The stock market has dominated 30 years of economic growth

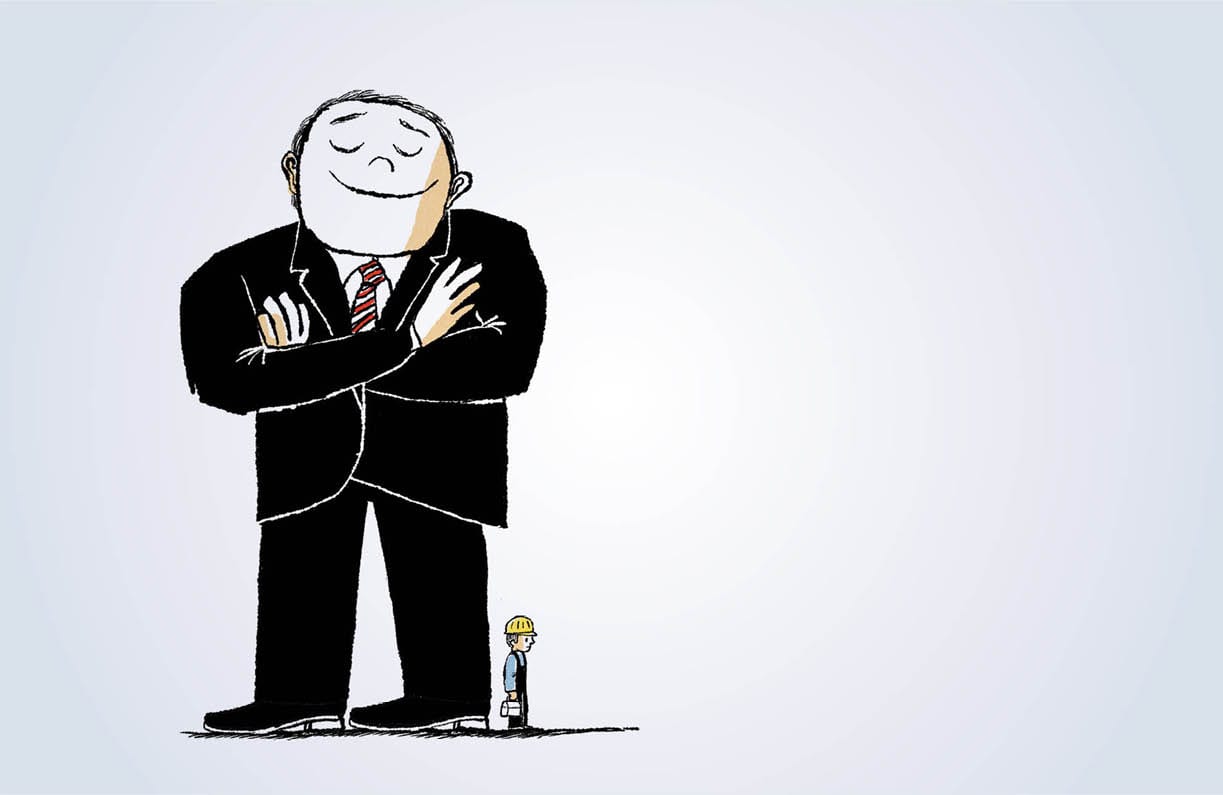

What’s behind the stock market’s gains over the past three decades? Not economic growth, says research by Haas finance Prof. Martin Lettau, but rather shareholders getting an increasingly bigger piece of the economic pie.

What’s behind the stock market’s gains over the past three decades? Not economic growth, says research by Haas finance Prof. Martin Lettau, but rather shareholders getting an increasingly bigger piece of the economic pie.

Lettau, the Kruttschnitt Family Chair in Financial Institutions, and colleagues from MIT and New York University, found that economic growth accounted for just 23% of the stock market’s rise over the past 30 years—compared with 92% in the prior three decades. The biggest driver? A dramatic shift in wealth from workers to investors, which has accounted for 54% of the stock market’s increase since 1989. Berkeley Haas sat down with Lettau to learn more.

What’s the widening chasm between the stock market and the broader economy?

Lettau: U.S. stock values have grown significantly faster than the economy over the last three decades. After adjusting for inflation, the stock market value of corporations outside the financial sector has risen an average of 8.4% a year since 1989, while the value of the economic output of corporations has climbed just 2.5% annually. By contrast, from 1959 to 1988, economic output was expanding faster than stock values.

What’s behind this trend?

Lettau: The bull market of the past 30 years comes largely from the capital sector getting more of the economic pie than the labor sector.

How big a factor has this shift been in pushing stock prices higher?

Lettau: We looked at the factors that standard financial theory considers to be drivers of stock prices. Falling interest rates and greater investor appetite for risk have each contributed 11%. Economic growth explains just 23% of the stock price increase. Meanwhile, we estimate that the reallocation of the rewards of production to shareholders and away from labor has accounted for 54% of the gains in stock market value since 1989. That’s a sharp turnaround from 1952 to 1988, when other factors accounted for just 8% of the rise in stock prices, while economic growth accounted for 92% of the increase.

Why has capital’s share of the pie grown and labor’s share shrunk?

Lettau: Our work doesn’t directly address the underlying reasons, but labor economists suggest plausible explanations. One is the decline in union power, which has weakened labor’s voice in setting wages. Another is outsourcing to cheaper domestic or international sources of labor, putting pressure on pay. Third is technology, which is replacing manual labor with intensive productive capital. Well-educated workers reap the benefits of robotics, but those without the skills in demand today are left behind.

What may be the sources of income inequality?

Lettau: Part of increased inequality could be due to the stock market. The overall economic pie is growing, but not at very high rates. The segment of the population that owns stocks has reaped the benefits of this growth relative to those who don’t own stocks.

Is this trend sustainable?

Lettau: It’s difficult to assess. Technological changes are unlikely to be reversed, but other factors could be reversible. If Congressional Budget Office projections for GDP turn out to be correct and the economic growth is sluggish, stock market investors will not see growth rates as in the recent past unless the labor share declines further. Since the end of the Great Recession, income growth has been robust and kept pace with corporate profits, but it is not clear whether this signals a short-term phenomenon or a change in long-term trends.