Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist David Leonhardt believes that the American Dream has dimmed over time, but can rise again if the U.S. changes its policies.

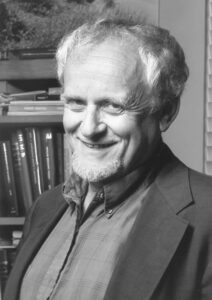

With nearly 25 years of experience reporting on economics for The New York Times, including serving as Washington bureau chief and starting the publication’s “The Upshot” section, Leonhardt spent years writing about the American economy. That formed the topic of his new book, Ours Was the Shining Future: The Story of the American Dream.

Leonhardt sat down with Richard Thaler, former president of the American Economic Association and the 2017 recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences,to discuss the history of the American economy and the drive behind Ours Was the Shining Future at a recent Dean’s Speaker Series talk, co-sponsored by the O’Donnell Center for Behavioral Economics.

Much of what he tells in the book is not a happy story. “The problem is…. that living standards have been really rising so slowly for many, many people at the same time that living standards at the very top are rising,” Leonhardt said. (Watch the video below)

The 1940s through the 1960s were times when society was geared politically and economically toward improving the living standards of most Americans, including those who didn’t have a college education—through labor unions and higher taxes for the rich to invest in public goods like roads and education, he said.

But “over the last 50 years, our society has really moved away from that,” he said, instead taking an individualistic approach that has not worked out for most Americans. “Part of what I worry about is that many of the ideas that we would come up with for helping lower-income workers to make a good living are basically versions of redistribution,” he said. “I don’t think that tends to be what people want.”

Describing unions as “grassroots foot soldiers” against a politically powered economy, Leonhardt contends that a strong labor movement is necessary to get us back to improving American society. He discussed the idea of developing new kinds of unions in the scope of current political and economic conditions.

While his book may not recount the happiest history, Leonhardt clarified that the future can still be bright. “I tried to emphasize ours was the shining future—and can be again,” he said.

Read the full transcript:

– Good afternoon. My name is Ulrike Malmendier, and I’m a professor here at the Haas School of Business, and I’m also the faculty director of the new O’Donnell Center of Behavioral Economics. And it’s my pleasure to welcome you here; it’s in the name of our dean, Ann Harrison. I’m truly delighted to introduce our two guests, David Leonhardt and Richard Thaler. Neither of them really needs an introduction. In fact, many of you New York Times readers have David’s flagship newsletter in the morning in your inbox every day. David has been at The New York Times for almost 25 years, since 1999, writing on business, economics for the magazine, opinion columnist in the spare time, founding “The Upshot” section, running the “Washington Bureau,” what did I forget? Oh, winning a Pulitzer Prize on the way. So, an amazing career as a journalist, and I’m fortunate enough to have crossed paths with him more than 20 years ago when he, with me just being fresh out of graduate school, took an interest in my own first behavioral economics research, which was on people signing up for gym memberships, paying steep monthly fees, and then rarely showing up at the gym. Discussing that research with David was not only really helpful for forming the research ideas; I also learned, from David, the power of storytelling, of using examples, personal experiences to convey a deeper concept. That’s something academic training tries to drill out of you, I have to admit. But now that I’m, for example, we just talked about it, involved in policy and convincing politicians to do the right thing, I am recognizing it as so powerful. So, all you future leaders here in the room, take note. David, also, while talking with him, actually gave us the title for our very first paper, I don’t know whether you remember. We’d called it something like “Time Inconsistency, Contract Design, and Health Club Attendance.” And then, David wrote a column, an economic column, which had the headline, “How much does it cost not to go to the gym?” And with his permission, we told the American Economic Review that we are renaming it into “Paying Not to Go to the Gym,” which was, of course, a much better title. We’re here today because David has just written his first book, “Ours Is the Shining Future.” It’s the story of the American Dream, which has been named one of the best books of the year by The Atlantic, The Financial Times, and The New Republic. The book starts from him telling the story of his own family, and then, examining the history of the American economy as it has evolved over the decades, examining the forces that have been driving the rising inequality and led to stagnation and lack of progress for many Americans. As we distill his argument, we see that David still thinks and argues that capitalism works better than any alternative we know of, but only a certain type of capitalism: one that’s softened by government intervention for the common good. And he urges us to recognize and foster the power of grassroots movements to instill humanity and opportunity for… Now, putting a more human face on economics is, of course, what our second guest, Richard Thaler is known for. And what won him the 2017 Nobel Prize in economic sciences. It is thanks to Richard that economics, which at times fell into the trap of pursuing analysis based on and enchanted by mathematical rigor more than driven by uncovering the truth about human behavior. It is thanks to him that we have learned again that we are a social science that deals with messy human behavior. And he has ushered these theories of behavioral economics into the mainstream with “Nudge,” his 2009 global bestseller he wrote with Cass Sunstein. I’ve known Richard even a few years longer than I’ve known David. Ever since here, at Berkeley Haas, I was fortunate enough to attend his behavioral economic summer camp in the big room down there, in the F building. Ever since then, he has been an invaluable source of inspiration and mentoring for me and for generations of behavioral economists. I view Richard as the true founder of our field, which includes, by the way, introducing us to Danny Kahneman, whom I also met for the first time at the very same famous behavioral economics summer camp, and who very sadly passed away last week. Kahneman was an academic giant, and introducing his and Amos Tversky’s work to economics was a game changer. In fact, in a time where a lot of psychology evidence in behavioral science is under fire for lack of robustness, as courageously exposed by our very own Haas colleague, Leif Nelson and his team. Richard had pointed us to rigorous psychology research, which we economists can build on, and which is here to last. So, I would like to add a really heartfelt thank you for those gifts to economic science, to a generation of behavioral economists, including myself. Like David, Richard is an amazing storyteller. Just Google “Beer on the Beach,” and you will see the type of narrative, which in my view is what he won the Nobel Prize for. So, we are in for quite a treat here, listening to their conversation right now. Just quickly, before we get going, you should all have note cards on your seat. If you have any questions that come to your mind, which would enrich our conversation afterward, write them down during the event and pass them on. My colleagues, Sarah and Carrie, will be collecting them. And then, the last 20 minutes, I will be able to ask a few of those questions to our two speakers. And with that, I now turn it over to David and Richard. Welcome.

– Thank you very much, Ulrike. And so, I’m going to steal a line from Malcolm Gladwell, who, when he and I did an event like this for I think my book “Misbehaving,” he began by saying how we had met in a hotel bar. And I’m going to say that David reminded me Sunday night, when we had dinner that he and I met in a hotel bedroom. And you know that, in Berkeley, that doesn’t raise as many eyebrows as it might otherwise. But the story is, and we just worked out that David and Ulrike met at the same American Economics Association meeting 20 years ago, 2004. David and I were supposed to talk about economics and have a coffee. And I said, “David, are you a sports fan?” And he said, “Yes.” And I said, “Why are we sitting here when we could be watching a football game?” And David, Sunday night remembered what the football game was, Titans-Ravens. So, since then, David and I have bonded over sports and many other things and have become great friends. So, here’s David’s book, and the title is “Ours Was the Shining Future,” note the tense there. So, why the past tense—and are we doomed?

– We are not doomed. Ulrike, thank you for that wonderful introduction. Thank you Richard, and thank you all for coming. Actually, first, this is from another era. I first learned about Haas when my first job in journalism was stuffing envelopes and opening envelopes for “Businessweek’s” business school survey.

– Oh!

– And so I would-

– Don’t get me started, I had that ruined business education.

– I was very low level—I was very low level. But I remember Haas students liking Haas when I opened those mini surveys. So the line, “Mine is the shining future,” is a line of an immigrant named Mary Anton who moved to the United States from Russia. And she has that line in her memoir. She’s looking up at the Boston Public Library and thinking about the antisemitism that she’s escaped in Russia and made it to the United States. And she describes, she says, “Mine is the shining future.” And, in the book that coins the phrase the “American Dream” in 1931, it ends by telling her story. And so, I knew when I was writing this book that I wouldn’t name it, I’m not good at naming things. My wife came up with the names for our children. I think Ulrike mentioned this.

– We about “The Upshot.”

– Yeah, so exactly, so, when we were starting “The Upshot” at The New York Times, I said to people, “There is no way I will come up with the name for this.” So I offered a bottle of champagne to whoever on the staff did, and someone did. And so, I let Random House and my agent come up with the name of it, and they did. Random House first suggested, “Ours Is the Shining Future.” And my agent thought that was a touch too optimistic. And so, she suggested “Ours Was the Shining Future.” And Random House loved the switch. I will confess that, though I love the title, it is, there is, I do think, “Ours Is the Shining Future” is too positive. But when I’ve gone around and talked about it, I tried to emphasize ours was the shining future and can be again. So we are not doomed.

– Yeah, yeah. Yeah, I don’t see that.

– No, it is, that is much of the argument of the conclusion. But yes. But look, much of the story I tell about the last 50 years is not a happy story. I mean, the first chart in the book is that, in 1980, the United States had a normal life expectancy for a rich country. Pretty similar to Western Europe and Canada. Little bit below average if you look, but right in the, kind of the heart of it. And starting in the early ’80s, we departed from the life expectancy line of every other rich country in the world. And for the last 15 years, the United States has had the lowest life expectancy of any country in the world. And it’s not particularly close anymore. And it’s driven overwhelmingly by trends among working-class people. And that’s not a happy story.

– No, and you have another chart showing a type of inequality that doesn’t get as much attention, which is, there’s a difference between rich and poor in terms of life expectancy. That’s quite sharp.

– Yeah, when you look at life expectancy for college graduates, the line actually looks pretty similar to lines for other countries. Whereas, and when you look at life expectancy for working-class Americans, even before COVID, for much of the decade before COVID, had almost completely stagnated. And people often say, “Well, is it X?” And the answer is yes and no. Is it guns? Yes. Is it opioids? Yes. Is it COVID? Yes. Is it car accidents? Yes. But it’s not any one of those things. It’s the combination of working-class life in the United States, that is Anne Case and Angus Deaton, that they’re known for “Deaths of Despair,” but their research is actually broader than that, and kind of looks at just how much, by many measures, life for Americans without a four-year college degree has really stagnated.

– So, the inequality has been a popular topic in economic circles, especially in recent years. Sort of two themes, one that I’ll call the French theme of Piketty and Berkeley’s own Saez and Zucman stresses the rise of the 1% or the 10th of 1%. So, all the billionaires, and then we’ll call it the “Chetty theme,” Raj Chetty and his army of researchers that are stressing the difficulty of, say, going from the bottom quintile to the second quintile. Your book is more about the latter, right?

– Yes.

– And so, what’s your take on, what you’ve learned about that and why is it that it’s harder than it was when I was a kid, or when you were a kid, for the people at the bottom to move up?

– I think I do focus more on what you’re calling the “Chetty” part of the story. But I also think the French part of the story is important. And a lot of the data that I use in the book comes from Saez and Zucman and Piketty. I think that the, what’s going on with mobility and opportunity for the bottom half is more important in part just ’cause the bottom half has many more people in it than the top 0.01%.

– Right.

– Right? And so, it just affects many more people’s lives. And I think if we had a society where, and we briefly had this in the late ’90s, if we had a society where the rich were getting a lot richer and inequality was rising, but living standards for most people were also rising, I think Americans would be mostly OK with that. I think the problem is the combination: that living standards have been really rising so slowly for many, many people at the same time that living standards at the very top are rising. And I do think there’s a relationship between that. I mean, I think the very, very rich have more control over our political process as a result of that. But I don’t think that’s the dominant explanation. I mean, what I try to argue is that as a society, we had a society in the ’40s and the ’50s and the ’60s for all of the terrible problems. We had a society that was very much geared politically and economically toward improving the living standards of most Americans, including Americans who didn’t have a college education. And that took the form of labor unions, which I know we’re going to talk about. It took the form of a political system that taxed rich people quite highly, that invested lots of money in things like roads and colleges. The University of California system came out of those years, and there really was an enormous emphasis to use the resources of our society to improve most people’s lives. There was also, and this is relevant for a business school, there was a culture in corporate America that seemed more invested in this country and in communities and that was a little bit less self-seeking. And I talk about some of the executives like that in the book. And I think, over the last 50 years, our society has really moved away from that, and imagined that a kind of laissez-faire individualistic approach could work well for everybody. Which I don’t think was a crazy theory, I just don’t think it’s worked out.

– So, there are, you sent me an email recently saying, “I know there are three things you’re going to disagree with me about, unions, immigration, and trade with China.” And so, we’ll talk about those because they’ll be interesting conversations. But so, you think Trump basically had it right?

– I do not think Trump had it right.

– OK, so-

– I would hope I have a long record of journalism that justifies that statement.

– Oh, OK. So, alright. So that was a joke, of course.

– Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

– So let’s start with unions. You tell several stories, including the workers in the Pullman train cars of how unions helped pull the bottom end up, so elaborate a little on that and what you think the, what the benefits are, and why is it that they have decreased in power and influence?

– Let me just start by saying, I’m aware that unions are flawed institutions. I’ve been in a union.

– So, noted.

– I’ve been in a union at The New York Times, if you asked me to list, I don’t have much of a temper. If you asked me to list the five times I’ve been silently angriest in my life, one of them would be when I went to my union representative at The New York Times to explain that my infant child needed neurosurgery, and there were no neurosurgeons in the union-covered plan. And I kid you not, my union representative said to me, “Have you considered calling a neurologist and asking if they also do surgery?” And you know, this most vulnerable moment of my life, I don’t know whether it was a bad attempt at a joke or a serious bad suggestion, but this was someone who at that point had power over me. Right? And was in many ways a monopoly. ‘Cause this was my health insurance plan. So I understand the way that people can be frustrated with unions, and I’m now a manager at The New York Times, and sometimes, the union stands in the way of change that I think is important. So I get that unions are flawed. I think the issue is that corporations are flawed as well. And when you have flawed corporations that are not checked by flawed unions, you have a really high inequality economy. And so, what I try to tell in the book is, if you look at the economy of the United States in the late-19th century and 19 aughts and teens and twenties, we had a tremendously high inequality economy without labor unions. And then, we had the enormous growth of labor unions, and we had this incredible rise in pay for working class people. And then labor unions started shrinking. And the time series works out almost perfectly that it is also the case that inequality starts rising. And it’s not, this isn’t simply time series evidence. There’s research by Henry Farber and Ilyana Kuziemko and Suresh Naidu and others that really look at similar workers and see that a unionized worker tends to make about 10% to 20% more than an otherwise similar worker. It doesn’t tend to come out of economic growth in most cases. It comes out of corporate profits and executive pay. It is redistribution, which I understand why many executives and investors may not like that, but I think it’s better for most people. I think without unions, corporations just tend to have too much of a power advantage in the negotiation. If I’m the boss and you’re the worker and I underpay you, it’s really hard for you to quit, right? ‘Cause you have a family. And so, I just think, I understand unions have flaws. I understand why they can drive people totally nuts, but I think we now have more than a century of evidence that when you have an economy without unions, many, many people end up earning relatively low salaries. And it’s very problematic

– So I mean, one question to ask is, “Is there another way?” So I have my own, I’m organizing a conference, a couple months back in Chicago. And because of some union rule, you know what a poster session is? Have you ever-

– Yes.

– Yeah, so, the poster sessions are at academic conferences. Typically grad students and junior faculty who can’t get on the program are given an opportunity to stand in front of a board where they’ve posted up some slides and talk about their research. It turns out, because of some union rule, it costs like $1,000 per board to put up. And so, we can’t have a poster session, which is damaging to the young scholars who, as Ulrike knows, I am always on their side. So, that’s a trivial version that we could tell thousands of these stories. Is there a way of giving power to the people without having the work rules that make organizations less efficient?

– I’ll half answer and then I’ll ask you a question. Most of the time that Richard and I have spent together, it’s me asking the questions.

– Yeah.

– So I can’t help myself. There’s another recent paper by actually some of the same researchers whose names I just mentioned, in which they look at workers relative preference between what they call redistribution and predistribution or market wages and post-government benefit wages. And basically, what they find, and I’m slightly overgeneralizing, but not by much here, is that everyone wants higher market wages for themselves. I think because of ideas involving dignity and respect. So, what rich people want, rich, particularly rich progressives, is they want a system where they make a lot of money; and then, they get to redistribute it through taxes and benefits. And what poor people and working class people want is a system where not, where they’re getting money through government benefits, but where they actually, their market wages are higher. And so, part of what I worry about is that many of the ideas that we would come up with for helping lower-income workers make good livings are basically versions of redistribution. Where New York Times journalists and MBAs and tenured professors get to make more money. And then we get to-

– Yay.

– Yay, we get to give it to people through taxes. And so, I don’t think that tends to be what people want. I don’t think it’s as healthy in a whole bunch of ways. So I guess my question to someone who is more skeptical of unions would be, “Do you think I’m wrong to be so negative about the economic trends for less advantaged people over this era when unions have been shrinking? And do you see some other way that we can have mass prosperity without a meaningful labor movement?”

– Well, I’ll respond by asking my next question as a way of answering that, which is many people admire the economies in Scandinavia, like, Denmark and Sweden, maybe even Germany. But we’ll let Ulrike opine on that if she wants. So people in Copenhagen seem to have good lives and are happy, but the distribution of income is much less skewed. So is there a way of achieving that? If I could plunk you and your family and social network into Copenhagen or Stockholm, do you think you’d be happier? And would that be a better model?

– Well, I think it’s, I mean, much of Western Europe does have stronger unions than the United States does, right? With both the advantages and disadvantages. So, it’s not simply a case of them having a larger, or a government system in which they redistribute income that way.

– Well, they have higher taxes and social network.

– Yeah.

– A social safety net as well. So unions are a part, I agree.

– Unions are a part of it. And I think, and look, I think unions are important both because of, I don’t think unions are the full answer to be clear, but I think it’s really hard to imagine us having an economy that delivers prosperity to more people without stronger unions, both because of what they get directly for workers in negotiations. Look, I was just, I’ve said a couple critical things about the union at The New York Times. The union at The New York Times just won pretty significant wage increases for its members. I am confident, as much as I like the people who run The New York Times, that they wouldn’t have given them that size of wage increase without the union having the threat of a strike. And I would say the same thing about GM and Ford. And so, not only do I think unions bring direct benefits to workers, but I also think they end up often serving as kind of grassroots foot soldiers in a society and an economy where more people have political power. So you mentioned Pullman, one of the heroes of my book is A. Philip Randolph. I think many people think of A. Philip Randolph, if they think of him today as a civil rights leader. And he was a civil rights leader. He’s the original organizer of the March on Washington. It’s a story I tell in the book. It was originally planned for 1941. He faced down FDR over integrating wartime factories. So he canceled the March on Washington in 1941. That’s what it was called, the March on Washington. And they rescheduled it 22 years later. And A. Philip Randolph was the first speaker at it. He was the elder statesman at that point. And it’s not a coincidence that the labor union that A. Philip Randolph built with these low-wage women and men who worked on Pullman trains basically became the seeds of the civil rights movement. That is often the way that these movements happen. And so, I think that labor unions are really important in multiple ways. I don’t think we should try to recreate the unions of the past. I think we need new kinds of unions. And I also think that for all their excesses, there are often ways for corporations to push back against those excesses. So the union at The New York Times not only has asked for higher wages, but it’s asked for a bunch of other things that the management said “no” to, right? And so, sometimes, what unions ask for don’t have to become policy.

– Yeah, I’m sure, the fact that The New York Times is mostly digital now is bad for the union.

– Yeah.

– Since there were lots of jobs making a paper.

– Yeah. And just to say, I don’t mean this to say it means that I’m right about this. I say it more as a piece of self-criticism. The process of working on this book made me think that, during my 20 plus years as an economics reporter, I hadn’t written enough about the importance of labor unions. So maybe that version of that old version of me was right. And you’re right. I think it’s a really hard and important question.

– Yeah, look, I’m asking the questions, so I’m not answering them. So, for once in 20 years, we get to switch roles. So, OK. Along with unions, the other second evil menace in your book are immigrants. Of course, we are the children of immigrants, and probably 90% of the people in this room are as well or are actual immigrants like Ulrike. So, of course, you’re pro-immigration, but you have some thoughts about immigration. You know, there are low- and high-skill immigrants, and I think California represents the value both provide. I mean, Silicon Valley would not exist if it were not for thousands of immigrant engineers and tech startup founders and so forth. And the rest of the state couldn’t exist. If you go anywhere where there are people working, they’re speaking Spanish. So it’s a state that doesn’t exist without immigrants.

– Yeah.

– And it’s the most prosperous state in the country. And it would be a prosperous country if it were a separate country. So, since you’re not anti-immigrant, what are the tweaks you would prefer?

– No, and I do have more criticisms of the way our immigration system works than many people with whom I agree on many other things. So, I think California’s an interesting case. I’m mostly not going to talk about California, but it’s, right, it is a very prosperous economy. It’s also a very unequal economy, right? Where all kinds of things like, homelessness and poverty, right? So it’s not a perfect economy by any means. Not that you were suggesting it was. So, I think, I have two basic criticisms in my book of the dominant political tribes in the United States. So far we’ve been talking about my criticisms of conservatives. And it’s not just conservatives, it’s many economists, right?

– Yeah.

– Yeah.

– Chicago school.

– Chicago school economists.

– They’re the other villain in this.

– And as I said, I think some of the arguments that people made in the 1970s about how to fix the American economy, ’cause it had real problems, were legitimate arguments. But I also think they made a set of predictions about what would happen if we had a lower tax, less regulation, less unionized economy where corporations were allowed to grow really large. They made specific predictions about how this won’t just be good for affluent people, it’ll be good for everybody. And I think those predictions have not come to pass. And so, part of what I’m saying is, “Let’s look at that economic system and be honest about what it is delivered for most Americans.” My second set of criticism is that I think, in the United States, as in parts of Europe and other countries, the center left party in our country, the Democratic Party has really moved away from the views and values of working-class people and often actually become disdainful of those views.

– You call ’em the Brahmin Left.

– The Brahmin Left, which is a Piketty line that I give him credit for. And I think it’s a great line. And look, this is where I, and I’m guessing many of you, spend my life, right? Like, highly educated coastal suburbs. And part of the reason I focus so much on immigration is that I think it’s actually a signature example of how relatively privileged progressive Americans have moved away from the views and the values and even the interests of less privileged Americans. And so, the main story I tell in the book is the story of the 1965 immigration law. And it’s really important to go back and look at that law and the people who are advocating for it: LBJ, Ted Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, a lot of moderate Republicans back when they existed. And what they said was, they said, “We’re getting rid of our old racist system of immigration.” They didn’t use the word racist, but that’s what they meant. Where basically all slots were reserved for Western Europe, and we’re replacing it with a system in which it will be first come, first serve. They specifically promised, specifically, repeatedly, that it would not lead to a large increase in the volume of immigration. This is one of the things that I actually found most enjoyable from a kind of academic process of reading this old work at the Library of Congress. Again and again, Ted Kennedy and LBJ’s cabinet secretary said, “Don’t you worry, we’re not increasing the amount of immigration, we promise we’re not increasing the amount of blue collar immigration.” The example RFK used is, he said, “We are not bringing more ditch diggers to this country.” Because they understood that most Americans were not in favor of a massive increase in immigration. They were completely wrong about what their own law would do. I don’t think they lied, I just don’t think they thought about it very carefully. And the fact is, we have had an enormous increase in immigration. And so, now what happens is that many people on the left and the pro-business right as well, they say, “Well, that’s OK because immigration has no costs for anyone. It is a free lunch, it is great for the immigrants, and it doesn’t have any wage costs for anyone else.” And I think most Americans look at that, and they don’t believe it. And I think we can dig into the data about whether immigration has costs or not. I think it has some costs for lower-wage workers, and I think many people fundamentally understand this. Why did doctors make it so hard for immigrant doctors to come into this country and compete with them? Well, if immigration didn’t actually have any wage costs.

– You mean the MD cartel you’re referring to? Yes, yeah.

– Yes, the MD cartel says, “You can’t be a doctor in this country unless you’ve done your residency here.” That’s a ludicrous rule, right? If you… Because we’re saying that you can’t get good medical training in India or Australia or Britain. Sure, seems like you should be able to. And, but doctors understand, right? That having a lot of people come in and compete probably creates wage pressure for them. And so, I tell the story of immigration because I don’t think Americans, including many recent immigrants who were uncomfortable with really high levels of immigration, with an immigration system that doesn’t work, with high levels of illegal immigration. I don’t think they’re bad people. I don’t think they’re racists. Some of them are, but I don’t think it’s inherently racist to be skeptical of immigration. And we’ve ended up with a situation in which our left of center party, particularly elites in it, look at those people and say, “No, no, no, no, no. You are wrong to have those views. You’re ignorant. You are hateful. You need to understand that more immigration is better for everyone including you.” And I think that’s really debatable. And I also think that a lot of Americans look at that party and say, “No thanks, you’re disdainful of me.”

– OK, I think, I’m going to give you a pass on China and free trade in order to get you into trouble on something else. You had a piece recently on the SAT.

– I did.

– And there are basically three policies that are around. One is the old policy that you had to submit test scores if you wanted to get accepted to an elite college or university. Dartmouth, among others, has recently instituted that. Then there are the second policy that University of Chicago and many others have, which is it’s test optional. And then, University of California, where you’re forbidden from disclosing your SAT score. I don’t know whether you can whisper it in an interview, you guys might know, put it, tattoo it but so give us your brief take on why you think the old system there is the right one.

– So if we were trying to fill an orchestra and we discovered some kind of test that helped us predict how good a violin player you would be, would we dismiss that test? If we were trying to fill a basketball team, I am a huge basketball fan. It’s possible, I was at a dinner last night where I was sneaking looks at Caitlin Clark versus Angel Reese on the side of the dinner. If we had a basketball team and there was a test we could give the players that would tell us how good they would be at shooting, would we want to look at that test in order to decide who should play on our basketball team? Of course we would. And we wouldn’t spend any time agonizing over it. For years, the research showed that the best way to understand how good a student someone would be was to combine their high school grades and their SAT, that both were better than one alone. Over time, that is still the case, but over time, it has become clear: the SAT is better than grades in part because of high school grade inflation. Berkeley cannot fill its college ranks with everybody who gets A’s, you don’t have room for everybody who still gets A’s. And so, even though that is the case, many colleges have decided that they are not willing to either. You don’t have to submit scores, or, as the University of California does, they will not accept scores. It is also the case that when you poll Americans, more than 75% of Americans, including more than 75% of every major racial group, Black, Latino, Asian, and white, say that college test score, that standardized test scores, should play a role in college admissions. And so, this to me, it’s not quite as important as immigration, but this to me is another example in which the Brahmin Left has gotten on the other side of what I think the empirical evidence shows; and that, if we want a world where we are admitting the students who are likely to do best in college, the SAT and ACT help us discover that. And yes, they have class gaps. Yes, they have racial gaps because we live in a deeply unequal society in which everything has class and racial gaps. But, and this is a point that Raj Chetty makes, the class and racial gaps on the SAT are nearly identical to the class and the racial gaps on the NAEP. Now, I’m guessing many of you don’t even know what the NAEP is. The NAEP isn’t just a low-stakes test; it is a no-stakes test. It is a test that third and eighth graders take that has no bearing on the student’s future. It doesn’t even determine whether you get into honors algebra. It does determine how schools are graded, right? So, when you hear the nation’s report card, and you hear which states are doing better, that’s all the NAEP. But it doesn’t matter for students. So, no one ever takes NAEP test prep. People don’t go to Stanley Kaplan for the NAEP because it has no impact on their lives. The racial and class gaps on NAEP scores are nearly identical to the racial and class gaps on SAT scores. And so, yes, the SAT is picking up inequality, but if colleges use it right, they can actually use it to identify lower-income kids and underrepresented minorities who are going to thrive there. And I kind of don’t understand the idea that there is this useful, important information that we’re scared of looking at.

– Well, I agree with you. And let’s turn it over to Ulrike and the audience.

– Excellent, well, thanks so much for a really fascinating discussion. Particularly your discussion about unions striking a court, so lots of questions about that. To comment briefly on the German unions, they make my life very hard right now when I have to fly to Berlin and I land in Frankfurt and my Lufthansa flight doesn’t go because they are on strike. I tried to take a train. Well, it turns out the train is also on strike, and I’m stuck in some airport hotel. So the unions, for that reason; and because my Italian husband is smiling about the trains in Italy going smoothly and everything working, and in Germany, everything breaking down. So that is a problem. But more seriously, the kind of two issues. One is, in some sense, “What are the union negotiations driven by?” You had this heartbreaking example of your personal case where the person clearly wasn’t trying to maximize your welfare, quite to the opposite, at least in Germany, the discussion is right now about career concerns of people who want to be elected to be a union leader and might exaggerate in their demands for populism reasons, basically. So in terms of the design, I think there’s a lot to be done. There’s also the question, and that’s the traditional old question about unions. That they are an instrument to help the people who are in the “in-group” to get higher wages. What about the people who don’t have a job, right? Might they be harming them if the outlandish demands of The New York Times union had to be agreed upon, which you said that they weren’t in the end, would that mean, we might not have a New York Times anymore; or we have The New York Times because it would be so much? So this in-group, out-group question and the question, so, you in your book and in your discussion right now, we’re a lot focusing about unions and wages and how they’ve correlationally seem to have helped the lower deciles and quintiles. I would love for you, and one question goes in that direction to bring it together with the loss of manufacturing jobs or generally industry restructuring and certain jobs and companies from the traditional mining to much broader jobs disappearing. So if that’s our concern, that people don’t have a job at all anymore, hence no income, if it’s not about how low it is and rising it, but just allowing people to make a livable income and have prosperity across all regions of the U.S., how do you see the way forward here? And actually, maybe we can bridge it a little bit to behavioral economics in a second; and well, I’m happy to step in, but hear your thoughts about that. Do you see, is it contrast there, as maybe the unions being a positive force on the wage increases, conditional on being, having a job, but possibly to the detriment of those who are outside?

– So, I’ve been now going around to many campuses talking about my book, and one of the things, a question I occasionally get is, “You talk about all these problems of capitalism, but you treat them as manageable. Maybe capitalism itself is the problem, and we should instead just reject capitalism.” And I say, “The problem with that idea is that there has never been a noncapitalist society that has delivered really good living standards for large numbers of people.” Like none, right? And this is a somewhat indirect way in answering this, I’m sorry, Ulrike, but I actually feel this comes from the other political side, but I actually feel somewhat similar about unions, which is for all the problems with unions, I really struggle to find an economy that has delivered mass prosperity to huge numbers of people without a really important labor union presence. And so, while I agree with many of the problems with unions and think they need to be checked and think that public sector unions can be particularly problematic because they’re not always ways to check them, I would actually be quite happy if we could find some example of a society and an economy that delivered mass prosperity and had really healthy wages for people who are less fortunate than I am that didn’t have unions. ‘Cause I see all their problems, but I really struggle to find such an example and the examples where capitalism, where living standards tend to be best to me are almost always capitalist economies where you have a pretty meaningful government and labor presence. And to the second part of your question about jobs, I do think that unions can sometimes sacrifice jobs for the sake of wages. I think, in the United States today, we don’t really have a jobs problem. We have a good jobs problem. And so, if some of the tradeoff is that we’re going to end up eliminating some lower-paying work and creating some more good-paying work, that’s a trade off I’d be willing to take.

– Yeah, so let’s actually, let’s continue on that, and let’s leave the poor unions just for a second out of here, even though there’s so many questions about them. But will that happen? Why is it not yet happening? So I’m asking myself that question if I look at U.S. data, I am asking myself that question tenfold when I look at German data or any other population, which is much more dramatically shrinking, partly because they’re even less of an immigrant country than the U.S. We have this huge lack of hours worked to increase productivity, and yet, I don’t see wages for lower-level jobs and training of people who land in lower-level jobs and efforts put into making sure that they get an education, so that they don’t land in these lower-level jobs, increasing as much as it would be good for aggregate productivity. That could be a way out of this problem you guys were discussing about, “How do we get people not just to get money redistributed, but to earn a higher wage. Why is that not happening?”

– I think it has a, I was just talking about the United States, not Germany. I think it has a huge amount to do with bargaining power, that it is still the case that it is very hard for workers to be able to negotiate for really good wages when they are each on their own, right? As opposed to being collectively together.

– Yeah. But I mean, even before they land on that job. So I am born into an area with not the best schools, and I’m going to get a training that won’t allow me to apply for some upward trajectory in terms of career. Politicians, as much as anybody who’s working in the economy and running a business, should say, “Well we should go in there, we should get here in the U.S., you have the no child left behind policy. You should really have no possible member of the workforce left behind a policy, to get them to a level of training and make the best out of their talents. I don’t see a dramatic change happening, which I would’ve predicted given the population changes.

– I do think the Biden administration deserves some real credit for their efforts in some of these areas.

– Bidenomics.

– But yes, I mean, the Biden administration really has tried very hard to invest in regions that have had less economic growth even though many of those regions are not blue areas. And even though Biden seems to be getting no credit for it politically, which is a real mystery, I mean, you look at a state like Ohio, where they’ve opened a whole bunch of semiconductor factories, it’s not going to turn around the economy immediately, but it really should, in the long term, make a meaningful difference. And I do actually think this is part of, to come back to our first question about why, despite the story I tell, it’s not that I am optimistic, it’s that maybe I’m hopeful. I do think we have the tools to do it. I do think policymakers have increasingly looked at the evidence, the economic evidence, and tried to change things. And I think the Biden administration has really tried to put in place some policies that are responsive to the fact that a whole bunch of market-based systems haven’t delivered what they promised, including some of these ideas. Now, it’s going to take a long time, and I told you, I don’t have an answer for why he’s getting no political credit for it.

– Yeah, so a little more is the shining future, a little more optimism.

– Could be.

– OK.

– Yeah.

– Now, one related question, which popped up in a lot of cards I got, is about the role of AI. So, how do you think AI will affect the income, living standards, distribution? How does it play into the theme of your book?

– Can I admit our conversation on the way over here?

– Yeah.

– We were driving over here, and I said to Richard, “I have to admit something that’s a little embarrassing, which is I don’t totally get why AI is going to be such a big deal.” It’s not that I doubt that it will be a big deal, but when I ask people for examples of how it’ll be a big deal, they’re all kind of like, fairytale, either we’re all going to die, or, and then when I go and use it, it’s kind of, eh, and you didn’t disagree with me.

– Yeah, I mean, look, neither of us are experts on AI, but my take on it is that, I don’t know enough to know whether I should be afraid, but I do know there’s enormous room for improvement on things like call centers.

– Yep.

– And you know, one example, my home wifi went out and OK, I call the cable company, God forbid, and they say, “Alright, reboot your router.” I did that. OK, oh, then we do thing two and she has to do that and that doesn’t work. And you know, this is taking half an hour. And then she says, “Oh, OK, now we have to do thing three,” and that works. A month later, the same problem happens: I get to some other person and of course, we have to go through thing one and thing two why doesn’t the system know this is the guy who called a month ago and what you do is press thing three and right? I mean, we all live through those horror stories all the time. It’s not, yes, it’s a virtual problem, but you know, it’s like, all, you know what I call sludge, there’s sludge everywhere and it seems like AI could improve that a lot and whether the world ends, I don’t think that the world will end in my lifetime or yours, maybe your kids.

– The two things that so-

– So, why do I worry?

– The two thing… The, the-

– Social preferences?

– I do actually think there’s an interesting relationship here to political power. We didn’t talk about antitrust, but I talk about antitrust a fair amount in the book. Robert Bork is another character figure in the book. He’s famous not for his antitrust work, but it’s the most important work he did. And even if you were right, and I’m sure you are, that AI could solve all those problems if the cable company basically has you captured, they have no interest in solving it, right? And so, we need to not only get the technology, right? But we also have to get some of the power dynamics right. And we have to make sure that we actually have-

– Yeah but Elon will supply my-

– He will get ’em.

– And then I’ll have no worries.

– I do think it’s the, David Autor of the MIT economist has gotten some attention, including a recent piece in The New York Times about how he actually thinks AI could reduce inequality by basically giving less skilled, lower-earning workers the power to be more productive. Right? And that’s a version of what you’re talking about with the call centers. So, if there was someone at the call center who actually had the ability to fix when my NFL RedZone package goes out-

– Oh God.

– At Sunday at 1:45 and my Texan wife is not happy about it, and I’m going totally nuts about it, and we’re all running around in our house, “How can we watch football?” And if we could call someone and basically have them fix it, that person could make more money, right? And so, I do see, theoretically, how AI could actually be inequality reducing, but in the short term, this wasn’t exactly your question, I would just really like it if some people could do a better job just giving us examples of here’s how AI can improve your life a little bit right now.

– Yeah, so, I mean, I think there are good example of how, in particular, natural language processing can help us to substitute certain jobs, including the ones that Richard mentioned. I do think it needs to come in combo with a renewed effort to invest in the human capital of the people who would’ve otherwise ended up in those jobs. And you are more optimistic on that than me, I have to admit. But you brought up another point, which is politics, political power. We also had a question about that, about the U.S. Congress being the lowest productivity Congress in history in terms of legislation passed, and how you can be standing here and saying, “Well, if you just get our act together and focus less on ego and narcissism and on the common good, things will get better because how will the framework be created to provide the guardrails for that in the current situation.”

– So the statistic on the lowest productive Congress was, I think it’s the current House, right? I do think, look, I have criticisms of the Biden administration. I think they’ve completely mishandled immigration along some of the lines that you would guess based on what I’ve said, right? I mean, if you go back and read the Democratic Party’s 2020 platform on immigration, it’s all about allowing more people in. It’s almost nothing about figuring out a way to prevent the kind of problems we’ve had. That is a radical change in the Democratic Party. Go back and look at the way Barack Obama talked about immigration; it’s very different. So, I think Joe Biden has mishandled immigration. I think he can fairly be blamed for a meaningful part of the problems at the border. So I have criticisms of the Biden administration; however, I think they’ve gotten a lot right. I mentioned the semiconductor policy. When Joe Biden took office and was talking about bipartisan legislation, a lot of people, including me, had a little bit of reaction of, “There he goes again,” like imagining a Senate that doesn’t exist anymore. And Joe Biden passed a really impressive group of bipartisan legislation. The semiconductor bill was bipartisan; the infrastructure bill was bipartisan. Some of the military stuff was bipartisan, and he didn’t let that keep him from passing the stuff that Republicans were never going to agree to at the same time that he was passing the bipartisan stuff, and I say this not critically, he jammed through a bunch of bills, like incredible fundings for clean energy research and making health care cheaper that Republicans were never, ever going to agree to. And so, I am not naive about the political challenges that face us. I am specifically worried about the threat of what a second Trump term would mean, given what he has said about his, how he views democracy and how he would use the political system and the justice system to go after his enemies. How he would round up huge numbers of immigrants. I mean, it’s really authoritarian, frightening stuff. And so, I’m aware of the risks and the challenges we face. I do nonetheless think there is evidence both over the last few years and in the 21st century, if you include marriage equality, if you include Obamacare, that our political system, when people organize, can actually be responsive to real problems in society.

– Isn’t that an optimistic word to end on? Thank you so much.

– Thank you.

– That was a fantastic conversation. Great questions. Thank you very much.