In honor of Black History Month, we’re running a series of profiles and Q&As with members of the African-American community at Haas. Follow the series throughout February.

In this interview, Matt Hines, MBA 19, discusses the challenges of being black in mostly white Atlanta private schools, how his parents championed Black History Month, and the Haas course that helped him share his feelings about race.

Tell me about what is was like growing up black in your community.

While Atlanta is very diverse, the community I grew up in was not very diverse at all. I went to private school my entire life and grew up in a fairly white community. The first black student I remember having in my class was in fifth grade. For a while I struggled with kids at school assuming I should act a certain way, talk a certain way, or listen to a certain kind of music—kids having expectations for what I should or shouldn’t be. Being comfortable and confident with who I am took a while for me, in relation to race, and it’s definitely something I still work on.

Did you have experience with Black History Month as a child?

Black History Month wasn’t a big thing when we first got to our school in Atlanta, but I remember both my parents petitioning the school and setting up their own events every year when they would bring in speakers. We watched the movies Ruby Bridges (about a six-year-old African-American who helped to integrate the all-white schools of New Orleans) and Little Rock Nine (about The Little Rock Nine group of nine black students who enrolled at formerly all-white Central High School in Little Rock) during Black History Month whenever they came on TV. When we lived in San Antonio (before Atlanta), my sister and I participated in the Mahogany Brain Challenge in our church, an African-American history trivia challenge between kids in various churches across the city. We’d study black history with other black youth and learn facts about black leaders such as George Washington Carver and Harriet Tubman.

Who are some African Americans who inspire you?

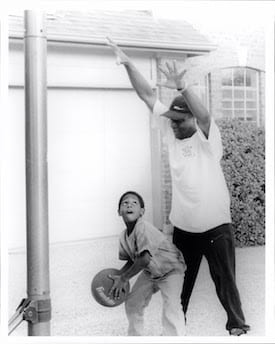

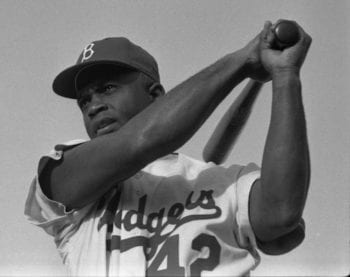

When I was a kid it was always Jackie Robinson. I remember having a picture of him in my room growing up and reading autobiographies about Jackie Robinson and admiring everything he stood for, everything he fought for. I have since enjoyed reading Malcolm X, appreciating both the vigor with which he sought to uplift the black community and his commitment to introspection and learning that allowed him to continually shift his rhetoric throughout his life. Today, Ta-Nehisi Coates is one of my favorite authors. He writes a lot about his relationship with his father and then his son. It’s something I think about, how my father handled having a black son, and the conversations that we had and are still fortunate to have today.

What can be done in the schools to build more understanding about black history?

The Dialogues on Race course at Haas has been an exceptional opportunity for me to start to get more comfortable discussing topics about race in my life. (Hines is a course co-facilitator with America Gonzalez). The goal of the class is to force us to think introspectively about our own racial identity and our own biases and the way we interact with society and to really dive into the historical context of racism—the institutional and systemic racism—that exists in the country. For me, it’s been very powerful to get more comfortable hearing my own thoughts about race and to speak them with a group of peers in a safe environment. That’s a model that I think can be used elsewhere.

How do you feel about speaking frankly in front of white people in the classroom?

I feel comfortable talking about this subject with black people and I do it all the time. The goal is to speak about it with people who don’t look like you. If we look at the way this country is run it is still dominated by white people who are making the decisions and have the capacity to make change. In my mind, no significant change can happen without white people on board so we have to have these conversations with them and we have to create allies.

What do you wish others knew about what it means to be black in the U.S.?

For me, growing up black has been mentally taxing more than physically taxing. It’s constantly second-guessing every interaction I have with someone. Are they genuine in the way they look at me and talk to me? Am I the the first black person they’ve talked to this month and has that changed the way they talk to me? There are little microaggressions that get to you, like when I’m in line at the grocery store or the bank there have been multiple times when a white person has just “accidentally” walked in front of me and that person acts as if he or she didn’t see me. It’s not the end of the world, but you’re thinking: Is this person even worth wasting the energy on or do I want to just let it go?

Beverly Tatum (the president of Spelman College and the author of Why Are All The Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?) talks about how we live in a racialized society that is impossible to escape and that we are all complicit. She used the analogy of breathing in the smog in a polluted city and that it’s truly impossible to escape unless we are consistently putting in counter measures to counteract the racism and segregation that exists in our society today. The first piece of that is acceptance and I don’t think that we’re at a point of acceptance. If we do ever get to a point of acceptance we have to teach the truth in our schools and the truth about our history.