In honor of Black History Month, we’re running a series of profiles and Q&As with members of the African-American community at Haas. Follow the series throughout February here.

In honor of Black History Month, we’re running a series of profiles and Q&As with members of the African-American community at Haas. Follow the series throughout February here.

We kick off our series with an interview with first-year MBA student Evan Wright, a Washington, D.C. native who is VP of diversity, equity, and inclusion for the MBA Association student government.

Berkeley Haas News: Tell us about where you grew up.

Washington, D.C., primarily in Southeast Washington, DC, which is a predominantly black and low-income part of the city. When I grew up in D.C., it was still a majority black city and the black community there was solidly middle class. I grew up in a famously progressive church, the People’s Congregational United Church of Christ, which had a strong social justice component. My pastor’s father-in-law was Andrew Young, who was famous for being a U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations and a part of the civil rights movement. I’m not very religious but I think growing up in that church where there were black lawyers, judges, black doctors, people living paycheck to paycheck, and manual laborers, I saw the full spectrum of what black people could be and how our lives could be anything—and I had a very strong social justice founding that very much influenced how I thought about myself as a black person.

What was your experience growing up black in your community?

Being low-income in D.C. meant that I had access to things that low-income black children in other cities didn’t have access to: free museums, summer programming, (former Mayor) Marion Barry’s program to give stipends for unpaid internships in the government allowed me to have government internships and get a bus and train pass to get to and from. Growing up in D.C. I had access to so much opportunity that I’m very thankful for. At the same time, I also grew up in D.C. in the 1990s during the war on drugs. I have had—and my family members have had—negative interactions with police from very early on. I had to very early on think about my physical safety coming to and from home in a way that other children I went to school with later on didn’t have to think about.

Was Black History Month a big part of your childhood?

Very much so. It was a very big event in my church. We would have people from leftist political movements, we’d do interfaith dialogues between the Jewish community and the Muslim community in the area. It was a very progressive education and we dove deep.

Who are some black historical leaders/writers who have impacted your life?

My favorite book my senior year was Revolutionary Suicide, written by Huey P. Newton, the famous leader of the Black Panthers. James Baldwin’s book The Fire Next Time was one of my favorites—just thoughtful in the way he can seamlessly talk about race, sexual identity, gender, and religion, and in all the ways that he interacts with being a black person in America.

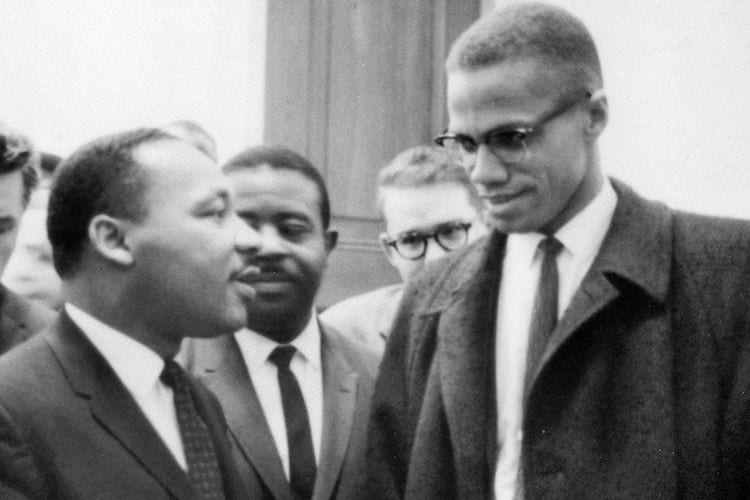

More than anyone else, I admire MLK and Malcolm X and I think both of them are much closer in ideology then they are seen to be in popular culture, where they are often whitewashed. Both of them were very critical of capitalist structures and arguably anti-capitalist, which I think is also something that people never talk about. Malcolm X had a quote that “you can’t have capitalism without racism” and King spoke and wrote about the “evils of racism, economic exploitation, and militarism.” King wasn’t a pacifist; he was a strategic, non-violent activist, which is very different.

What do you wish others knew about what it means to be black in the U.S.?

Growing up black in the United States is to constantly be told that you aren’t part of the group, that you’re somehow removed. You are told by the justice system, by the educational system, by all of these institutions that we hold up to be important, implicitly or explicitly, that you’re not an American, that you’re not a part of society. I don’t think that I could have expressed this idea until I went abroad to Singapore after graduation. I was there for a year and a half and I had Singaporeans come up to me and say, ‘Oh, where in Africa are you from?’ Their conception of what an American is is a white person, so I had to often say, ‘I’m African American. I’m an American.’ That was my first time having to assert my American identity.