Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, medical research around the virus has exploded in the United States. And yet, only one drug, Remdesivir, has, so far, been tested in clinical trials and approved by the FDA.

What some might call “miracle cures” that can heal COVID-19 patients in just days, are only available to high risk patients in the U.S.. Other treatments - taken orally or by inhalation, which have been proven to reduce the viral load significantly - are not yet available here. Meanwhile, doctors in Great Britain launched the largest clinical trials and history and netted several effective treatments. In an attempt to find out why, NBC Bay Area’s Investigative Unit uncovered a U.S. research system that - despite brilliant science and vast resources - is not designed to keep pace with the urgent demands of a pandemic.

Instead, the system is made up of individual, competing interests that can slow the pace of medical discovery and discourage some innovative approaches that are encouraged in other countries around the world.

I know what's going on when COVID enters your body.

Josipa Matusich, Clinical Lab Scientist

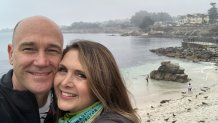

Take for example Josipa Matusich. Matusich works as a clinical lab scientist in Santa Clara. That’s why she feared the fever and chills that swept across her body last March could spell disaster.

Her lifelong battle with rheumatoid arthritis put Matusich on a drug regimen that weakened her immune system, and she worried about what COVID-19 would do to her.

"I know what's going on when the virus enters your body and how quickly it disseminates,” she said. And later tests confirmed Matusich’s fears. She had contracted COVID-19.

A Kind of Magic Bullet for COVID-19

So when Matusich heard about a kind of “magic bullet” for COVID-19, available at Stanford Medical Center for high risk patients like her, she immediately booked an appointment.

“We have a large number of our population that's immunosuppressed,” said Dr. Upi Singh, Division Chief of Infectious Diseases at Stanford. Dr. Singh and her team developed a monoclonal antibody treatment for people like Matusich.

Monoclonal antibodies are created in a lab. Scientists expose billions of cells from the immune system to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the specific virus that causes the COVID-19.

Out of those billions of cells, the scientists then isolate the one that works best to prevent the spike protein from entering the human cell. They mass produce that immune cell and inject it into patients.

“It's an infusion,” said Dr. Singh. “You have to get an I.V. and it goes into the body over (the course of) an hour and then we watch them for an hour.”

“A nurse came, picked me up at the parking garage, took good care of me,” said Matusich. She received her infusion four days after testing positive for COVID-19. “Then I drove home. Everything was very easy,” she said. The treatment worked for Matusich. “After a few days, I start feeling better and, here I am. I'm all good. Good to go!” she said.

“It's been well studied and it's very safe and it's effective,” said Dr. Singh. “And the data show that it decreases the symptoms, decreases the virus in the nose. So, you're less likely to spread it to a family member. And most importantly, it reduces your chances that you end up in the emergency room or in the hospital.”

Powerful COVID Treatments Only Available for High Risk Patients

But at the moment, here in the U.S., monoclonal antibodies are only authorized for emergency use in high risk patients. In fact, the FDA has only approved one drug to actually treat COVID-19 once you get it: Remdesivir, made by Gilead Sciences, based in Foster City.

A Study in the New England Journal of Medicine found Remdesivir shortened hospital stays by five days in COVID patients – and reduced deaths by about 5% compared to a placebo.

Meanwhile, using far fewer resources and less money, Great Britain has run about ten treatments through large clinical trials and found several effective treatments for COVID-19 patients.

Inexpensive Steroid Reduces COVID-19 Sickness by 30% in Great Britain

“The breakthrough was in summer 2020 when we found that dexamethasone... dampens down inflammation,” said Sir Martin Landray, Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology at Oxford University in the United Kingdom, adding that dexamethasone, a steroid, “reduces the risk of dying for the sickest patients by up to a third.” And he says, an entire course of treatment costs about $20.

British doctors also discovered that Tocilizumab, a rheumatoid arthritis drug, reduces inflammation in COVID-19 patients. And monoclonal antibodies like Matusich received are more readily available for all patients in Great Britain not just high risk experimental patients as they are here in the U.S. In fact, the Investigative Unit found that since the start of the pandemic, British hospitals have outpaced the U.S. in developing new treatments for COVID patients.

One thing is clear - there is no lack of research on COVID-19 treatments in the United States.

One drug currently in development is Molnupiravir. It can be taken orally in the early days of COVID-19 infection and has shown strong results in the lab and in animal trials.

“There's some preliminary data, you give it to people, their virus levels drop dramatically.” said Dr. Robert Shafer, professor of medicine in the Infectious Disease Division at Stanford. Dr. Shafer and a team of scientists have published a comprehensive review of COVID-19 antiviral therapies, along with a plan for improving the research timeline. Yet another drug uses a version of the human body’s natural immune defenses: interferon, to battle the coronavirus. It can be inhaled at home if someone suspects they’ve been exposed to the virus.

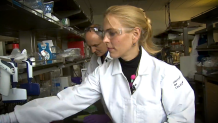

And, at UC Berkeley, biochemist Julia Schaletzky and her staff tested thousands of approved drugs to see if just one would make Remdesivir better at killing the virus.

"I think everybody on the team felt strongly we have to do what we can do against COVID,” said Dr. Schaletzky.

After months of searching, they got a hit.

“It completely eliminates the virus in cells, which is great. But that's just a first step,” said Eddie Wehri, a scientist at UC Berkeley’s Center for Emerging and Neglected Diseases.

“When there's something like this where there's really big urgent need, it'd be good to have some sort of a faster pipeline to get something like this out,” said Wehri. Right now, “there’s a lot of hurdles.”

So why isn’t more of this research turning into treatments for victims of COVID-19 across the country?

We don't notice on a daily basis how slowly we move.

Dr. Derek Angus, Chief Innovation Officer at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

“COVID has shone a light on the inefficiency of the system,” said Dr. Derek Angus, Professor of Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh and Chief Innovation Officer at UPMC.

U.S. Research System Not Designed for Fighting a Pandemic

“We have a clinical research infrastructure that works perfectly well in peacetime,” said Dr. Derek Angus, “but it (the system) was left woefully inadequate for the speed of knowledge generation that would have been most helpful during this epidemic.”

One problem, said Dr. Angus, is that U.S. researchers rarely collaborate with health providers. That’s a common practice in Great Britain which, he says, expedites development of new treatments.

“That has not happened that much in the United States,” said Dr. Angus. “We are very separate organizations.”

Dr. Angus and others say that another impediment to large-scale clinical trials is that U.S. healthcare lacks central leadership. That’s much more easily accomplished within the British single-payer system. Further complicating the process in the U.S. researchers have to directly compete with each other for funding.

“It's nice to have a market of ideas, universities competing for federal funds to get one idea championed over another. It's sort of in our DNA,” said Dr. Angus. “It's just that we don't notice on a daily basis how slowly we move.”

Doctors and scientists told NBC Bay Area that this COVID-19 pandemic has been a huge wake up call for clinical researchers in the United States. They say that while health care here is not centralized, the U.S. does have large health systems which can, with the right leadership, launch major clinical trials to fight future pandemics.

"I feel, actually, this pandemic could be a good catalyst for improvements in many areas if we take it seriously and if we allocate enough time and get everybody thinking to take this passion that we all have to contribute to the solution and make some lasting changes,” said Dr. Schaletzky.