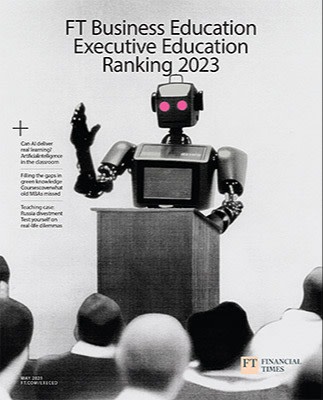

Can artificial intelligence deliver real learning at business school?

Simply sign up to the Artificial intelligence myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

For many people, ChatGPT appeared to come out of nowhere — a startling wake-up call to the potential opportunities and threats of artificial intelligence (AI). But Zsolt Katona, professor of marketing at California’s Berkeley Haas School of Business, was using a forerunner, GPT-2, as early as 2019, both to teach executives on the technology leadership programme about emerging tech and to write scripts for the videos that accompanied his course.

“It was a very tedious task to write scripts that I’d then read from a teleprompter,” recalls Katona. “I’ve never been good at writing nice-sounding text, either in English or my native Hungarian. But, even back then, the scripts generated were pretty good.”

Katona has little time for ChatGPT naysayers. “I love it. It’s a fantastic educational tool,” he says. “I remember what it was like in high school when there was no internet. Just like Google Search for a previous generation, ChatGPT will become how people access knowledge in this generation. It means we can be much more efficient in education, including executive education.”

ChatGPT has caused waves because it uses generative AI language models, enabling it to create new content based on the information it is provided in the form of text, images or audio. The quality of its output depends on the quality of the input it receives. Professor Christian Terwiesch at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School found that the chatbot was able to pass the final exam for his school’s MBA, scoring between B- and B on the Operations Management Course.

In his research paper, Terwiesch predicted ChatGPT’s “remarkable ability to automate some of the skills of highly compensated knowledge workers in general and specifically the knowledge workers in the jobs held by MBA graduates including analysts, managers and consultants”.

Business school faculty are divided. Some worry generative AI may turbo-charge academic misconduct in assessments. Others, such as Katona, are already planning to create class activities in which students use ChatGPT to solve problems by asking it questions, or work in groups to analyse the accuracy of information it provides. At the least, interactions with generative AI might be expected to stoke participants’ curiosity and inspire them to ask more questions.

Within executive education specifically, generative AI could be used to create simulations that mimic real-world business interactions, such as negotiations and sales pitches. Executives could use AI as a “study buddy”, with which they practise critical thinking and problem-solving skills. The conversational nature of ChatGPT responses means participants could get immediate personalised feedback beyond that a time-pressed faculty can offer.

Business simulations, idea generation and sparring are among the AI-powered activities under way at Insead in France. Adjunct professor Adrian Johnson has integrated ChatGPT into simulated negotiations, where executives haggle with the AI.

Insead Strategy professor Phanish Puranam runs organisation design exercises, in which students use ChatGPT to help generate a wide variety of possible solutions. He is also thinking of using it as a sparring partner, with algorithms critiquing executives’ thoughts and asking them for more explanation.

“In their own businesses, managers will have to view AI through a double filter,” Prof Puranam says. “Will it actually improve how their organisations work, and will it make them more or less human-centric?”

Polimi Graduate School of Management in Milan uses an AI-powered tool called Flexa, developed with Microsoft, to provide career coaching. Participants use the platform to decide where and how to access a personalised learning path, starting with an assessment phase evaluating what skills they need to improve. Flexa then uses AI to create tailored programmes for each user, who can access about 800,000 pieces of learning material, including self-paced digital courses, webinars, podcasts, articles and case studies.

“The technology still needs to be evolved,” says associate dean Tommaso Agasisti. “We don’t have many tools yet to help executives work with real problems using artificial intelligence, but we think that will happen very soon.”

Alain Goudey, associate dean for digital at Neoma Business School in France, agrees. “AI can analyse the learning preferences, strengths and weaknesses of individual students, allowing business schools to tailor their exercises, content and curriculum accordingly.” The school uses AI to identify slow and fast learners, to help both reach their potential. “AI acts like a companion to the students and will help the faculty to be more focused on specific challenges or better in-class learning experiences,” he says.

Russell Miller, director of innovation for executive education at Imperial College Business School in London, is also eager to see schools use AI to create non-linear, adaptive learning targeted to students’ needs. He believes it can assess knowledge gaps and where extra support is needed. “It would mean learners spending less time working through things they already know,” he notes.

Generative AI can even help business schools deliver a more inclusive experience, suggests René Eber, lecturer at HEC Paris Executive Education. “English presentation skills are still a major barrier for some participants,” he says. “We get them to use ChatGPT to tell a more convincing story when pitching their ideas in front of the jury, as well as written reports. It means an equal playing field for participants from all backgrounds.”

Comments