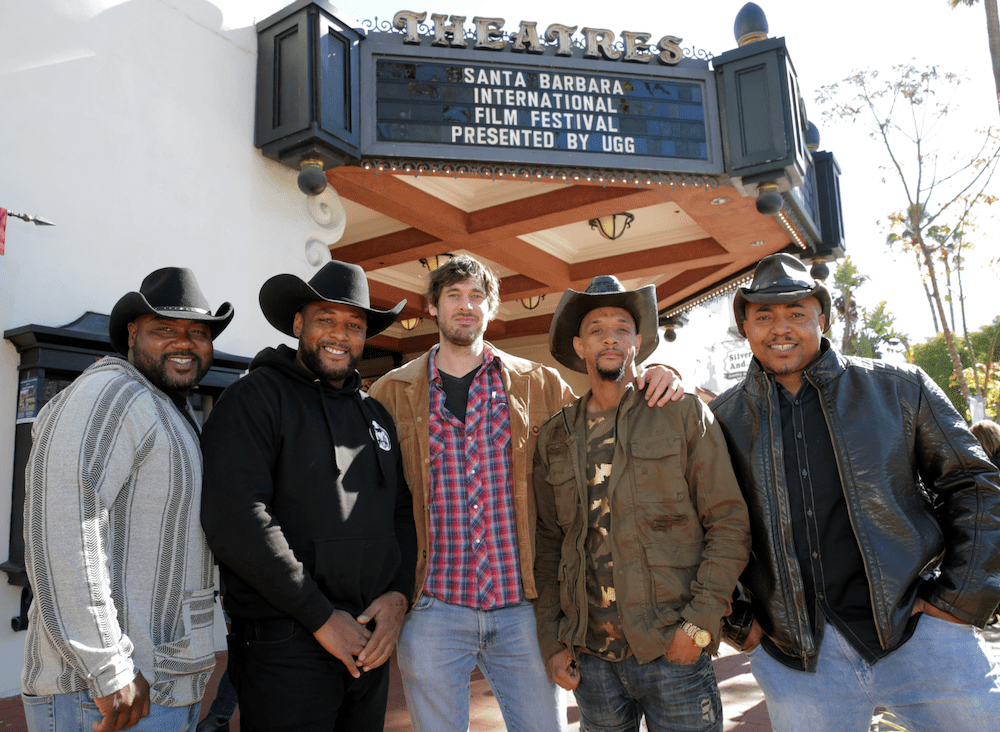

Brett Fallentine, BS 03 (business), and BA 03 (film studies), is releasing his documentary Fire on the Hill: The Cowboys of South Central LA on several streaming platforms this month, including Amazon Prime Video. The film centers on a group of urban cowboys and the last public horse stable in South Central, Los Angeles—and the aftermath of a mysterious fire that destroyed it. PBS will broadcast Fire on The Hill in June to celebrate the federal Juneteenth Holiday.

An award-winning documentary and commercial director, Fallentine started his film career as an apprentice editor to George Lucas on the film Star Wars, Revenge of the Sith. He now runs his own film company, Preamble Pictures. He is currently working on a new film about a family that defied all odds to survive the 2017 Tubbs Fire in Sonoma.

Haas News: So how did you find the story that became Fire on the Hill?

Brett Fallentine: I had heard about this riding community when I moved to LA, and I became really fascinated with it—the juxtaposition of this rural equestrian lifestyle in this neighborhood with rival gang culture located at the juncture of two major freeways in Los Angeles. It’s a place that you would never expect to see something like this happen but it’s this culture that’s been there since the1940s. A lot of famous riders have come out of this stable who’ve gone on to become world champions in rodeo, but no one really knew that at the time. Ultimately, that was one reason why I became so interested in the story.

So how did you find the Hill?

I went to places where people said they’d seen the riders before and no one showed up. Through several trips, I found manure and followed a trail that led to the Hill horse stable. I started interviewing and one interview led to another and another and they invited me on a ride. I wasn’t sure of the story at first, but after the Hill stable fire, I started learning about the history of the stable, the impact it had on the youth in the community, and why having this culture was important for them. I ended up meeting their families and watching them grow up over subsequent years of filming.

Did making this film shatter a lot of stereotypes for you?

One of the big themes that started to emerge was that positive stories like this one don’t really emerge from South Central because popular media tends to focus on the area’s violence and crime. I grew up in the 1990s when movies like Menace II Society and Boyz n the Hood popularized that area. So I believed that part of LA was dangerous and I avoided it. When I learned that this riding culture existed it sparked my curiosity enough to go down there and see for myself. I became interested in the story behind the Hill and the community of riders I met really changed my mind and my feelings about this area in a way that never would have happened otherwise.

Watch the trailer for Fire on the Hill.

You track multiple stories in the film, all different and compelling.

We follow Ghuan Featherstone, who worked with the youth in the community at the Hill. Among the rival gangs, the stable has always been a neutral zone that provides a way for kids to not only work with animals but to work with kids from other neighborhoods who they would not normally interact with. Since the fire, Ghuan has started a non-profit inspired by the Hill Stable called Urban Saddles. We follow Chris Byrd, a rising bull rider from Compton, who enters his rookie year of professional rodeo. There’s also Calvin Gray, who having found freedom on the back of a horse, must choose between the cowboy lifestyle and his family. Their stories shine a fresh light on what it means to be a modern “cowboy” in an urban world.

Their stories shine a fresh light on what it means to be a modern “cowboy” in an urban world.

How did Ghuan work with local youths? Were there challenges?

The kids in the neighborhood would wander into this stable, just mesmerized. They would first learn to care for the animals and eventually get to ride. But one of the quick lessons learned is that these animals are big and you can’t force them to do anything so you’re going to have to work with them. Ghuan told me about kids who learned to solve differences based on how tough they were. Soon they found out that you can’t really do that on a horse. You have to be willing to work with a horse and those insights started to carry over into how they were settling their differences back in their neighborhoods. That became an important message throughout the community.

How long did you work on this film?

I began filming in 2011 and the stable fire happened a few months into the process. The film took about five to six years after that to make because the subject’s stories were constantly evolving, even while we were in editorial. So I’d grab my camera and follow up on their stories. We completed the film in 2019, and showed it at festivals. Amazon Prime picked it up and released it in 2020, a time when the world was focused on Covid. So we’re thrilled to have it re-released on streaming channels like Amazon and have it nationally broadcast later this year through PBS.

We’re thrilled to have it re-released on streaming channels like Amazon and have it nationally broadcast later this year through PBS.

You said that you rode horses during the making of Fire on the Hill. Where did you learn to ride?

I did have some experience riding as a kid and riding was something that was always around me, but I had never really learned to ride until making this film. The cowboys provided a lot of opportunities to ride in South LA after the cameras had wrapped for the day. The men and women there were very open and willing to teach me and it’s become more of a part of my life now.

You entered UC Berkeley as a molecular and cellular biology major. How did you land in film?

I switched majors my sophomore year, which is pretty late in the game, especially going from science into the arts and business. I had always been behind a camera as a kid, making little movies and commercials growing up, but my family was science-focused, so that was the assumed route. I was in class in a lab one day and there was kind of an epiphany where I was like, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ and at that moment I switched from being an MCB student to double majoring in Film Studies and business at Haas.

How do the two degrees work together in your career?

They work hand in hand. I started working on Star Wars, Revenge of the Sith during my last semester at Berkeley, and I was using a lot more of what I’d learned at Haas than I was with the film studies. Over the years, I’ve found myself going back to what I learned in marketing, accounting and organizational behavior. Film is a business and having that knowledge has been super important to me.