Do High Interest Rates Threaten the Green Transition?

Increased borrowing costs make long-term investments more expensive.

Depending on which headlines you’ve been reading, you might have gotten the sense that all is not well with the green transition. Recent weeks have seen a bevy of dropped projects and tempered ambitions. Orsted canceled a high profile offshore wind project in New Jersey. One estimate suggests that a full 30% of state-contracted offshore wind projects have been scuttled. GM and Honda nixed a major partnership to make electric vehicles, while GM dropped its EV production targets and Ford announced a major delay in EV spending. The iShares Global Clean Energy ETF, a benchmark index of clean energy stocks, was down 30% year-to-date last week, against a 7% increase in the Dow.

Wind projects like these are evidently not headed to the Jersey Shore. (Photo source: NYTimes)

If you click through and read these stories, one common thread is the role of higher interest rates. Central banks have been holding interest rates “higher for longer,” and this change in borrowing conditions has become an oft-cited reason for green project slowdowns. Are today’s interest rates a real roadblock, or just a quick bump in the road?

Why are high interest rates bad for the green transition?

Higher interest rates make it more expensive to borrow or spend money today. Higher borrowing costs make it more expensive to invest in fossil fuels as well as green technologies, but higher borrowing rates present a relative disadvantage for green technologies for three main reasons.

First, green technologies tend to trade off higher up front costs against lower operating costs, which means that borrowing costs have a higher proportional effect on green investments. This is most acute for solar and wind, which get free fuel from nature and thus have total costs heavily skewed toward upfront capital and installation. Natural gas plants, in contrast, have a more balanced mix of costs and are thus less sensitive to an increase in financing rates. The same principle applies to EVs, which exchange a higher up front purchase price for lower cost per mile, as compared to gasoline alternatives.

Second, green technologies are inherently about change. Higher borrowing costs slow overall investment and slow down churn. When borrowing is hard, households will hold onto their existing vehicles, air conditioners and furnaces for longer, which slows down the natural turnover that favors cleaner goods. On the supply side, electrification requires massive investment in transmission, and carbon capture calls for new pipelines and lots of capital.

Third, more nascent green technologies–think storage, direct air capture and electrolysis–still need a heavy dose of pure research and development. R&D costs more when money is expensive, so a world with higher interest rates favors incumbents.

How much have interest rates changed, and is this enough to matter?

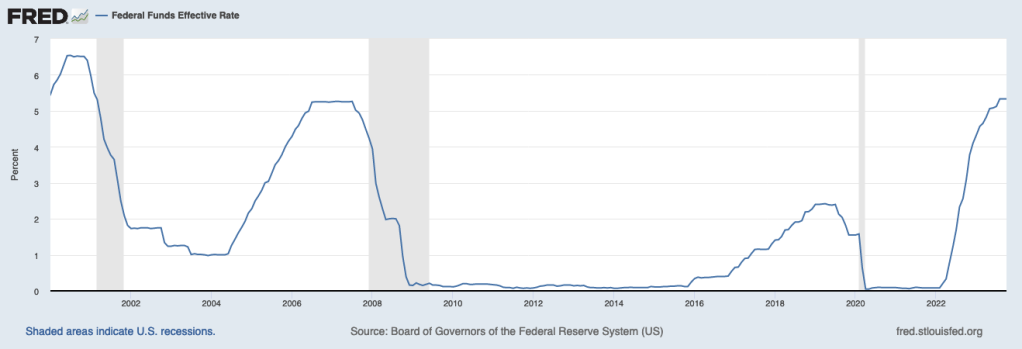

The most salient benchmark interest rate in the US is the Federal Funds Rate, which governs interbank lending and which the Federal Reserve Board directly controls. The effective Fed Funds Rate currently sits at 5.25%, a 22-year high. The Federal Funds Rate spent most of the last dozen years at a nice cozy 0%, and we have to rewind to the Bush Administration to find rates higher than we have today.

The Effective Federal Funds Rate is at a 22-year High (Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve)

Estimates from the IEA suggest that a 5% increase in the borrowing costs applied to a project raises the levelized cost of wind or solar by as much as 50%, while having a single digit impact on a new gas plant.

And, in case you missed it, the cost of renewables has risen since 2020. The initial shock was due to commodity price spikes, which have since stabilized, but elevated financing costs mean that the IEA projects that the levelized cost of solar and wind in 2024 will remain higher than their pre-pandemic benchmark.

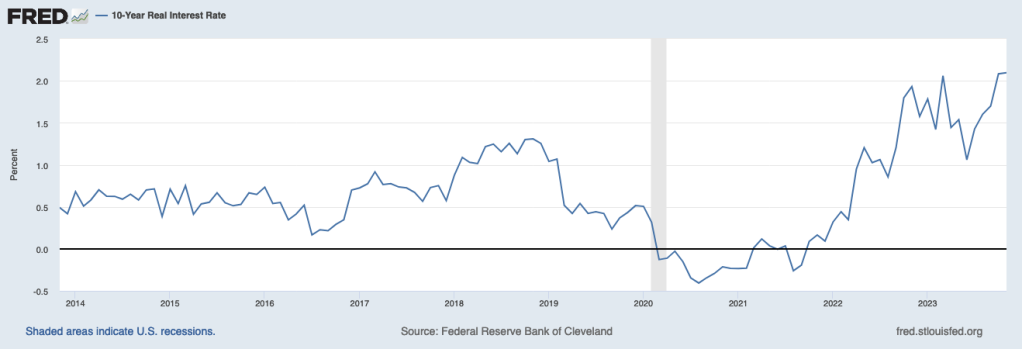

On the other hand, things may not be that bad

A five percent swing in interest rates is a big deal for borrowing. But, the Federal Funds Rate is a nominal rate, a rate that does not adjust for inflation. We have high interest rates in part because we are reckoning with inflation, and economists normally think the thing that matters most for investment is the real interest rate, which adjusts for inflation. The change in borrowing costs looks less dramatic when one adjusts for inflation. The 10-year real interest rate on US Treasuries calculated by the Federal Reserve, which projects inflation based on a collection of forecasts, shows something closer to a 2% increase over the last couple of years.

Real Interest Rates are Elevated, but Far Less than the Nominal Rate (Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve)

A 2% increase is nothing to sneeze at, but conventional estimates show that, even with elevated financing costs, renewables remain the cheapest source of power. Modest moves in the interest rate will push marginal projects out of the money and slow down renewable deployment, but it won’t flip the big picture. So, consider this a notable headwind, but not an existential threat.

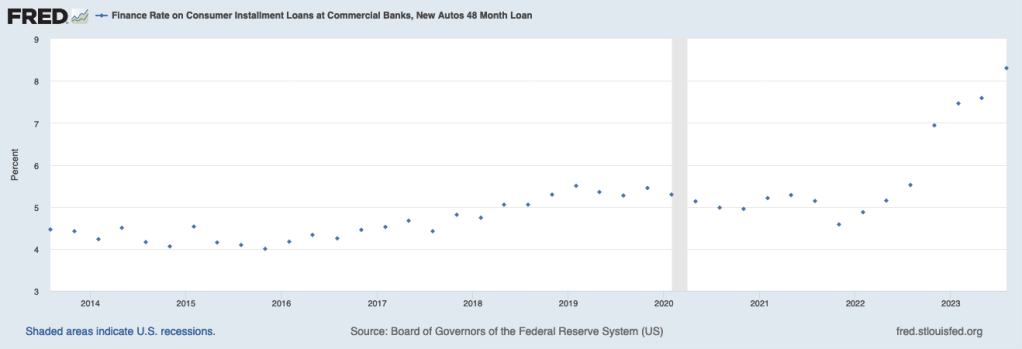

While economists argue that the inflation-adjusted real interest rate is the most relevant for decision making, it may well be that households are sensitive to nominal rates that affect their perception of borrowing costs. The Fed collects data on the interest rate on car loans, which shows that the average rate for new car loans has recently jumped above 8%.

Nominal Rates on Car Loans have Jumped, Making EVs a More Expensive Option (Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve)

Conventional wisdom suggests that car buyers focus on monthly payments. The average EV costs more than $50,000. If a car buyer financed the entire amount with a four-year loan, a jump from 4% to 8% in the loan rate would increase the monthly payment by about $90. This is more than the drop in monthly payments due to the $7,500 federal EV tax credit, which would knock down the monthly payment in the same scenario by around $80.

But, most buyers won’t finance the entire amount, and higher interest rates raise the monthly payment of internal combustion engine vehicles as well, which are selling for only about $5,000 less on average. For a consumer choosing between an EV and a conventional vehicle, if the EV price premium were $10,000, the jump from 4% to 8% on a 48 month loan only changes the relative payment by about $20 a month. This might still matter for some car buyers, but my suspicion is that higher borrowing costs will mostly impact EV purchases by depressing overall new car sales, as buyers hold onto existing cars longer, rather than causing them to choose a new conventional vehicle instead of a new EV.

Looking ahead

Last year, Reuters surveyed a bunch of economists, and they agreed that higher interest rates were of mild concern for the green transition. I tend to agree–whether real interest rates are 0% or 2% or 3%, the green transition in the US is likely to march along, though there will be some slow down on the margin.

Recent news from the most hawkish Fed governors suggests the current rate “pause” may be extended. We may already be looking at peak rates. So, we should keep our eye on these macro factors, but the bigger issue with financing and the green transition is probably about ensuring access to capital in lower-income countries, not worrying about the Federal Funds Rate in the US.

This view, however, hinges critically on the presumption that policy support from the IRA and related mechanisms remains robust. And high interest rates may yet have a role to play in this regard.

Most provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act expire in 2025, which means that after next year’s election, Washington will almost certainly have to reckon with tax policy. This fiscal debate will happen in the shadow of a rapidly growing national debt, fueled by both recent spending (including the IRA) and rising debt financing costs due to higher interest rates. Recent estimates from the Congressional Budget Office projected that the annual cost of financing the national debt would exceed $600 billion in 2023 and total $10 trillion in the subsequent decade. The federal debt takes on a completely different dynamic at higher interest rates, and these budgetary pressures could quickly rise in importance, as argued here.

How might this impact environmental policy in the 119th Congress? In one (wildly?) optimistic scenario, a need for revenue could reignite interest in pricing carbon. On the other hand, a higher debt load offers a reason (or a pretense) for gutting the aggressive green subsidies passed by the Biden Administration. In a twist of irony, to get lower rates and thus ease debt financing costs, we may need a fair bit of inflation reduction in order to save the Inflation Reduction Act.

Of course, which path we take depends most importantly on who sits in the White House and who controls Congress in 2025. Thus, if high interest rates today impact the electoral outcome itself–either by taming inflation or by fueling perceptions of a poor economy–that may well be the most significant way in which the Fed’s decisions on rate’s today affect the green transition of tomorrow.

Suggested citation: Sallee, James. “Do High Interest Rates Threaten the Green Transition?” Energy Institute Blog, UC Berkeley, December 4, 2023, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2023/12/4/do-high-interest-rates-threaten-the-green-transition/

Categories

James Sallee View All

James Sallee is a Professor in the Agricultural and Resource Economics department at UC Berkeley, a Faculty Affiliate at the Energy Institute at Haas, and a Faculty Research Fellow of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Before joining UC Berkeley in 2015, Sallee was an Assistant Professor at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago. Sallee is a public economist who studies topics related to energy, the environment and taxation. Much of his work evaluates policies aimed at mitigating greenhouse gas emissions related to the use of automobiles. Sallee completed his Ph.D. in economics at the University of Michigan in 2008. He also holds a B.A. in economics and political science from Macalester College.

“If you click through and read these stories, one common thread is the role of higher interest rates.” Another common thread among new generation starts is all are “renewable”.

Conspicuously missing from the list is that other green technology, nuclear energy. Like renewables, nuclear energy has high upfront costs. Also like renewables, it generates no carbon emissions. Unlike renewables, however, nuclear generates reliable, baseload power. Due to pipeline constraints, its generation is even more reliable than natural gas, and oil.

Maybe that’s why worldwide, new nuclear projects are not being cancelled – they’re multiplying. There are 110 projects currently under construction, and 112 more are currently planned, with funding secured and site commitments in place. In the next 15 years total nuclear capacity will increase by 44%. 30 countries are contemplating nuclear programs which never had them before.

Little of that capacity is planned to be added in Germany, the U.S., or a few other countries which share an irrational aversion to it (ironically, the two countries home to the two largest nuclear disasters, Russia and Japan, are both planning aggressive buildouts in coming decades). And just yesterday:

“Twenty-two nations, including the US, the UK, France and Japan, have signed a declaration at the COP28 climate conference to commit to tripling global nuclear energy capacity by midcentury to achieve carbon neutrality. The declaration recognizes the importance of financing for new builds and the role of the International Atomic Energy Agency in supporting the inclusion of nuclear in countries’ energy planning.”

https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Ministerial-declaration-puts-nuclear-at-heart-of-c

That the phrase “nuclear energy” appears nowhere in an article about a green transition, in 2023, is shameful. But since renewables have given the color a bad name, maybe it’s time for the U.S. to consider joining the global fission transition instead. It’s inevitable, and long overdue.

Definitely true that high interest rates hamper nuclear power even more than any other source. I did not focus on nuclear in my discussion of the US as active new builds do not look to be a major part of the picture, for better or worse.

The problem with nuclear power is not risk per se but cost. We’ve been continually been told how the next project with bring down the costs, but yet again we see doubling or tripling of the initial estimate. The demise of the Nuscale plant is just another example of a failed promise. Until the industry gets ahold of its cost problem, it’s going nowhere.

Why is it our government can build Nuclear Submarines, Nuclear Aircraft carriers even nuclear space craft but we can’t have Nuclear Power Houses.

I see this comment often, and just as often I wonder how true it is: “A 2% increase is nothing to sneeze at, but conventional estimates show that, even with elevated financing costs, renewables remain the cheapest source of power.” My suspicion is that renewables are the cheapest source of power on a project basis, but on a system basis they’re more expensive because of all the back-up power that needs to be built to compensate for when they’re not producing. I’d be interested in serious commentary on this issue.

I talked with several local rooftop solar installers recently. They said that single-family customers are transitioning to solar+storage but it’s only the cash segment that is doing so. Those that need financing (and even more important since a solar+storage system typically costs twice that of stand alone solar panels) have exited the market for the moment. They attribute that to the higher interest rates and the economic uncertainty that engenders. The chart from CALSSA in this story illustrates the slowdown in installs. https://www.canarymedia.com/articles/solar/californias-rooftop-solar-policy-is-killing-its-rooftop-solar-industry

Thanks for link highlighting how big the residential PV market has been affected by NEM 3. By chance have you had a chance to see if FERC’s recent paper/evaluation on “Reliability Standards to Address Inverter-Based Resources” (1) has

impacted the CASIO Day Ahead, 15 minute and real time markets? I noticed that there seemed to be huge differences in congestion costs at different locational nodes in PG&E service area yesterday.

1) E-1-RM22-12-000 | Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (ferc.gov)

https://www.ferc.gov/media/e-1-rm22-12-000

Mark Miller

Despite increasing since 2020, the costs of variable and intermittent renewables are still low. But so are the benefits. Solar produces when the daytime shadow price of power is lowest. Wind may be worse given the proportion of generation at night.

I’m guessing that levelized-cost calculations are based on the premise of “must dispatch.” But priority dispatch means that intermittent generation lowers the operating time of conventional generation. This lowers the return to utility shareholders and the return to new, conventional investments.

the uncertainty factor re resale values, and range anxiety, ie ‘risk’ is aggravated by the higher interest rates. i almost didnt get my VW ID4 because, between the time i placed the order in Sep 2021, and when the car was available in Jan 2023, the hike in interest rates had jacked up the lease payments from about $450pm to about $935pm. VW and state rebates brought the cap cost and monthly payment to a reasonable level.

Higher interest rates are, as many other actions, a wealth-transfer to the ‘already’ wealthy.

With respect .. Orsted’s cancellation had everything to do with The Jones Act and less to do with financing of the projects. Declaring otherwise isn’t an accurate assertion.

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/j/jonesact.asp

— A proposal to temporarily suspend Jones Act restrictions & train US crews aboard non-US ships while American made ships are being built was rejected. (Almost all the ships designed to service offshore wind are currently from abroad where that industry has already matured).

Orsted CEO Mads Nipper, on a call with analysts the day after announcing the recent cancellation of 2 east coast projects said: Significant delays on vessel availability in the entire US market are now implying a multi-year delay of the entire projects.

Steve Forbes talks about how the 100yr old Jones Act is effecting our economy as a whole:

Certainly there is more to the Orsted story. It wasn’t only interest rates, that’s true, but I would lump Orsted in with the broader set of things where interest rates are one potential factor.

Quite a sanguine summary. Wind’s cost of energy is up by 87% since Q1 2020, and solar is up 57% during the same period. The major long lead-time projects needed to decarbonize our grid, such as nuclear and seasonal duration storage, have had even larger increases due to having longer construction periods.

Only in a world where prices don’t matter because we can print unlimited amounts of money without negative consequences can one believe that our desired decarbonization journey is going to proceed uninterrupted.

High interest rates might make EVs more market-competitive. Within several years, EVs will reach “sticker price parity” in all markets, and lower operating costs help offset financing costs.

https://rmi.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2023/09/x_change_cars_report.pdf#page=12

Agree. We have to remember that just reaching parity won’t suddenly make all Americans flip to EVs. As such, every factor that makes them more appealing will probably drive a bit more adoption.

While higher interest rates slow most large purchases, when a needed automobile costs more to fix than replace, people tend to just replace it. The double whammy of NEM3.0 and higher interest rates makes home rooftop solar a bad investment since the utilities now keep 75% of the energy produced in California without compensation and the higher interest rates makes the purchase even more expensive. The choice of putting that Christmas bonus into 5% savings account or buying energy efficient appliances, when the old appliance is still working, and the only incentive is a federal tax credit, that may not help if there are no taxes due after exemptions or deductions, can also be a factor. Rebuilding one’s savings reserves, paying off existing debts could also be a factor in lower sales since most consumer debt is already at lofty heights at 28%.