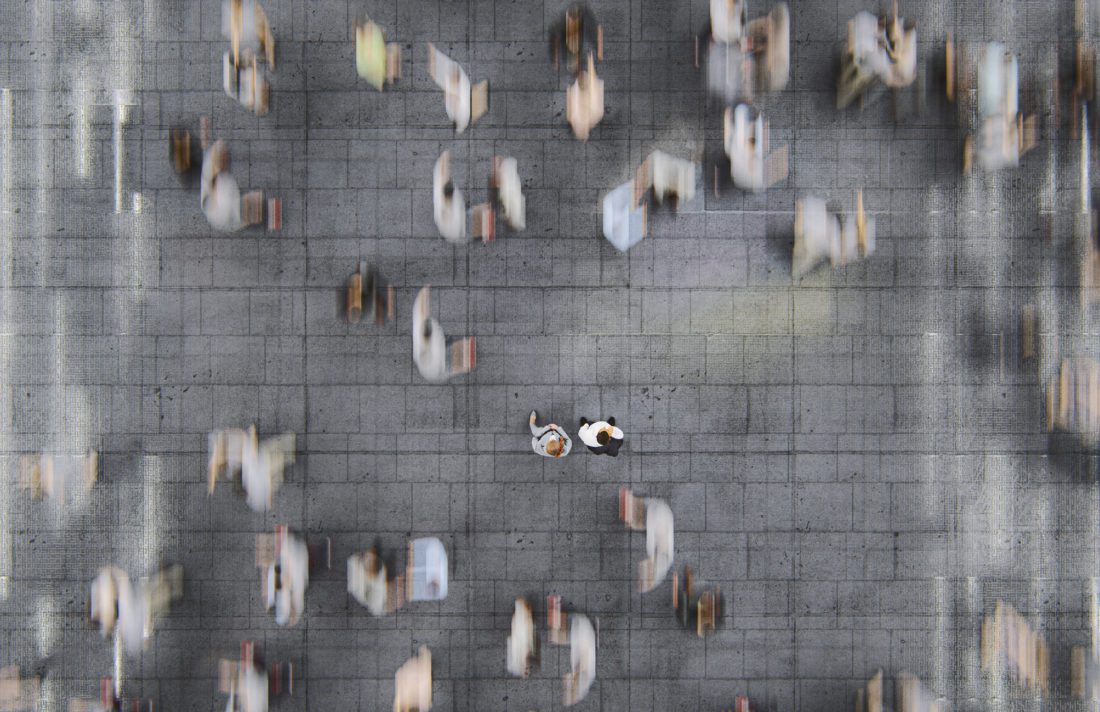

Former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy named loneliness as the most significant preventable disease in the country. And the pandemic-driven mental health crisis has underscored the consequences of social isolation.

Yet in everyday life, most of us make a habit of cutting off conversations with new acquaintance after a few minutes of polite chatter—whether it’s on an airplane, at a conference, or at a cocktail party.

This tendency to cut things short not only runs counter to our own best interests, but it’s based on fundamentally mistaken beliefs about conversation and relationships, according to a new study co-authored by Juliana Schroeder, a Berkeley Haas associate professor and Harold Furst Chair in Management Philosophy and Values. The study is forthcoming in The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

“All close friendships begin with a conversation between strangers,” said Schroeder. “The more you talk with someone, the more you know about them, and the more you potentially have to talk about.”

Yet that’s the exact opposite of people’s intuition: Most people are convinced that they will run out of things to say pretty quickly, so they end the conversation before it runs dry, the study found.

Strangers on a train

As a social psychologist, Schroeder has long studied the power of social connections—even of the most casual sort. In a 2014 study, she and co-author Nicholas Epley of Chicago Booth corralled commuters into striking up conversations with those seated near them on buses and trains. Despite telling the researchers they thought they’d be happier keeping to themselves, those who chatted with a stranger said they had a more enjoyable commute than those who were asked to stay disengaged or commute as normal. (In an effort to combat polarization and isolation, the BBC later implemented the idea on the London Tube, creating designated chat cars stocked with conversation-starter cards.)

This time, Schroeder and co-authors Ed O’Brian, an associate professor at Chicago Booth, and Michael Kardas, a post-doctoral fellow at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management, looked at how people feel during conversations with strangers, and why people disengage so quickly. In five experiments with about 1,000 participants matched with random conversation partners, they found that most people predicted that their chats would get less enjoyable over time. They did not—when the researchers measured people’s self-reported emotional experiences over the course of their conversations, they found that their enjoyment held steady, and for many people it increased over time.

“We found people mis-predicted the trajectory of the experience of conversation,” Schroeder said. “If you listen to the same song over and over again or do the same activity over and over again, your enjoyment might go down. But it’s not the same with conversation, which can go in so many different directions.”

Breadth over depth

In one experiment, people preferred to switch conversation partners each time they were given a chance, rather than sticking with one partner. But switching around didn’t increase their enjoyment, the researchers found.

“People seem to prioritize breadth over depth,” Schroeder said. “Instead of investing in the same person, they opt to switch—which to me means people are missing a fundamental feature of relationship building.”

Fear of having nothing to talk about

What was most surprising to Schroeder was her findings about why people cut things short. It wasn’t driven by awkwardness or other factors, but rather by people’s worries that they would run out of things to talk about, they found over multiple experiments.

In perhaps the most compelling experiment in the paper, participants were given the choice between sitting alone in silence—without their phones, internet, or other distractions—or chatting with another person for 30-minute session. Most chose to spend the better part of the session in silence. They reported less enjoyment than the pairs who were forced to keep talking for the full 30 minutes. In other words, those who were required to talk actually had a better experience than the people who freely chose how to spend their time.

“There are so many good reasons to be socially engaged for people’s physical and mental health,” said Schroeder. “Yet we find in many contexts that people tend to be less social than is optimal for their well-being.”

Exploring the psychology of why people choose to disconnect from others is an important area for future research, she said.

The study:

“Keep talking: (Mis)understanding the hedonic trajectory of conversation.”

By Michael Kardas, Juliana Schroeder, and Ed O’Brien

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (forthcoming – advance online publication 2021)