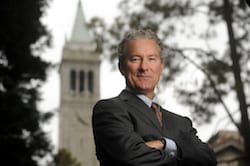

For urban development expert Victor Santiago Pineda, BS 03, no other legislation has altered the face of our nation as much as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

With the United Nations estimating that two-thirds of the global population will live in urban areas by 2050, cities like New York, Rio de Janeiro, and Dubai have sought Pineda’s input on how to redesign their physical and digital landscapes.

We spoke with Pineda, who also holds a master’s degree in city planning from UC Berkeley and a PhD in urban planning from UCLA, about the ADA, his lifelong mission to build cities for all, and what the Haas community can do to help. He directs UC Berkeley’s Inclusive Cities Lab and is the founder and president of World Enabled, a global education, communications, a strategic consulting firm.

As a leader in the disability community, how do you view the ADA’s legacy?

I stopped walking when I was seven years old, and by the time the ADA passed, I was using a ventilator to help me breathe. The ADA made sure that I was not “confined” to my wheelchair, but rather empowered by it. Beyond changes to our physical infrastructure, the law ushered in a paradigm shift in attitudes toward people with disabilities. This law also inspired over 180 countries around the world to follow our leadership. Today, we have a generation of leaders who expect the future to be accessible.

For companies, was that realization universal?

There are companies, like Microsoft, Accenture, and Google that recognized early on that the ADA is not something that hampers business, but rather transforms it. Others learned this the hard way. Netflix, for example, took its opposition to closed captions in its programming all the way to the Supreme Court and lost. Then, once they added captions, their sales went through the roof. Their shows became more accessible to more people. It’s a great example of how the ADA, instead of seeing it as a compliance issue, has been a source of innovation and a driver of growth.

Are laws enough to ensure cities are accessible?

To build cities and communities that are equitable, you need more than laws mandating wheelchair ramps. There is a broad spectrum of unmet needs inherent to the human condition, including aging and psycho-social disabilities, that have to be considered. Sixty percent of urban planning experts say that even the most innovative cities are failing persons with disabilities. Consider that 96% of ongoing digital development projects worldwide do not even mention people with disabilities.

How can this be addressed?

I have five criteria for making cities accessible. The first is about laws at every level of government and what they say about building accessibility into city services or the technologies that cities use. The second is about leadership: Are city leaders talking about these issues and using their budgets to identify barriers and remove them?

The third area, which is critical, is about institutional capacity. You need a cross-agency approach. For example, do all 56 agencies in New York City’s government understand what digital accessibility is? My fourth criterion is about participation and representation. Are you only talking to people who use wheelchairs about how to build an accessible smart city, or are you also asking people with dementia?

Finally, we need to change attitudes. We continue to have a divergent set of implicit biases around race, gender, and something called ‘ableism.’ We’ve inherited a public infrastructure that is ableist by design—meaning that, even with the ADA, it still gives preferences to people who can open doors, climb stairs, run around. Now, because of COVID-19, many more people are experiencing how it feels to have barriers and restrictions placed on how they access public spaces and services, so there is a greater appreciation for the challenges persons with disabilities have long experienced.

Your work on urban development is jaw-dropping in its scope. Let’s focus on your most recent initiative, Cities4All. What is it about?

The Cities4All Initiative is hosted at UC Berkeley’s Institute of Urban and Regional Development (IURD). We are building a global Knowledge Hub for Inclusive and Accessible Cities. The Knowledge Hub identifies and scales up best practices for transforming 100 cities worldwide to be more inclusive, accessible, and resilient by 2050. Our plan is to develop new data partnerships to monitor and evaluate inclusion in cities by creating a dashboard to better assess areas for improvement. Thirty cities, including Abu Dhabi, Helsinki, Berlin, Chicago, and Amman, have signed on to the campaign. Now they are asking for support in building capacity for their staff. They want training, tools, and technology, and we are partnering with business leaders from Haas and the World Economic Forum to deliver.

How can the Haas community support this work?

We’re asking the Haas community to question the status quo—to realize that, when it comes to people with disabilities, what we’re doing is not enough.

Alumni can join the Valuable 500 and put disability on their board agendas. They can ensure that disability forms part of their diversity and inclusion efforts. They can also support a crowdfunding campaign we will launch soon to raise $250,000 to support our Cities4All campaign.

The Defining Leadership Principle of Beyond Yourself reminds us that building more inclusive cities isn’t just about altruism. It’s in everyone’s self-interest, it’s about shaping the future.

As a Berkeley student, you were very active in student government and disability rights issues. What was your undergraduate experience at Haas like?

For me, Haas was an artistic enterprise. It was about the art of the possible and how bringing together engineers, managers, people in finance, strategy, and HR can unlock the capacity of a team to change the world through business.

I have also stayed in close contact with many classmates, including Eric Jones and Jared Dalgamouni, with whom I have had a friendly competition for the last 18 years. It was after we had won the Haas Social Business Plan competition in school and we were sitting in the library near a glass case that features prominent Haas alumni. We bet that whichever one of us gets featured in the glass case first gets a trip anywhere in the world and a glass of beer. Just the other day I told them about this interview and how it might get me one step closer to winning.

Berkeley Haas Dean Ann Harrison grew up with an insatiable curiosity and a dream to make the world a better place.

Berkeley Haas Dean Ann Harrison grew up with an insatiable curiosity and a dream to make the world a better place.

Over the next few years, as the cultural conversation around women at work gathered momentum, companies started asking McElhaney for more proof of a bottom-line payoff to hiring women.

Over the next few years, as the cultural conversation around women at work gathered momentum, companies started asking McElhaney for more proof of a bottom-line payoff to hiring women.

.jpg) “What’s interesting is that this isn’t an industry that came about because of some invention,” says Jessica Sun, MBA 17 (right), one of the two students who organized the course. “Cannabis has been around for centuries. It’s a social movement that’s now turning into an industry.”

“What’s interesting is that this isn’t an industry that came about because of some invention,” says Jessica Sun, MBA 17 (right), one of the two students who organized the course. “Cannabis has been around for centuries. It’s a social movement that’s now turning into an industry.” Katz didn’t have to look far to find students willing to run with the speaker series idea. Both Sun and Cody Little, also MBA 17 (left), had been drawn to Haas for its reputation as an incubator for business leaders committed to making a social impact. After meeting early last year, they began talking about ways they could further push the envelope on social justice issues at the school.

Katz didn’t have to look far to find students willing to run with the speaker series idea. Both Sun and Cody Little, also MBA 17 (left), had been drawn to Haas for its reputation as an incubator for business leaders committed to making a social impact. After meeting early last year, they began talking about ways they could further push the envelope on social justice issues at the school.