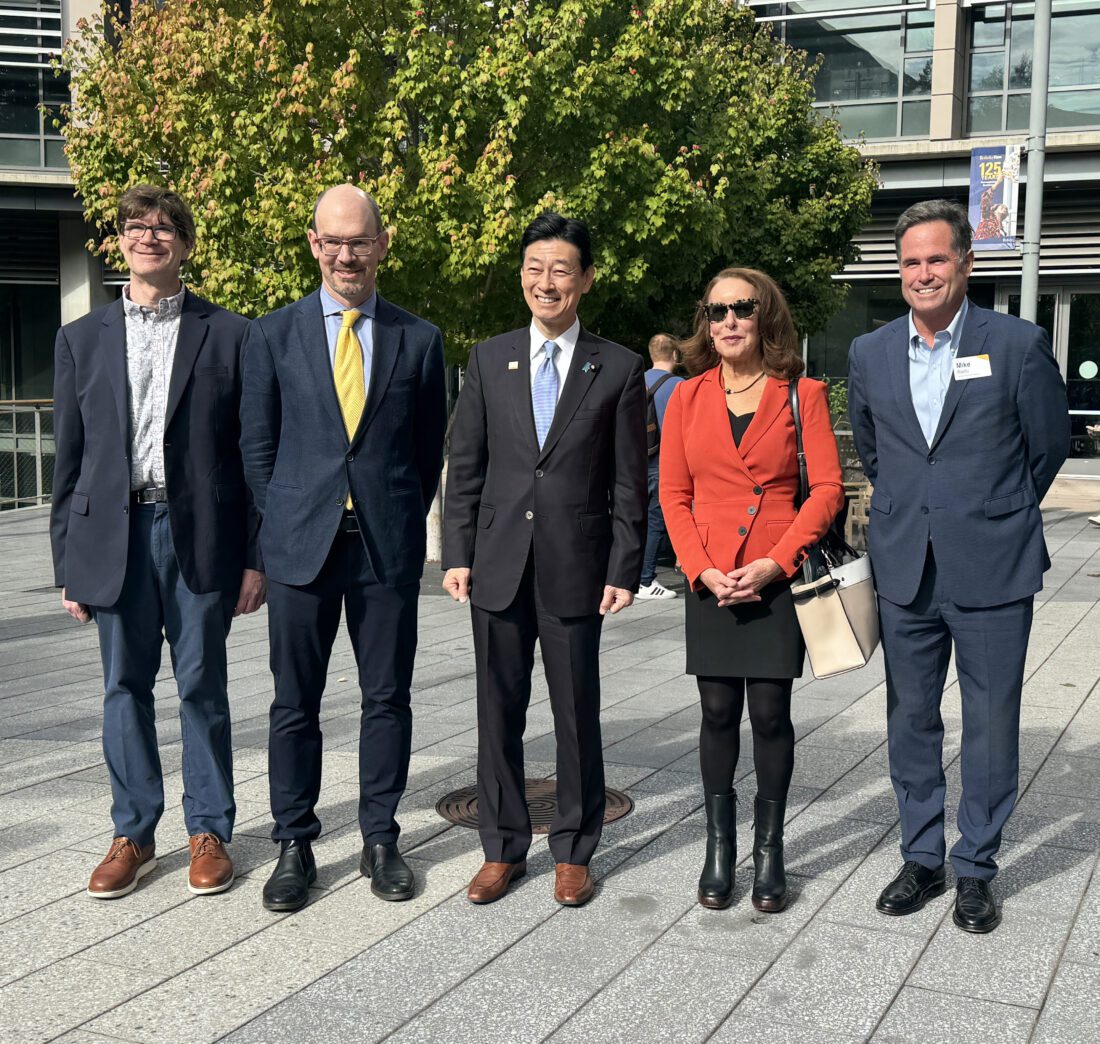

Invited to campus by the Clausen Center for International Business and Policy as part of events surrounding the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in San Francisco, Minister Nishimura’s visit also expanded the collaboration between UC-Berkeley and the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO). During the event, Caroline Winnett, Executive Director of the Berkeley SkyDeck accelerator, signed a memorandum of understanding with JETRO to further advance entrepreneurship, innovation, and scholarship.

Minister Nishimura also toured SkyDeck, which to date has hosted about 60 Japanese startups through its JETRO partnership.

Berkeley SkyDeck was thrilled to host Yasutoshi Nishimura, the Japanese Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry, for a visit to SkyDeck, following an MOU signing with @JETRO_InvestJP to launch our second international program. Learn more here: https://t.co/5SXLsxzXfy https://t.co/coKXsjQwyA

— Berkeley SkyDeck (@SkyDeck_Cal) November 17, 2023

In addition to the SkyDeck collaboration commemorated at Minister Nishimura’s talk, Berkeley Haas has a long tradition of partnering with Japanese companies and universities to promote innovation and entrepreneurship. In the past year, the Berkeley Haas Entrepreneurship Program has worked with Tohoku University to train top startups from the Sendai region in Lean Launch methodology. Haas has also hosted leading Japanese companies at the Berkeley Innovation Forum to explore building their innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystems.

To achieve its goal of a tenfold increase in the number of startups over the next five years, the Japanese government plans to send 1,000 entrepreneurs to the Bay Area over a five year span, and to invest in university partnerships, noted Haas Continuing Lecturer Jon Metzler, who helped organize the METI visit to Haas.

“The government of Japan is taking a number of measures to stimulate entrepreneurship, increase new venture formation, and nurture entrepreneurs with a more global mindset—including sending promising entrepreneurs to acceleration programs like Berkeley SkyDeck,” Metzler said.

‘Unicorns and decacorns’

After an introduction by Associate Professor Matilde Bombardini of the Clausen Center, Minister Nishimura delivered prepared remarks and sat for Q&A with Acting Dean Chatman. He said everyone who has visited Japan in the past few years is surprised by how much it has changed.

“In terms of macroeconomy, over the past 30 years because of deflation, it has been a challenging time for Japan. But now we are in an era when big changes are about to take place,” Nishimura said. Within the population of about 125 million, many entrepreneurs have been content to find success within the country. But Nishimura is encouraging young entrepreneurs to think big and “go global.”

“We are looking toward the emergence of many unicorns and decacorns,” he said.

Nishimura also talked about plans to build a next-generation semiconductor fabrication facility in Hokkaido, which will adopt a 2 nm fabrication process—a major technological leap compared to current fabs in Japan.

In addition to the Haas’ Clausen Center for International Business and Policy, the event was hosted in partnership with the Berkeley APEC Study Center, the Institute for East Asian Studies, the Center for Japanese Studies, and Berkeley SkyDeck, with support from the Haas Asia Business Club. The Japan Society of Northern California also helped promote the event.

How Berkeley Haas research fueled a company that could save Medicare patients from costly mistakes

Choosing a Medicare plan is both complicated and consequential. Berkeley Haas research has fueled a new company that simplifies the process, promising to save money and improve health for millions of people.

It’s Medicare open enrollment season, and the tens of millions of retirees who rely on the government program for health care are grappling with an abundance of options, a dearth of information, and no good way to personalize or compare plans.

“It is not a well-functioning market,” says Jon Kolstad, an associate professor at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business who studies the economics of health care. “And yet the choices people make have high financial stakes—consumers are typically on fixed incomes—and critical health implications.”

Kolstad has been studying this challenge since he was in graduate school and, with several academic collaborators, recently helped turn a broad foundation of research into a company centered on helping people make better decisions when choosing a Medicare plan. Healthpilot, which launched in late 2020, uses machine learning to compare Medicare plans and suggest options that are personalized to each person’s current circumstances, projected health needs, and risk tolerance. It’s also free to use.

“We recognized the power of this highly predictive algorithm developed to solve a critical unmet healthcare need for seniors who are evaluating Medicare plans,” says Healthpilot CEO Seth Teich. “We believe that Healthpilot’s platform is a transformative technology that empowers consumers to easily navigate through the complexity of plan choices to find, and enroll in, their best coverage option.”

A desperate need for innovation

People with questions about Medicare enrollment have long relied on phone calls to private agents who walk them through the decision. But there’s a problem: “In reality, these brokers, who are supposed to be experts, do no better at selecting a plan than the average person,” Kolstad says.

In a 2021 paper, Kolstad and several colleagues, including UC Berkeley economist Ben Handel, demonstrated that brokers are prone to the same flawed judgment as everyone else. For instance, they place too much weight on a plan’s premium while overlooking other costs, such as out-of-pocket expenses. The result is that consumers working with brokers pay $1,260 more per year on average than they would if they enrolled in the best plan.

This is not the result of brokers’ bad intentions but simply because solving which plan is best for which person “is a very complex computational problem,” Kolstad says. In fact, the 2021 paper found that when brokers were provided with an AI assistant to help them suggest a plan, they saved consumers about $300 per year. (This is a conservative estimate.)

Healthpilot’s promise lies with its ability to use AI to properly weight the many fixed and projected costs of every available plan, sifting carefully—and impartially—through these multidimensional relationships. The algorithm operates by comparing every Medicare enrollee with millions of similar people and then forecasting the likelihood of different medical complications. By pairing this forecast with known information—including, with users’ permission, secure access to the medications people take and the doctors they see, along with information they provide directly—Healthpilot then determines which plan is ideal and ranks the alternatives.

The algorithm also considers individual appetites for risk. “Some people have very little risk aversion, and they would rather have low payments now and gamble on how they fare,” Kolstad says. “The plan that gets recommended to this kind of person should be different than the plan that gets recommended to someone who is very risk averse, who wants a high premium now in order to know that they’ll be covered.”

Benefiting individuals and the marketplace at large

The financial benefits for individuals are straightforward: Choosing the right Medicare plan generally means better coverage and less expense. These savings also accrue to the federal government, which finances Medicare.

A subtler benefit are gains in well-being and even lower mortality rates. One working paper co-authored by Kolstad found that people who have to pay more out of pocket cut back on important health care services. A related paper, co-authored by Ziad Obermeyer of Berkeley Public Health with researchers at Stanford and Harvard, found that a $100 bump in per-month cost-sharing for drugs—exactly the kind of mistake people make without good guidance—increases mortality by 13.4%, as people forego essential drugs such as blood pressure medication.

Healthpilot is able to deliver these financial and health-related benefits to consumers for free because of the structure of the Medicare market. Since Medicare is a valuable source of revenue for insurance companies, the companies pay commissions to brokers for each person that they enroll. If Healthpilot sends someone to Humana, Humana pays; if instead the enrollee goes to Blue Cross-Blue Shield, then Blue Cross-Blue Shield pays.

That’s a crucial point: Because these commission amounts may vary by carrier, human agents may be biased in their plan recommendation based on the commission they are paid. Healthpilot’s algorithm does not factor commissions into its recommendations and does not steer people toward any particular plan or company based on financial incentives. “There’s no distortion in the platform or plan recommendation, which is unique in the industry,” Kolstad says.

This also has the potential to inspire greater innovation and efficiency in the insurance market as a whole—one of Kolstad’s main interests. As a point of comparison, consider the tech market: When a company like Apple creates a product that people like, they buy it; when it creates a product people don’t like, they don’t buy it. This is quickly reflected in the company’s revenue and share price.

Because insurance products are so much more complicated, consumer decisions rarely reflect clear notions about quality; people often enroll, and stay enrolled, in plans that don’t deliver value. Healthpilot, by sorting people into plans that genuinely benefit them, could bring much greater transparency into the marketplace and produce meaningful information for companies to build better plans, Kolstad says.

“For better or worse, we rely on competing private plans in Medicare. That’s the approach we’ve taken because we believe that a private market will offer innovation,” Kolstad says. “Giving customers a greater ability to match with plans that give them the coverage they want and need will reward innovators. That means Healthpilot isn’t just a digital enrollment solution for consumers but can be a tool to make the whole market function more as it should.”