Haas Voices is a first-person series that highlights the lived experiences of members of the Berkeley Haas community.

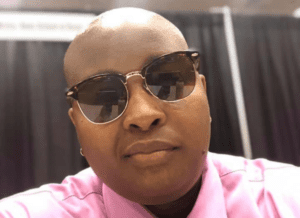

Born and raised in Chicago’s South Side, Verse Gabrielle is an associate director for the full-time MBA admissions program at Haas. Gabrielle, who uses “shey, sheir, shem,” pronouns that are preferred by some nonbinary and trans people, is also a poet, a playwright, a wife, and mom to four-year-old daughter Lyric Assata. In this Haas Voices interview, Gabrielle talks about growing up, being queer, and the healing power of intellectual curiosity and the spoken word.

I knew from as early as six years old that I was queer. But queerness was not celebrated in my family. I enjoyed having male friends and playing sports with boys my age, but I was never interested in the male gaze. I despised wearing dresses, playing with Barbie dolls, and never considered myself overly feminine, which was met with a lot of disdain.

When I was a freshman in high school, I told a family member that I liked girls. I was advised to keep the secret and not to disclose it to anyone. So I did. I suppressed my queerness until I deemed it safe to come out. Unfortunately, I was forced back into the closet until I turned 18.

Book smarts and intellectual curiosity are what saved me.

I graduated as valedictorian of my elementary school. Instead of attending my neighborhood high school, I went to De La Salle Institute-Lourdes Campus (DLS), one of the top private schools in Chicago. After completing my freshman year, I transferred into the honors program at DLS. I was ranked #6 in my class, graduating with a 4.667 G.P.A.

In my senior year of high school, I applied for and was awarded the Bill and Melinda Gates Scholarship. I felt like I had secured my financial future and could leave behind all the drama. I decided to go to the University of Minnesota, where for the first time in my life, I could be my authentic self. I started dating women, joined the LGBT student union. It was freeing.

While my intellect saved me, my spoken word helped heal me. I started writing poetry when I was about 10 years old, performing at talent shows and school assemblies, but it wasn’t until the summer before I went to college that I started performing at open mics in Chicago.

In college, I joined a student club called Voices Merging and later established the group Poetic Assassins. We’d travel and perform at different universities and colleges around the U.S. My poetry spans topics of internalized homophobia, racism, sexism, misogyny, the prison industrial complex, and gender roles.

Spoken word was my therapy: it helped me escape and process all the trauma I endured in Chicago. That’s where I let out all of the anger, rage, and pain. It also opened many doors for me. My poetry has been published in a few anthologies, including “When We Become Weavers: Queer Female Poets on the Midwestern Experience.” I’ve also written and collaborated on a spoken-word play, and facilitated poetry workshops focused on the intersectionality of race, class, and gender through a hood-feminist lens (i.e. Black feminist critique of traditional feminism).

I’ve been called dyke, bulldagger, male-woman, he-she, and chi chi man, which was hurled at me as I walked the streets of Kingston, Jamaica.

My artistry allowed me to move and operate in different spaces, but it didn’t shield me from bigotry, homophobia, and microaggressions on and off campus. I remember going to a rally almost every other weekend to protest against police brutality and crimes against Black and Brown people. I’d go to these protests to show solidarity because I am Black and I’m absorbing the pain like everyone else, but I’d also face homophobia from members of the Black community because my physical appearance and queerness didn’t fit the mold of what an “ideal Black woman” looks like. I’ve been called dyke, bulldagger, male-woman, he-she, and chi chi man (which was hurled at me as I walked the streets of Kingston, Jamaica).

Being queer and masculine-presenting has affected my relationship with straight men and women. I get weird looks and sometimes I’m questioned when I enter the female restroom, which is where I am most comfortable. I have had verbal altercations with men who’ve had issues with how I express my queerness being masculine-presenting. I’ve also had women express their discomfort with my presence in professional and communal spaces because they feared I was romantically interested in them.

I have many identities, however the core of my identity is my unapologetic Blackness: Black Buddhist, Black mother, Black queer, Black wife, Black woman, and so on. I am proud of my heritage and culture. I embody the beauty and duality of masculine and feminine traits without denying either. I demand the world see me the way I want to be seen. As a result, my identities have evolved from strikes against me to badges of honor that I wear proudly. To walk this earth against society’s expectations of what womanhood looks like is revolutionary.

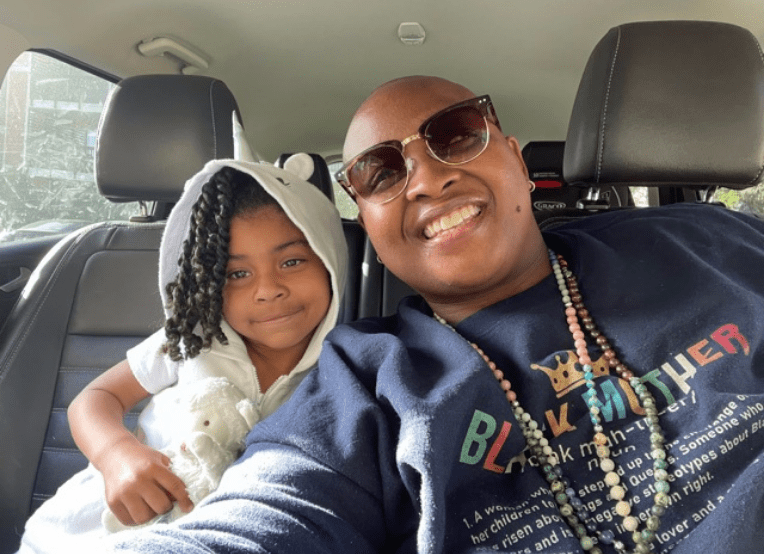

As parents to a four-year-old daughter, my wife, Dominique, and I strive to be the best parents. We have taken parenting classes and joined groups to prepare and round out our parenting techniques. It’s important for us to not only model Black queer love, good communication, and healing, but also to support and celebrate our daughter’s Blackness, femininity, intellectual curiosity, athleticism, and spunk. We support our daughter, Lyric Assata, in everything she does. We take the time to listen to her and truly understand her love languages. Dominique and I are just two Black queer womyn who’ve shared their visions and created the family we always wanted to have—and that’s revolutionary.

I’ve had an amazing experience since joining Haas in 2019. By far, Haas has been one of the best communities that I’ve joined. As a Black queer woman, I feel heard, my identities are celebrated, and I’m part of a diverse staff who support me. My colleagues and I regularly participate in Courageous Conversations where we discuss difficult topics like race, gender, and class. It’s rare to find a work environment where I can be my authentic self and I think much of that has to do with Haas’ Defining Leadership Principles (DLPs). Students Always is my favorite DLP because I’m an intellectual at heart and will forever be a student.

Now that I have transitioned from an admissions manager to an associate director, I feel like I have a seat at the table, I can make admissions decisions, and I can serve as a support system to all of our students, especially those who have similar backgrounds to me. When I was applying to college and graduate school, there was neither a blueprint nor a support system for me; I had to figure out everything on my own. But now, I can be of service to others.