Does Station Competition Drive Gas Prices?

New Energy Institute working paper finds retailers cut prices when rivals are nearby.

Gasoline is virtually the same product no matter where you buy it, yet retail prices range considerably. In my neighborhood last week, gas prices ranged from as low as $4.29 to as high as $5.59. According to GasBuddy, gas prices in New York range from $2.99 to $4.99, in Chicago from $2.79 to $4.99 and in Los Angeles from $3.95 to $6.35.

There are many explanations for these widely varying prices, but, in part, this is about competition. Or, perhaps more to the point, about the lack of competition in certain local markets. When a new gas station opens we generally expect this to push prices down, and, potentially, to lead incumbent stations to provide better service.

In a new Energy Institute working paper, Shaun McRae, Enrique Seira and I test this hypothesis using a remarkable dataset that describes every single gas station in Mexico. Over our sample period 2017 to 2022 we observe the entry of over 1,000 new gas stations and we use these events as natural experiments to measure the effect of competition on prices and service quality.

Thousand New Stations

In 2017, at the beginning of our sample period, there were 11,645 gas stations operating in Mexico. We refer to these stations as “incumbents”. Between 2017 and 2022, 1,072 new stations entered. We refer to these stations as “entrants”. Entrants are new stations opened in locations where there was previously no station; so an ownership change, for example, is not an entrant.

—

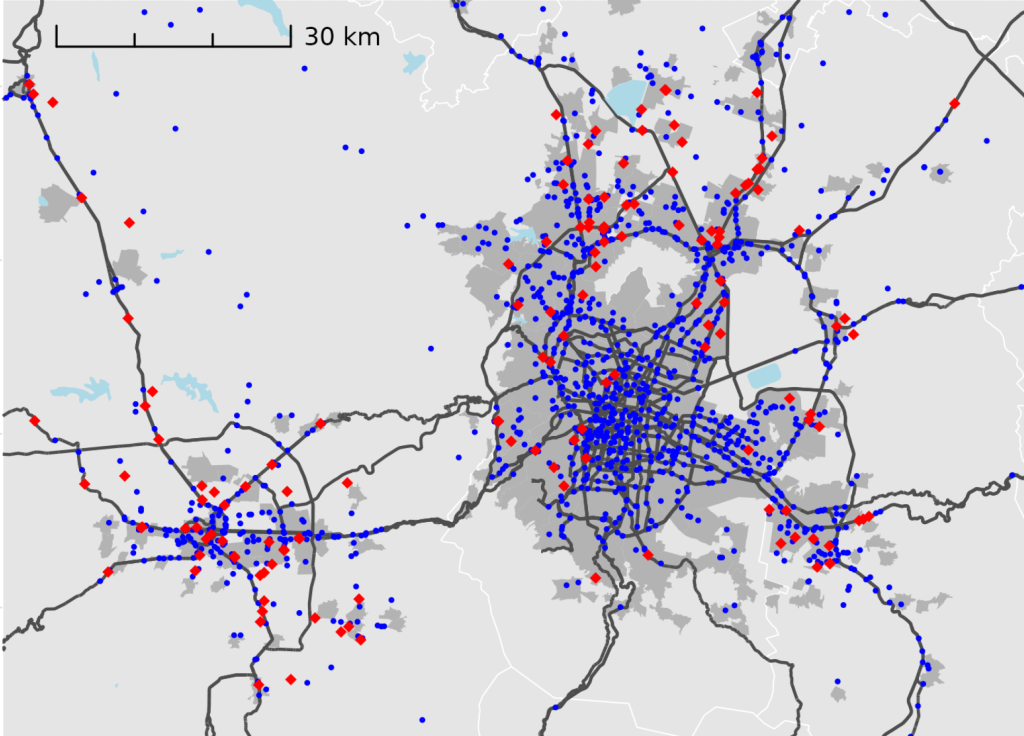

To get a sense of our data, the map above shows the Mexico City metropolitan area. Incumbents are shown in blue, and entrants are shown in red. In this metropolitan area alone, there are dozens of entrants, mostly around the periphery as well as throughout Toluca, the city to the west of Mexico City.

One of the key sources of variation that we take advantage of in our analysis is that entry affects some incumbents more than others. For example, during our sample period many incumbents, particularly in Mexico City’s dense urban core, experienced no nearby entry. Other incumbents had stations open up right next door.

Competition Pushes Prices Down

Compiled from various administrative sources, our core dataset describes daily retail prices for regular gasoline, premium gasoline, and diesel. To define local markets, we match each station to the road network and count the number of competitors within three minutes driving time. We then compare local markets before and after entry, using other stations farther away as a control group.

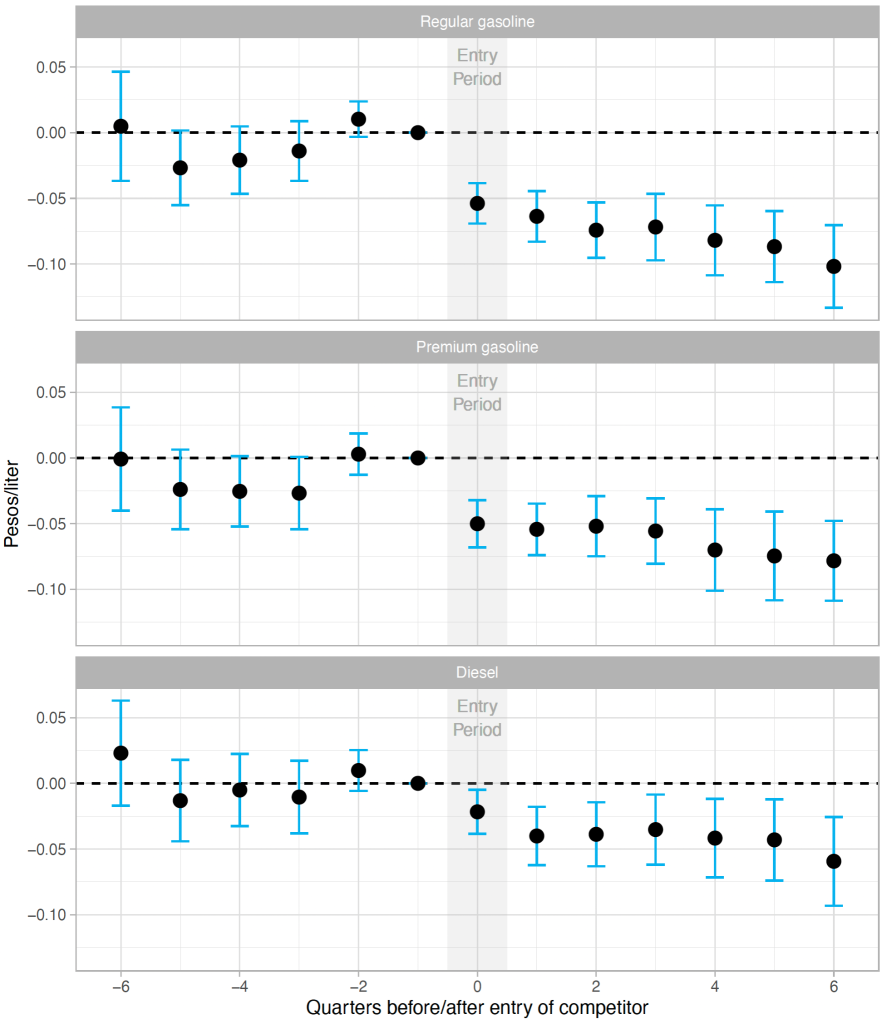

The effect of competition on prices can be summarized using the event study figures below. The horizontal axis shows time in quarters before and after the entry of a competitor within three minutes driving time. We normalized the data so that the quarter of entry is equal to zero for each event.

—

During the quarters leading up to entry, prices tend to be approximately flat. After entry, prices decrease significantly for all three refined products. Prices for regular gasoline decrease sharply by 0.05 pesos per liter in the first quarter after entry and continue to decline in subsequent quarters. Similar decreases occur after entry for premium gasoline, while the decreases for diesel are somewhat smaller.

These are modest effects. For example, a typical price for regular gasoline is 17 pesos per liter, so our estimates imply less than a 1% price decrease. Still, while this is a small effect from the viewpoint of consumers, it is a large effect from the gas stations’ perspective, equivalent to a 6% decrease in retail margins.

Distance Matters

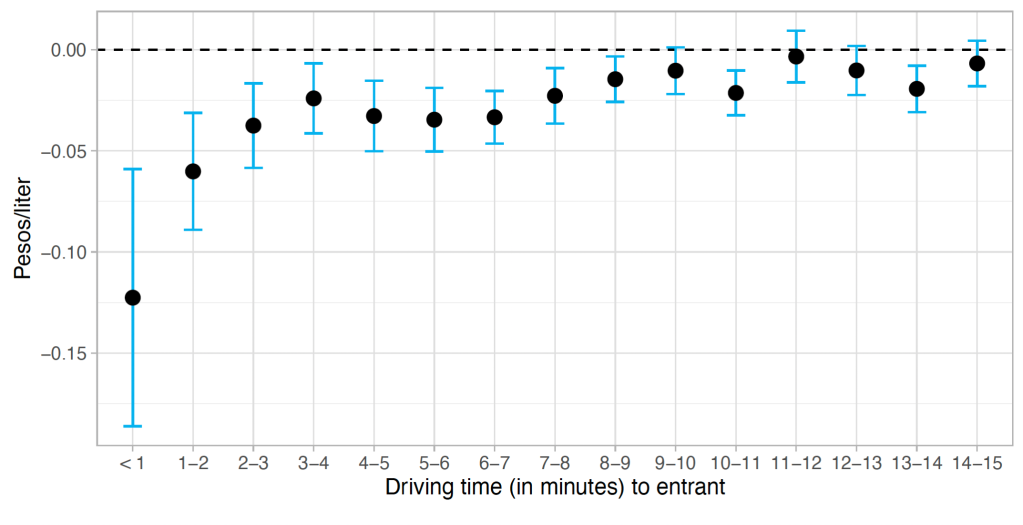

We also find that effects are larger when the entrant is within 1 and 2 minutes driving time. The figure below shows the effect of entry by driving time. There is a clear pattern, with the effect of entry attenuating for stations farther away. Within 1 minute, an entrant reduces regular gasoline prices by 0.12 pesos per liter. Between 1 and 2 minutes the effect is about half as large. Effects get smaller further away but remain statistically significant for up to 9 minutes. Past 9 minutes, the effect of an additional competitor is close to zero and mostly not statistically significant.

—

Monopoly Incumbents

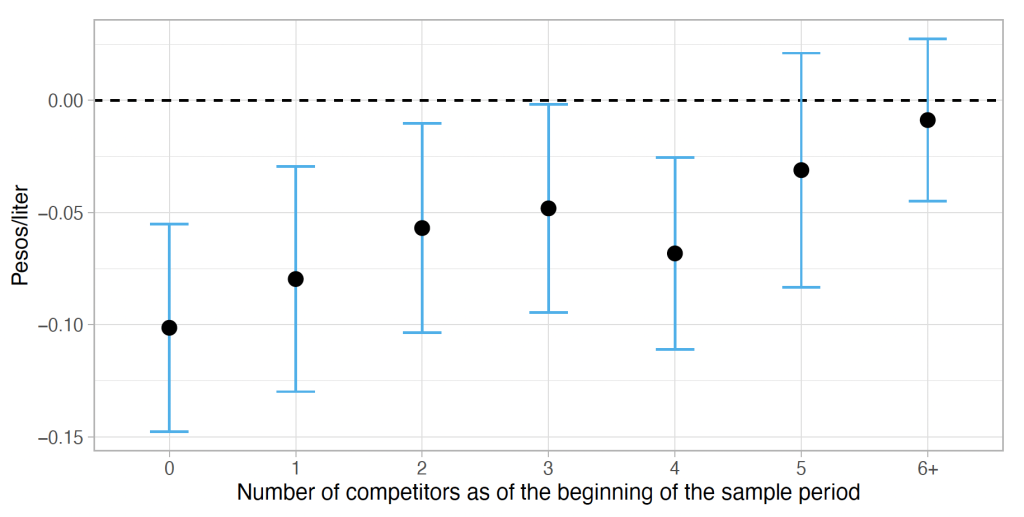

We also test to see whether effects differ by initial market structure. Some incumbents started out all by themselves, with zero competitors within three minutes driving time. Other incumbents were initially in markets that were already more competitive, with 1, 2, 3, or more existing competitors. The figure below shows the effect of entry broken out by the initial number of competitors.

—

The results match what we would expect. For an incumbent that initially had zero competitors – that is, a monopoly incumbent – an additional entrant reduces prices by 0.10 pesos per liter. This effect declines by more than 20 percent for the case of a market that initially had one competitor (a duopoly), and continues to decline for markets with 2, 3, 4+ initial competitors.

But Are the Bathrooms Gross?

I said at the beginning that gasoline is virtually the same product everywhere. But even if gasoline itself is virtually the same product, gasoline stations themselves are not. Our paper next turns to service quality. The relationship between competition and service quality is more complex and has received less attention in the previous literature because it is so hard to measure.

We use several novel sources of data to measure station quality. One of our measures comes from inspections of gasoline station bathrooms. In recent years, the Mexican consumer protection agency has performed over 26,000 bathroom inspections.They check whether the station has a working bathroom, evaluate its cleanliness, and check for soap and other features.

—

Using the same empirical strategy, we test whether service quality changes when a new gasoline station opens nearby. These estimates are less statistically significant, but results for all three measures suggest that quality improves with more competition. Thus, overall, it appears that gasoline stations are competing on both price and quality.

Competition and Consumer Benefits

Our paper has implications for ongoing policy reforms in Mexico. The previous decade has been a period of unprecedented change in Mexican gasoline markets, and there remains considerable uncertainty about the direction of competition policy moving forward. Our empirical framework, data, and results are directly relevant to these conversations, particularly regarding the role of competition in improving outcomes for Mexican consumers. They also suggest issues that California should examine as part of investigating its Mystery Gasoline Surcharge.

The results also give broader insight into the importance of competition among small businesses. Given that a large share of household consumption occurs at small local businesses like gasoline stations, it is important to understand the causes and consequences of market structure in these industries.

—

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Bluesky and LinkedIn.

For more see, Davis, Lucas, McRae, Shaun, and Seira, Enrique. “Competitive Effects of Entry in Gasoline Markets,” Energy Institute Working Paper, (December 2023), WP-345.

Suggested citation: Davis, Lucas. “Does Station Competition Drive Gas Prices?” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, December 11, 2023, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2023/12/11/does-station-competition-drive-gas-prices/

Categories

Lucas Davis View All

Lucas Davis is the Jeffrey A. Jacobs Distinguished Professor in Business and Technology at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. He is a Faculty Affiliate at the Energy Institute at Haas, a coeditor at the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He received a BA from Amherst College and a PhD in Economics from the University of Wisconsin. His research focuses on energy and environmental markets, and in particular, on electricity and natural gas regulation, pricing in competitive and non-competitive markets, and the economic and business impacts of environmental policy.

In 1973 the ARCO station I worked at charged a few cents more per gallon than the SOHIO station a quarter of a mile away. We were closer to the entrance onto 271. Some folks came to the station to use our restrooms rather than use those at the Mayland Cinema just down the road. Both stations were full service. Diesel was not available at either station.

#2 diesel is still very expensive here in Ohio. A Shell station opened earlier this week close by- regular was $2.85/gallon this morning and diesel was $3.99/gallon. We filled up at Sams club with 93 octane high test for $3.30/gallon a week ago.

I don’t want to sound naive, but here in California gas price are supposedly much high due to high taxes, not just competition.

The tax foundation notes taxes per state-

https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/state/state-gas-tax-rates-2023/

The foundation notes that their table (77.9 cents per gallon for CA) does not include carbon taxes. CBS8 noted those fees here-

https://www.cbs8.com/article/traffic/gas-prices/gap-between-californias-gas-prices-and-the-us-has-never-been-larger/509-17522867-a344-4cbc-bc5d-ac617eb21268

“Taxes and fees

For every gallon of gas in California, we pay:

54 cents in state excise tax: among the highest in the nation

18.4 cents in federal excise tax

23 cents for California’s cap-and-trade program to lower greenhouse gas emissions

18 cents for the state’s low-carbon fuel programs

2 cents for underground gas storage fees

An average of 3.7% in state and local sales taxes

“Local governments are the ones that are really making out well because they are getting a percentage-based tax,” Langley pointed out. “It’s not a flat excise tax.”

I would dispute that the gasoline is virtually the same everywhere. In California, one doesn’t know that the gas has ethonal until it’s too late. Clearly, the MPG with ethanol is about 10% less.

My anectdotal experience tells me certain stations are consistantly lower and others consistantly high, but all float down and (mostly) up at the whim of the oil companies. If there’s any reason, justifiable or not, to raise prices, they immediately go up, but the in the converse, they slowly go down.

Another trick is ratcheting: prices suddenly go up, slowly down, but not to the level before the sudden up.

There is no competition.

Now, about the study. It may be true in Mexico, in and around Mexico City, but Mexico is culturally different than the USA.

Good Study, though. Thorough, well thought out.

Oh, and by the way, you may not have noticed that the color of the sea is changing and more extreme weather conditions are upon us. I read that the nearly every climate scientist tell us that if the if we don’t reduce green house gasses 80% of the species on Earth will go extinct. Of course they’re wrong because Trump says so.