As a presidential candidate, Donald Trump accused Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos of buying The Washington Post three years earlier to benefit Amazon, and to gain a public forum to criticize Trump, as reported by CNN.

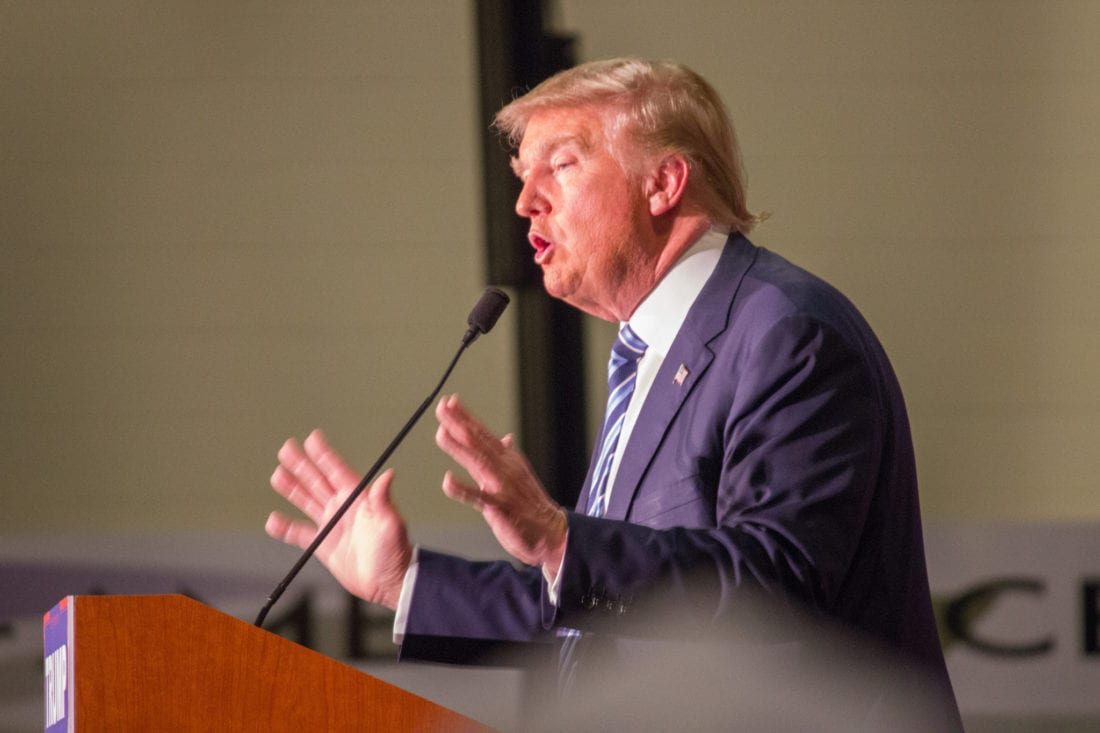

“And believe me, if I become president, oh do they have problems. They’re going to have such problems,” Trump threatened at a campaign rally.

Statements like those prompted economists at Berkeley and Georgetown to examine the probable approaches to antitrust enforcement under the new administration.

In “Whither Antitrust Enforcement in the Trump Administration?” published in The Antitrust Source (February 2017), Professor Carl Shapiro at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business and Steven Salop, a professor of economics and law at the Georgetown Law Center, voice concern about the potential abuse of presidential power in using antitrust to punish political enemies. They recommend that the president proactively enforce antitrust rules, following established principles, to maintain confidence in the market system.

Shapiro and Salop outline two courses of action that may frame the Trump administration’s antitrust policy: a “laissez-faire” or permissive approach and a “reining in corporate power” approach which would be more reflective of President Trump’s earlier campaign rhetoric. While they believe the president will lean toward less intervention, they acknowledge policy options could run the gamut from lax to populist.

“The question is where the new White House will draw the line between a laissez-faire approach and the populists’ cry for reining in corporate power,” says Shapiro.

A Marketplace poll prior to November’s presidential election found that 62 percent of Americans believe the economy is rigged to benefit the wealthy, politicians, banks—and corporations. President Trump campaigned on a platform to eliminate such corruption.

Antitrust laws are designed to protect consumers. Shapiro and Salop warn against using antitrust enforcement for broader purposes, such as favoring U.S. companies or domestic employment, and note that such an approach would require legislative changes.

“Our antitrust laws are not designed to consider broader objectives such as employment. They are concerned with preserving market competition to protect consumers,” says Shapiro. “A broad and vague ‘public interest’ standard is not what our antitrust laws call for, and moving in that direction would be hazardous.”

Shapiro served as the Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Economics at the U.S. Department of Justice, Antitrust Division, from 2009 to 2011 and from 1995 to 1996. More recently he also was a member of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers from 2011 to 2012.

The regulatory environment can be challenging for the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) antitrust enforcement officials who police merger proposals. Sector-specific regulators are often “friendly” with the industries they regulate or are “captured” by them.

“Often it’s unpopular with politicians and their contributors when the DOJ or FTC goes after a large American company, but the Obama administration showed a lot of feistiness in blocking mergers. Antitrust enforcement is a great strength that America has, which is continually tested by companies who seek political favor,” says Shapiro.

The article cites as an example the deal Trump made with Carrier, a division of United Technologies, to keep a furnace plant in Indiana. For the most part it was deemed an unusual approach for a president-elect. “The concern is that it was implemented by way of an ad hoc threat of retaliation rather than as part of a rule-based process,” Shapiro and Salop write.

As a result, Shapiro believes President Trump may be tempted to continue to cut deals with corporate CEOs going forward, rather than let the DOJ perform its law enforcement mission based on the facts and the law, without political influence.

Shapiro and Salop also suggest the use of “merger remedies” may help protect consumers while maintaining market confidence. For example, in 2015 the FTC allowed Dollar Tree to acquire Family Dollar stores if it first sold 330 stores in certain cities to preserve competition in those markets. “A merger remedy should be applied case by case after a detailed analysis,” says Shapiro. “The FTC has a lot of discretion in determining what is an acceptable divestiture.”

President Trump has yet to name the incoming antitrust leaders at the DOJ and the FTC, but Shapiro believes the future of corporate America—and a country divided between the wealthy one percent and the working class—will be affected by that leadership, according to Shapiro. He says if federal antitrust enforcement wanes, state attorney generals may be more compelled to step in.