With more than 150 million users in more than 190 countries since its founding in 2008, nonprofit Khan Academy has become an educational staple for students and instructors alike.

Khan Academy CEO and Founder Sal Khan traced his journey to provide free and accessible online education during the first fall Dean’s Speaker Series talk Sept. 19.

After graduating from Harvard Business School in 2003, Khan worked as a hedge fund analyst, having told his friends “I’m going to do this long enough so that I could become independently wealthy.” Around the same time—having always been passionate about education—he began tutoring his cousin over the phone using an interactive notepad. From there, Khan expanded his lessons to include family and friends, even writing software to create deep item banks—databases of questions—to help them practice.

With advice from a friend, he began incorporating video, uploading his lessons to YouTube—and by 2008, Khan Academy reached almost 100,000 users. Even with the nonprofit’s initial traction, however, Khan noted the risks that come with starting any new business.

“I think anytime you do anything entrepreneurial—for-profit or nonprofit—you have to start with that delusional optimism. You assume that surely the market, the investors, the philanthropists, whatever, whoever the stakeholders are, they’re going to recognize the value of what you’re creating. And oftentimes, it doesn’t happen as fast as you think,” Khan said.

I think anytime you do anything entrepreneurial—for-profit or nonprofit—you have to start with that delusional optimism.

Despite receiving offers from venture capitalists, Khan turned them down to maintain control and ensure his organization remained free and accessible. Nine months later, current Khan Academy Board Chair Ann Doerr made an initial donation, which led to a lunch meeting and eventual working relationship.

After Bill Gates talked about his own kids using the platform at the 2010 Aspen Ideas Festival, Khan had another meeting to discuss ways to support Khan Academy’s future. This, coupled with more funding from Google, allowed Khan Academy “to become a real organization,” Khan said.

Since then, Khan Academy has expanded to include more than 70,000 practice problems with translations into more than 50 languages. The nonprofit is also partnered with upward of 500 school districts, even having its own accredited schools: Khan Lab School in Silicon Valley and Khan World School, a partnership with Arizona State University. Now, Khan Academy is launching Khanmigo, an AI educational chatbot, to help instructors and students understand how to use AI to support learning.

In terms of running and scaling a nonprofit with an impact like Khan Academy, Khan cited the importance of teams maintaining a clear mission.

If you can grow and maintain your talent and your alignment, a 300-person team can outperform a 30,000-person team.

“The hardest thing is, as you grow, to maintain alignment. If you can grow and maintain your talent and your alignment, a 300-person team can outperform a 30,000-person team,” Khan explained. “Alignment is not just communication. And this is a muscle that I don’t think people in Silicon Valley exercise enough—being very clear with team members: ‘Look, this is what we’re doing. If you’re excited about that, awesome. If you’re not, this might not be the place for you.’ That is kind of strong language, but I have found it to be very powerful language because otherwise people are just trying to pull (the organization) in all sorts of different directions.”

Watch the full DSS talk below.

Read the full transcript:

– Good afternoon, welcome. I’m Don Moore, acting dean here at the Haas School of Business. I’m thrilled to welcome all of you to the first Dean Speaker Series of the year. Today’s guest, as you know, is Sal Khan, founder and CEO of Khan Academy. Sal holds two bachelor’s degrees of science and a master’s in electrical engineering from MIT and an MBA from a school called Harvard Business School, which you may have heard of. Sal became passionate about education while he was an undergraduate at MIT. He developed math software for children with ADHD and tutored fourth- and seventh-grade public school students. While working as a hedge fund analyst in 2004, Sal began tutoring his young cousin in math over the telephone with an interactive notepad. Within a couple years, he added more than a dozen relatives and family friends to his online classes. In 2008, he founded Khan Academy with a mission to provide free, world-class education for anyone, anywhere. Khan Academy now partners with more than 500 school districts and schools across the United States to help teachers tailor instruction to each student. Khan Academy is now used in more than 190 countries. There are more than 150 million registered users around the world and translations into more than 50 languages. Today, Khan Academy’s platforms include more than 70,000 interactive practice problems, as well as videos and articles that cover a range of subjects from pre-K to 12th grade. Khan Academy is piloting a new tool called Khanmigo, which gives students an entirely new way to use AI to learn. He also wrote a book, The One World Schoolhouse where he presents his radical vision for the future of education with a goal of leveling the playing field for access for all to world-class education. Thanks, Sal, for taking the time to join us today and to talk with us about your work. Now I’ll turn it over to today’s moderators, MBA students Anu Tej and Mrudula Vemuri.

– Thank you for that introduction. I’d like to just introduce myself one more time. My name is Mrudula Vemuri. I’m an EWMBA class of 2024. And I’d also love to share my first story using Khan Academy. I was desperately in need of help with my calc homework, and I had a calc final looming in college, and I turned to Khan Academy, and it hasn’t failed me ever since. Even through my macro and finance courses here at Haas School of Business, I’ve used Khan Academy, and it’s helped me all along the way, so I can’t wait to see what they have in the future.

– OK, I am Anu and I’m a full-time MBA class of 2024. I first learned about Khan Academy just after my undergrad. I had joined this early stage startup, and I was given a task to do data analysis, and I had no idea how to do it, and one of my teammates came to me and said, “Oh, you might want to check out Khan Academy for some of the concepts.” And I started with high school statistics that night, and I was like, “Oh my God, I needed this in college. I needed this in high school.” All this while I thought I suck at statistics, I did not. I was able to do that analysis that I did; and like Mrudula, I was able to pass my macro economics last year because of Khan Academy. Thank you so much for helping us. So I want to start,

– [Sal] Always good to hear the stories.

– I want to start with the origin story, Sal. I know you were tutoring students during your high school, and I also know that you will tell your friends when you are working in a hedge fund that ‘I want to work in hedge fund long enough to start my own school someday.’ So tell us more.

– Yeah, first of all, thanks for having me here, and as I said, always great to hear y’all’s stories. Yeah, I’ve always had this interest in education. I think going back to maybe even elementary school where we all had good moments in our education experience; and then we all had some not-so-good moments. And usually, some of those not-so-good moments are feeling a little bit bored or feeling disengaged or seeing some of your friends bored or disengaged. And so I’ve always been fascinated that there’s got to be a better way to do this. Anyway, you fast-forward to, I graduated from undergrad. My first career was in tech. Then after that, I go to business school. After business school, I find myself, I’m at a small hedge fund in Boston at the time, and I graduated from business school in 2003, and it’s now 2004. I had just gotten married. My family was visiting me up from New Orleans, which is where I was born and raised up in Boston. And even before that, actually, to answer your question directly, when I was working at the hedge fund—and this is what I did tell myself—but I would tell my friends who were like, “Well, what’s your lifelong goal?” I was like, “Well, I’m going to do this long enough so that I could become independently wealthy,” which I have not achieved, but I did the other, well, the thing I wanted to do after I wanted to be independently wealthy, so I can start a school on my own terms. I thought that would be the most fun thing to do, to be one day, be like a Dumbledore-type figure, but once again, in some ways have to convince anyone that, and we could talk more about, there’s some benefits of having to convince people things. But when it became clear that my cousin Nadia needed help, she didn’t even know that she needed help, but I knew that she needed help. She was in seventh grade, and she was put into a slower math track, which had all sorts of potential negative implications for her future. I offered to tutor her remotely when she went back to New Orleans. She agreed. And so, yeah, we got on the phone. We used to use instant messenger at the time to just communicate. We could see each other’s writing, et cetera. Slowly but surely, she got caught up with her class, even ahead of her class. At that point, I become what I call a tiger cousin. I called up her school, I said, “I really think Nadia Raman should be able to retake that placement exam from last year.” They said, “Who are you?” “I’m her cousin.” And they let her take it. And the same Nadia who was being tracked into a remedial track was now put into the advanced track.

So I was hooked. I started tutoring her younger brothers, Armand and Ali, and it was working with them, and word spreads in my family, free tutoring is going on. So before I know it, there’s 10, 15 cousins, family friends that I’m tutoring on a regular basis. My day job, I was at the hedge fund, but markets close. I’d get on conference calls with, for the most part, my cousins, a few family friends.

But that’s how I started, and I was enjoying it. I was connecting with family, but I was also, I believed that there’s a way of approaching a lot of this subject matter that could be very intuitive and even enjoyable for my family. I also saw that there was a common pattern, and I saw this pattern throughout my education. The reason why folks struggle isn’t because they aren’t bright. It isn’t because they don’t have good teachers or they’re not hardworking. It’s usually because they have gaps in their knowledge. And by the time you get to an algebra class, it’s really hard to address those gaps of, say, dividing decimals or negative numbers. And those gaps happen in a traditional system because kids just keep getting moved ahead, even if they get a 60 or 70 or 80%, or they forget stuff. So that’s when I started writing some software for my cousins, too, ’cause I honestly couldn’t find any good practice on the internet at the time. This was back in 2004, 2005. Because I wanted them to get as much practice as they need. So I was creating these very deep item banks that were partially computer generated, et cetera. And that was the first Khan Academy. It had nothing to do with videos at the time.

Then in 2006, by this point, we had moved out to the Bay Area. I was at a dinner party showing off the software. I’m a super cool dinner party guest, and the host of the dinner party, his name’s Zuli, I have to give him full credit. He said, “Well, this is cool, Sal, but how are you scaling your lessons?” And I said, “Yeah, it’s hard to do with 15 cousins what I was originally doing with just a handful.” And he said, “Well, why don’t you make some videos, upload them onto YouTube for your family?” I told him, “That’s a horrible idea. YouTube is for cats playing piano. It’s not for serious math.” But I got over the idea that it was not mine. And I gave that a shot. And that took on a life of its own, obviously. My cousins famously told me they liked me better on YouTube than in person. I think what they were saying was that they enjoyed having an on demand, not feeling shy, not feeling embarrassed. If it’s 11 p.m. and they had a question, they could access it. I believe they still enjoyed being able to get on the phone with me to go a little bit deeper. But then a lot of other people started discovering it. And then by 2008, there were about 50 to 100,000 folks using it on a monthly basis. And that’s where I incorporated it as a not-for-profit, a mission-free, world-class education for anyone anywhere. 2009, I frankly had trouble focusing on my day job. We had some savings at this point. My wife was a medical fellow, so she was still in training. Our first child had just been born, so our expenses were going up, but we were saving some money for a down payment out here in the Bay Area, which we all know is not a joke, even back in 2009. But we felt, well, maybe if we give it a year, hopefully someone will fund this philanthropically. So that’s when I took the plunge, and that first year wasn’t easy, but eventually, it worked out.

– Well, thank you. I know that I have personally shamelessly rewinded many, many videos. In my personal experience interacting with Khan Academy, I noticed that there’s a huge breadth of topics. Were you familiar with all of these topics before the beginning of Khan Academy? And if not, how did you teach yourself so many different things?

– Great question. The simple answer is no. I think that there, with that said, well, I can surprise folks with my breadth. Let me just say that I’m definitely above average. But there’s certain topics that I did know very, very well, math being one of them. I would say math and physics and some other parts of science I knew very, very well where I could kind of get into it. I didn’t need necessarily a reference or a textbook.

With that said, once Khan Academy became a more professionalized organization and we wanted to make sure we covered all of the standards, we now have a team who’s curating the questions and figuring out the scope and sequence and instead telling me, “Hey, they’re using a different term nowadays for,” I mean, the most famous example is when I was in school, it was called atomic weight. Now it’s average atomic mass. Or let’s redo a video. So there’s definitely support now, but in those early days, but even now, I take joy; and maybe there’s folks in this room who feel the same way that if you learn to learn something well, that that is actually a very transferable skill to almost anything. And it goes against what I think most people are indoctrinated into in school. My biggest pet peeve is when I hear someone say, “I’m a math person,” or “I’m a humanities person.” And unfortunately, you’ll sometimes hear it from educators. In fact, you’ll almost always hear it from, you want to give a math teacher anxiety, ask them to engage in the humanities, or you want to give humanities teacher anxiety, ask them to engage in math. And even at a high school level, like, you graduated from high school, right? Like, this shouldn’t be something… So unfortunately, I think sometimes that not optimal signaling happens to students.

But I think generally speaking, if you learn to understand something really well in any domain and you build that muscle of, like, asking the right questions: Wait, how does A lead to B? I’m not just going to take it as a leap of faith. I need to understand it, prove it to me. How does this make intuitive sense? You can take that to almost any domain. And I’ve always been, some of the subjects in Khan Academy are things like history, and I’ve always really been fascinated by history. I don’t have any formal training in it, but I’ve been fascinated both on just, like, these are real human stories that happened. How can it not be interesting? But then also I’ve always been sometimes frustrated on not being able to place things in time and space and seeing timelines and things like that. So I’ve tried to take that tack and when we try to cover some of that on Khan Academy, and we’ve gotten positive feedback. And then there’s certain even science topics that, when I took it in college, I took organic chemistry in college. It was not a class where I was like, “Oh, this makes intuitive sense.” I got through the class, I got a fine grade, I did what I needed to do, but I didn’t get out of that class thinking like, “Oh, I see the beauty in organic chemistry.” So when it was almost, as a challenge, some of those organic chemistry videos are still up there on Khan Academy. When I did this almost 10 years ago, I said, “Before I even press record on that first video, I’m going to just sit and immerse myself in organic chemistry for several weeks until I learn to love it, until I learned there must be an intuition behind it.” And there is and actually, it all boils down to electronegativity, actually. You don’t have to memorize as many mechanisms as you think. And I would call up friends and stuff like, “Explain this to me. Why is this happening?” And someone would say, “No, we don’t know. That’s an area of research.” I was like, “Well, someone should tell the students that too, so they don’t bang their head on a table and they’re like, I’m actually trying to figure out an area of open research.” So yeah, I don’t know it all, for sure. And I do use Khan Academy when I’ve already made 80 videos in a certain course and they want an 81st. I sometimes have to watch some of the videos that I already made in order to get up to speed.

– Oh my God, thank you so much for that. Can you tell us, I mean, you briefly took us through from your undergrad, to, like, starting of Khan Academy for your cousins and, like, the whole journey ’till today? But can you tell us what would you consider your first big break in your life? This can be before Khan Academy or after.

– Oh, big break. Oh, so many breaks. I’ll give you more than one. Probably the first is when I was in second grade, my older sister was three years older than me, and she was, like, the star student. She was in the gifted program. I thought I was in the gifted program because they take you out; they took me out of class every day into some kind of enrichment thing. It turned out it was speech therapy. So I was being in a different, I was put in a different category than my sister, but because I was Farah’s younger brother, I think the school said there must be something there. And so they kept testing me. And so the first break was I went from speech therapy into this kind of gifted enrichment program that they had. It was Louisiana Public Schools, not famous, but it was a really good program. I still remember that first day, 7 years old, I walked into a classroom, unlike any other classroom I had ever seen, there were just, like, five or six kids in the room. Some kids were playing chess, some kids were drawing, some kids were playing “Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?” And there were two teachers. I mean, it was well-resourced if you really think about it in hindsight. And they’re like, “Oh, Sal, come on in.” And I walked up to both the teacher’s desks and they said, “Oh yeah, so what are you into?” And I said, “Well, I really like drawing. I really like puzzles.” And so they’re like, “OK, so we’ll draw and do puzzles.” And I didn’t even want to tell anyone about this thing ’cause I thought it was some type of, like, secret racket going on inside of my school that would be taken away from me if people knew what it was. But that I consider a break because one, that opened my eyes to what school could look like if everyone was really engaged and interested. And I think most of my memories from elementary school are that, so it had a real impact on me.

I mean, there’s a bunch of other breaks. I would say another, I’ll give my sister credit. When I was in, we didn’t have a lot of money, raised by a single mother. My mom was essentially making minimum wage eventually. And I remember when my sister was applying to college and I asked her, “What’s your first choice?” She said, “Brown University.” And I said, “You’re nuts. Brown University’s tuition is twice what our mom makes per year. Like, there’s no way that you’re going to Brown University.” And then my sister explained to me about financial aid and this and that. And my sister got in and was able to go. I mean, she still had some significant debt, and I think it’s gotten more generous since then, but it was very generous. It’s much better than what we thought it would be. So, that I considered a break of sorts ’cause that opened up my aperture to what’s possible.

You fast-forward, I mean, I’ll give a couple, well, I’ll fast-forward to the Khan Academy ’cause I think there was a big break there, which is, I talk about quitting my job. Me and my family are now living off of savings. I think anytime you do anything entrepreneurial for-profit or nonprofit, you have to start with that delusional optimism. You assume that surely the market, the investors, the philanthropists, whatever, whoever the stakeholders are, they’re going to recognize the value of what you’re creating. And oftentimes, it doesn’t happen as fast as you think. When I quit my day job, I was talking to some philanthropists, but very quickly, those pitted out. They really didn’t know what to make, how to make sense of what we’re trying to do at Khan Academy. And about nine months into that, it was stressful. I was waking up in the middle of the night. We were digging into our savings, about $5,000 a month. It was quickly not a down payment on a house anymore. And I was really questioning every, I’d given up a good career that I, for the most part, enjoyed. And then it was, yeah, about nine months in, all of a sudden, a $10,000 donation came in. I immediately emailed the person, her name is Ann Doerr. She’s now our chairperson. But at the time, I said, “Dear Ann, thank you so much for this incredibly generous donation. This is the largest donation Khan Academy has ever received. If we were a physical school, you would now have a building named after you.” And Ann responded back and said, “Well, that’s surprising to me. It’s actually surprising to me you’re a one person operation. I thought this was, like, a real thing. I see you’re in Mountain View. I’m in Palo Alto. I’d love to have lunch and learn more about what you’re doing.” So we have lunch, and Ann kind of asked me, “What’s your goal?” I said, “Look, I filled out free, world-class education for anyone anywhere.” And says, “Well, that’s ambitious. How do you see yourself doing that?” And I said, “Well, I’m building out all these exercises, videos, I’m going to go into all subjects, all grades, all and all this practice software to allow kids to learn at their own time and pace. I had already started building some teacher tools so the teachers could keep track of it. I had a notebook of testimonials from around the planet.” I said, “Eventually I want to localize this into languages of the world.” And Ann said, “Well, that’s ambitious, but how are you supporting yourself?” And I told her in as proud of a way as possible, I said, “I’m not.” And she kind of processes that. She pays the bill, and then we part ways. And about 10 minutes later, I’m driving into my driveway in Mountain View and I get a text message from Ann and it says, “You really need to be supporting yourself. I’ve just wired you a hundred thousand dollars.” So that was a good day a little bit. So that was great…

I’ll list one more ’cause the story only gets crazier. About two months after that, this is now about May of 2010, I want to say, or maybe June. I’m running a summer camp ’cause I never thought online is a replacement for physical. I always thought online could be a liberation of the physical, so you could do more games and simulations and things like that. So I was literally running a trading floor of seventh graders, and I start getting text messages from Ann, which you can imagine I now take very seriously. And there were five or six text messages that were coming. It was a little bit disjointed, but Ann was essentially writing, this is Ann writing, “I’m at the Aspen Ideas Festival. I’m in the main pavilion. Bill Gates on stage last five minutes talking about Khan Academy.” So I didn’t know what to make of this. And y’all can look, if you do a web search for like Bill Gates, Aspen Institute, Khan Academy 2010, you should find this video. But I found this video when I boot, I booted a seventh grader computer, and I found a delayed broadcast or a recording of it where Walter Isaacson asked Bill Gates, “What are you excited about?” Open question. And Bill Gates just, “There’s this guy Sal Khan. He’s got this website, Khan Academy. I use it with my kids. I use it myself.” And I was like, “Is this really happening?” And I remember that night I showed my wife that. I’m like, “What do I do now? Do I call him up? Like, what’s the protocol here?” And they left me in that state for about two weeks. Two weeks, I’m in actually this walk-in closet where I still am about to, worldwide headquarters of Khan Academy, about to record a video. And my cell phone rings, it’s a Seattle number, and I answer it. “Hello?” “Hi, this is Larry Cohen. I’m Bill Gates’ chief of staff. You might’ve heard that Bill’s a fan.” “Yeah, I heard that.” “And if you’re free in the next few weeks, we’d love to fly you up to Seattle and figure out ways that we might be able to collaborate.” And I was looking at my calendar for the month, completely blank. So I said, “Yeah, sure. I got to cut my nails next Wednesday, but I’m happy to meet with Bill.” But anyway, we had that meeting, and it was very similar to the meeting with Ann. And so by fall of 2010, and actually I was having similar meetings at around the exact same time with executives from Google, and I can talk more about that, who were trying to fund a, they were going to fund five projects that could change the world was their charter. And then fall of 2010, it all converged. So that was a major break. The Gates Foundation and Google, on top of the money the donors gave, allowed us to become a real organization.

– Wow, thank you for sharing all of those big breaks. And I hope that a lot of us in this room are hoping for our next one. Just to go back a little bit further down memory lane, who was a favorite teacher in your past and how would their role be transformed by Khan Academy and generative AI and ChatGPT that’s coming into the world now?

– Oh, good question. I’ve answered the favorite teacher, but not the combo one. I’ll give credit to, I talked about that first day in second grade, Ms. Kraus and Mr. Cell in that enrichment class. I think what would’ve happened if Khan Academy existed then, some of that “Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego” play would’ve been Khan Academy play. And you would’ve had some kids in Metairie, Louisiana, accelerating dramatically in math and science and other subjects.

Ms. Ellis was my fifth-grade social studies teacher. And I remember her because in hindsight I realized how brilliant she was. She ran her fifth-grade class like a humanity, a college graduate seminar. I remember she used to just peel an orange at the front of the classroom and just ask us questions all day about like, “So why do you think they did this? And why do you think this happens? And what would’ve had been different if they didn’t decide to declare war and et cetera, et cetera.” And I always found it really interesting, and later, I realized how special it is to have a teacher like that. If Khan Academy, Khanmigo and all of this existed, yeah, I think it would’ve provided even more space for that type of Socratic dialogue because students could get a lot of the core skills at their own time and pace. And if you have the AI to also be able to supplement and you can ask some questions that you might otherwise be embarrassed to ask in class, all the better.

Let’s see, I remember Ms. North was a really cool teacher in middle school who once again liked a very Socratic, very philosophical type of question. She was our English teacher.

And then in high school, Mr. Hernandez, who was a math teacher, but he was also the advisor. It might not surprise you, I was the president of the math club, and he was our advisor, and he kind of treated me as a colleague, which was really great. Like, we would plan things together. And I really appreciated that.

And then Ms. Kennedy, who ran journalism. She also ran it, like, we would just run, she ran it like a company, like, we ran the newspaper and she was like the chairman and she would advise us and help us.

And I should also, when I was in high school, I did dual enrollment at the University of New Orleans, and there was a professor there, Dr. Santania, who when he realized that I was taking some very advanced math courses with him. And when he realized that I didn’t have a computer at home, nor could I afford one, he got me a job at the university doing research with him. And that’s essentially how I first got access to a computer and I started learning how to program, et cetera. So yeah, I don’t think—I might not be here if any of those folks maybe weren’t there.

– Wow, thank you for sharing those inspirational stories and how those people have impacted your life. I know that you’ve told us that learning the ability to learn is of utmost importance, but what’s a skill that took a lot of time or attempts to master for you?

– Oh, that’s a good question. I mean, if I go refer back to what I’ve already told you, learning to speak properly. I still have to pause before I say hospital ’cause until I was about 8 years old, I would say hostable. And I still sometimes will if I’m not really, really careful. So I always say hospital, I pause. So I’ll say that.

Other things, well, I’ll say at the other end of my life, and this is one that unfortunately a lot of folks I think haven’t invested enough in is, in 2015, so eight years ago, like, weird things were happening. Like, I started getting claustrophobic on planes. Like, I would get on a plane, and I’d, like, want to get out as soon as possible. Like, it was not a pleasant experience. And I’m, like, something’s off, and I wasn’t sleeping well. And in hindsight it was really; I was probably too stressed, and t’s like a frog in boiling water. It just creeps up slowly, and it manifests itself in these really weird ways. But I started taking meditation very seriously at that point, really just so that, ’cause I had to travel, and I, just to see if it would make the planes more pleasant. But that practice of meditation I now take very, very, very seriously. And a lot of times, especially people who are ambitious, who want to do big things in the world, they try to kind of account for their own time as much as possible. And they try to be as on and as productive. And I still do that. I try to be as productive as I can when I’m on, but the off time is just as important, arguably more important. And I think it’s easy to overlook. So it’s taken me—it took me, when was that? I was 39 years old when that happened. It took me 39 years to realize that. And I think every year, I realized that more and more and every year, I take more permission with myself to, “I’m going to go to the sauna today,” or “I’m going to take this meeting walking around the park,” or “you know what, I’m just going to cancel these three meetings ’cause I don’t think I really need to be in that. And instead I’m just going to go meditate outside.” And I actually think that makes me more productive and it makes me a better entrepreneur, leader, whatever you want to call it.

– Wow, I think especially MBAs needed to hear that. We definitely need some off time and definitely some meditation to help us feel grounded. I did that just again before getting on stage. And maybe you answered this, but I’m going to ask this again. What is a topic or a skill that you think everyone should learn that is traditionally left out of K-12 education?

– Oh, so much. I mean, look, I’m talking to a bunch of MBAs. A lot of what I learned in the first year of business school, like accounting and the core of finance and how do you price something and present value? The mathematics of it are, like, middle school mathematics. It’s not super difficult. I don’t see any reason why that shouldn’t be taught in middle school or worst case, in high school. Anyone who just needs to think about one day starting a business or trying to decide whether they’re going to rent versus buy a house, they should learn that.

So I would say those types of skills and at minimum, personal finance skills, and this is something that schools are increasingly, at least states are passing legislation for schools to teach it. I think the schools without help are going to have difficulty ’cause like who’s going to teach it? Well, we’ve been working on this for many years, but we’ve recently launched a full financial literacy course. It’s targeted at the high school level, but honestly it’s useful for anybody where it’s like, people, well, I remember, I had an MBA and the first time I went to buy a house, I was just like, “Why do I need title insurance? What is title insurance?” You’re like, “What is this thing? And exactly how does escrow work, right?” So I think that type of thing is super, super useful.

There I had a brief period in undergrad where I wanted to be a, well, I’ll say there’s a class I took actually in, I was going to talk about, I briefly thought I wanted to be a lawyer, but then there was a class I took in business school called business law. But it was essentially, it was a crash course in law. And I remember thinking, “This could have been taught to me when I was in seventh or eighth grade.” Like, it should have been taught to me in seventh. Most people get through the whole education, including a college degree or including graduate school, and they don’t understand the legal system, which seems pretty darn important. So yeah, I would throw in financial literacy, legal system, basic finance, and accounting. Those are the big ones.

– Thank you. So our next question is: You’ve started Khan Academy and registered it as a nonprofit organization, and you’ve continued to run it as a nonprofit. How did you decide on this business model, and why not a private company?

– Hmm, yes. And there’s actually I think now three business school cases on this decision. How it’s evolved, it’s interesting. My day job at the time, I was a hedge fund analyst, which was arguably the most for-profit activity. It was only for-profit. Like, there’s no other benefit, or well, liquid capital markets and pricing efficiency, every hedge fund on the margin is helpful. But anyway, it’s primarily for-profit. But while in that job, I was able to be a really, it was interesting to be an observer of how organizations’ behavior was driven by capital structure. That honestly, you had annoying people like me, hedge fund analysts calling you and trying to figure out whether you’re going to meet or miss your earnings this coming quarter. And usually, the way that executives are compensated at these firms are based on stock performance and things like that. And I also saw when the debt holders are senior versus to when you have a strong founder versus when you’re in the second generation and the founder’s left, very few of these organizations are able to stay. There are for-profit organizations that start with a strong, mission-driven founder and are able to stay true to that until something happens to the founder or until the founder doesn’t have control of the organization anymore, right? Private equity just bought it or well, now the founder owns 20%, but 80%, it’s a public company now, or the founder dies, goes away, gets fired, and now someone else is taking over. There’s very few examples you can give.

And there is an irony that the only class in business school—I don’t know about Haas—but where I went to business school, they didn’t fail anybody, but they would give you these like internal grades and the only grade that I would’ve been, like, the equivalent of a fail if they actually failed anyone, was a class called social entrepreneurship. Because I was so skeptical of some of these nonprofits, I was just like, “Yeah, they tell a good story, they pull on your heartstrings, but is that really going to cure cancer? Is that really going to blah, blah, blah, blah.” And that’s what I wrote in the essay until I realized that that was the not-for-profit that the professor started, but not a good idea. But it didn’t fail anyone, so not a big deal either. It allowed me to speak my truth.

So I was cynical, but being in the hedge fund world, I said, “I want this Khan Academy project to just always be there.” I read a lot of science fiction. I was like, “what if this could be like a new type of institution, like the next Oxford or Smithsonian, but it could be on a completely different scale. It could be for billions one day and maybe it could last for hundreds of years.” And if you look at that, the only organizations that can be true to that type of a mission are not-for-profit organizations. And so, it’s sometimes delusional to say that you want to be the next Google or the next Facebook or the next Amazon. That’s hard enough. It’s arguably even a little bit more delusional to say that you want to be the next Oxford or you want to be the next thousand-year institution, but you live once, why not try?

– And what are some of the biggest challenges you faced while running and scaling a nonprofit organization? I know it’s very unique and different from running a for-profit company. A lot of our classmates who are in this room today are either building their own organizations like this or want to join one and lead one of these organizations.

– Yeah, if you asked me in 2000, if you asked me in late 2009, I would’ve said the biggest challenge is raising money and convincing people that you’re legitimate. I, at the time, took the most naive strategies and look, the advantage that Khan Academy had or that I had was that I was making something that was discoverable by people. I think it’s a very different thing if you’re starting a not-for-profit where you’re taking donations from one group and then you’re going someplace in the world and then you’re putting that money, I’m probably not the best person to ask on how do you start a not-for-profit like that. But here, not only was I making something that people could find and discover, but it was happening, it was growing, in those early days it was growing 15, 20% per month. So it was on this kind of exponential growth curve that people would associate with a high-growth tech company. And look, VCs were coming up to me and they were saying, “Hey, I’ll write a hundred thousand dollars check right now. You can quit your day job.” And it was tempting and I would take the second meeting with them, but the second meeting, they started talking about premium offerings and putting this behind a paywall and that and this is how you’re going to, and I’m like, no, and I was getting letters from kids that I knew and families that I knew would not be able to use the tool if this VC had their way. And so that’s why I kept turning that down, and luckily, my naive strategy kind of worked with people like Ann discovering it. And eventually, I mean, you can’t plan for Bill Gates just showing. I have a theory that I sometimes play with that benevolent aliens are using Khan Academy to prepare humanity for first contact. And some of what I told you of like, these things that seem a little bit more than just chance. Those are my data points. I have more. I actually think the benevolent aliens help set me up with my wife as well, so that I can prepare humanity for first contact through Khan Academy. But I have some good stories there.

But the real difficulties, I think, beyond that first validation, which is a hard one, and it was really hard. I mean, I kind of laugh about that nine months where I really didn’t know what I felt like; I kind of ruined our financial future. But once we started to have resources, I think it is, and we were a little bit, we are still unusual. We’ve been able to attract very good talent. Like, the main arguable advantages that a for-profit has over a nonprofit is access to capital, access to talent and potentially some notion of the incentives make you act in a different way, which could be good or bad. Access to capital, at least in those, in hindsight, I’m happy that the access to capital we’ve had, our budget is a real budget where it’s like 60, $70 million a year now. And it’s primarily philanthropic. So we have been able to do that.

Now, there have been other for-profit organizations, including in EdTech, that started a year or two after Khan Academy; and they get higher and higher valuations, and they’re able to do these really huge rounds and raise a hundred million, raise 500 million, raise a billion dollars. And as a 30-year-old, I would’ve been somewhat envious of that. Now, I don’t envy that at all because that creates all sorts of distortions and pressures. And the hardest thing is, as you grow, to maintain alignment. If you can grow and maintain your talent and your alignment, a 300-person team can outperform a 30,000-person team. I’m not saying this even as an exaggeration. I 100% believe this. Like, you see this playing out in the real world right now. I mean, OpenAI is a 300-person team. I think they’re outperforming many 80-, 90,000-person teams on what they’re doing ’cause they are aligned. And to some degree, probably the scarcity of capital in their early days helped drive that. And their group that I know very intimately now, and I know some of the 90,000-person organization, some of them were our original funders very well as well. But yeah, I think that alignment, when you get to like 20 people, you start realizing that people just don’t always assume the obvious, what you think is the obvious thing ’cause you’re not just having conversations on the way to the snack counter or whatever. And so you have these growing pains. There are like 20 people, 50 people, 100 people, 200 people. And so now I’m a big believer in like, you can’t overinvest in alignment and alignment is not just communication. And this is a muscle that I don’t think people in Silicon Valley exercise enough, is being very clear with team members of like: “Look, this is what we’re doing. If you’re excited about that, awesome. If you’re not, this might not be the place for you.” That is kind of strong language, but I have found it to be very powerful language because otherwise, people are just trying to pull it in all sorts of different directions.

– Thank you. And just to, like, double down on that last few statements: As your business grew, what were your main culture objectives, and how did you maintain or create that company culture? Did you have any hiring strategies or professional development plans that you leaned into? Tell us more about that.

– Yeah, no, it’s a good, I segued well into your next question. My early days, like, my first job out of college was at Oracle. I was a product manager there and I got very cynical, very fast. I was like this big company, I’m just sitting in meetings all day, well, anyway, I don’t want to name, well, there’s some fun stories there, but my manager at the time had some views about the efficiency and how it could be improved at the organization.

But that made me, like, there was a time where I said, “Khan Academy is always going to have, is always going to be a startup. It’s going to be a perpetual startup. I don’t want it to ever be a large company because large companies become bureaucratic and people just sit in meetings all day.” And so I had a view of “Let me just hire the smartest people I can and get out of their way and have as few meetings as possible.” That can sometimes be good, but it leads to issues at some point. Smart people, if they’re not aligned, can easily try to pull in different directions. And if you’re not communicating enough, you’re not going to get enough alignment. So over time, I’ve started to realize that it’s very important to, that we are a place where people can bring their full selves to. And because look, you’re spending a large chunk of your life doing work. And so, I try to—Khan Academy is a place where you shouldn’t be embarrassed to say that you’re going to take an hour to go meditate. You should be proud of that. You should even say that as an example. And look, a lot of that comes from me setting an example. It’s one thing to say it. It’s another thing to say, “Hey, I can’t attend that meeting because I’m going to be meditating,” and that sends a signal to other people. “Or I can’t do that evening meeting because I said that I’m going to do this event with my family that night.” So I think it’s very important to put those guardrails and all of that.

But I think culturally what I take a lot of, what I try to put a lot of energy into is making sure people are aligned. Like, disagreeing is great. Like, let’s disagree while we’re talking about the tactics of something, but we’ve got to make a decision and then we’ve got to commit to that decision, otherwise we’re just never going to go anywhere. And if you can’t truly commit to the decision and then that goes into the, like, this might not be the right place, right? Like, otherwise, you’re just going to be constantly trying to undermine it in passive-aggressive ways. So I think that’s another cultural thing.

I’ll say another cultural thing that I’ll say, which is, I think, obviously words like DEIB or letters like DEIB are, like, a big deal these days and they always have, and I’ve always been a very big believer in that. But I do believe that sometimes it is viewed as a signal for you are a left-leaning organization, or you say DEIB, but you really mean that you subscribe to these ideas that other people might not subscribe to, which is almost the opposite of DEIB, right? The whole argument behind diversity is that when you have different viewpoints, people who are different than you, now reasonable, and people who aren’t trying to shut each other down, et cetera. But if you have different reasonable viewpoints, that’s going to get your eventual decision to be a better place and people with very different experiences. And I remember a wake-up call for me was we had a senior executive at Khan Academy, this was about five or six years ago, and it was at an offsite, and all of a sudden, and he was an older gentleman and he said, “I was afraid to say this, but now I feel comfortable with y’all enough to say this. I’m an evangelical Christian and I’m a Republican.” And I remember when he said that, like half the team was like, “Wow, you’re so brave for saying that.” And then the other half of the team was saying things like, “Who did this guy vote for? And what’s his view on this and this?” And that was an eye-opener for me. It’s like, we can say DEIB, but we aren’t DEIB if that guy, who was really good at his job, who everyone really liked to work with, was afraid to even say what religion he is. And so what I try to do now is push everyone on DEIB where I say, “That’s not to hire more people that agree with you. That is to hire people who are truly from diverse perspectives that can push us to get to a better place.” So I think I take those words more seriously than a lot of other corporations that do it in a very performative way. I think there’s, most executives, if I’m honest, say I’m not going to get involved. I’m going to hire someone else to do that. And I’m just going to keep nodding and hope for the best versus actually trying to get true DEIB.

– Thank you for that. After hearing the inspiring story of the origin of Khan Academy, our ambitious and idealistic students here have questions for you. If you’re interested in asking a question, please go ahead and step to the mic right there in the aisle and tell us who you are and then go ahead with your question.

– Sal, thank you. Is this on? Probably not. OK, it is. Sal, thank you. My name is Doris. I’m a second year, and I lead our Haas Education Club here, which everyone should join. Aside from that pitch, oh, first off, I grew up hearing your videos, watching your videos, so I’m very familiar with that voice and today, I’m able to put that voice to the face and it’s great. My question for you is what is the largest gap that you see in American education today?

– Oh yeah, it’s a big one. I’ll say at least two. I’ll say the big one is, we fundamentally have a seat time based system, especially in high school, but even in college as well, right? In high school, we know the Carnegie units, which is like, you get a Carnegie unit when you sit in a year in math, a Carnegie unit, a year in English, et cetera. And even college, high school graduation requirements and college entrance requirements have stuff like you need to take three years of math. You need to take two years of foreign language. That, in no way, talks about whether you learn the math or learn the foreign language. So I would love to go more to an outcome-based or competency-based system that’s like, you should get to this level of math before graduating from high school. You should get to this level of reading, this level of writing. And if you don’t, you have the opportunity incentive to keep working on it. It’s not like it’s an all-or-nothing type of thing, but if you go there fast, great, you can get there fast and you can work on other things.

I think college should be the same, the fact that it’s all credit-hour based and that magically, regardless of what you major in, it’s all kind of like a four-year program. Yeah, there’s some arguments behind it from a stage of life point of view. So I would go to a competency-based, a corollary to that is being mastery-based, which is this idea that if students have a gap, a conceptual gap, that they have the opportunity, the incentive to continue to work on it. So if you’ve got a B in computer science, and two years later, you’ve mastered that material, you should be able to do something that allows you to show that you’re now at an A level, your transcript should be able to be upgraded, so to speak. And a correlator to that is, allow students to learn at their own time and pace.

– [Doris] Thank you.

– Hi, my name’s Patty Debenham. I run a center here for Haas students all about social impact. And I’ve been a big fan for a long time. I loved your book and at the end, you painted a terrific vision of a new kind of higher education that doesn’t cost $70,000 a year. I mean, even Berkeley, a public institution, is crazy expensive. I’d love to hear how you’re thinking about that now and how it can be possible that my 10-year-old doesn’t have to pay 70, well, I don’t have to pay $70,000?

– Yes. No, this is something I’ve been thinking a lot about and many of y’all know, I mean, I wrote that book, and then the year after I’m like, it’s one thing to write about a book. It’s a whole other thing to try to implement it. So I did start a school and now schools based on the principles in that book. We have Khan Lab school out down here in Mountain View and Palo Alto. And now there’s this Khan World school that we started with Arizona State University, which is a virtual high school. So the virtual middle and high school, and then Khan Lab school down here is K-12.

But the big question is: What about higher ed? And there’s a couple of tactics that we’re taking. One is we are actively exploring ways that Khan Academy, mastery on Khan Academy can result in college credit. So one method is if you can make essentially some version of dual enrollment via Khan Academy available to anyone on the planet, and it’s essentially it’s free or near free, and they can get a lot of these first- or second-year classes out of the way; that automatically lowers the cost of college education and actually increases the capacity for more people to get through the physical doors, so to speak. But the really cool thing would be if—and I don’t care if I’m involved—but someone, and there’s some universities, I think, that are already touching on that. There’s, like, Waterloo in Canada, which many of y’all know is an excellent, one of the world’s best engineering schools. Kids graduate from there, not with debt, but with savings because they use the co-op program so effectively, internships. And there’s another advantage where, while the Stanford and the Berkeley and the MIT kids are in classes in the fall and the spring, the Waterloo kids are getting, they get a monopoly in all the internships at all of the places, and they’re getting paid. And so that’s why not only are they getting better experience, they’re more employable. So I think a model like that would be really interesting. I would love to see it in the U.S. I know there’s a lot of talk these days about downtown San Francisco having emptied out. I’ve whispered to a few folks, “Hey, someone should start a university there, but make it so it’s free and not free through philanthropy.” Maybe you need some philanthropy to get it going, but in the long run, it’s free because the students are able to do a lot of real-world work that can be used to both pay the university and pay the students. So yeah, we’ll see. We’ll see. Yeah, your 10-year-old, I have about eight years to work on that. We’ll see what happens.

– Thanks for taking the time, Sal. My name is Asif. And a subject that talks about that learning to learn and critical thinking that you mention a lot is philosophy and looking at some of your books, maybe you’re a fan as well, but academic philosophy is famously dull, whereas the practical impacts of a philosophy educated population society is invaluable. So I’d love to get your thoughts on philosophy in the education system and maybe if you’re incorporating it into Khan World School or Labs.

– Yeah, so we definitely incorporate, like, when I think about what a great education looks like, I think you definitely should have Socratic dialogue about things like philosophy. I mean, there’s other types of things that you can get into really good, thoughtful debates and discussions about, but philosophy’s definitely like half of all the discussions that you could easily have. And at Khan World School, Socratic seminar is actually the anchor point for the whole school. And we’ve partnered with Steve Levitt’s group at the University of Chicago to create a whole list of topics. And half of them are literally philosophical, but they’re real-world philosophical to make it not just abstract. So there’s, like, literally a debate for middle school and high school students on things like should we leverage CRISPR to modify the human genome? Go. And all sorts of philosophical debates start to emerge from that. Will AI be a net positive or negative for humanity? Is GDP the best way to measure progress? You have to learn economics and history and math, but there’s a lot of philosophy in that. So yes, I’m a big fan of it. We’re definitely trying to, implementing the schools we’re doing.

The AI that we just, Khanmigo, which we built, we partnered with OpenAI over the last year. We launched with GPT-4 several months ago. One of the things that you can get into debates with the AI about frankly all of these topics and more, so that’s one way to hopefully scale it out a little bit more. And then we do have some content already on, and this is more academic philosophy. We’ve partnered with an organization, so that content is on Khan Academy. But yeah, I definitely think it is important. It is one of those things that I think you could have it in almost any subject. And I think that’s actually probably the way to make it, you tie it to real-world issues that is happening every day on the news. Like, reasonable people aren’t getting into debates about these things. Those are great fodder for philosophy.

– [Asif] Thank you.

– Hi, first off, a huge thank you. I was a public school teacher in New York City and Khan Academy liberated my classroom to be a standard space, like collaborative problem-solving space.

– [Sal] Oh, that’s good to hear. That’s the dream.

– My students in Brownsboro were, like, outperforming Westchester white, like, rich students because of work like yours.

– [Sal] If you have any information, I’m always looking of, anyway, but yeah, go.

– I’m looking for an internship this summer. But people looked at, and what made Khan different from me is that you trusted me as an educator to understand data and you gave it to me so I could use it. And you trusted my students to have the data too. That was better than ST, better than I learned, better than anything else. But people looked at me as an educator as unique because I knew how to use the data. My big fear going into AI and ChatGPT is how do we support and build a teacher force that is able to use that technology to liberate their classrooms?

– Yeah, that’s a great question. And what I’m hopeful about, obviously, it’s still very early days, we’re building this right now with all of our Khanmigo stuff. We realize it’s great; Khanmigo can act as a tutor, but it’s even more powerful that it can act as a teaching assistant. And some of that is to help with things like lesson plans and rubrics and give a first-pass grade and writing progress reports, which as you know, as a former teacher, take up a lot of your time.

– [Audience Member] A lot of time.

– So that’s good. But I also think that generative AI means the end of these, like, kind of spreadsheet looking dashboards that you’re familiar with because now it’s like you’re having an analyst. And we already have implemented some aspects of this where a teacher, instead of seeing the dashboard, right, and then having not every teacher can do what you did. And like looking at the dashboard and figuring out which kids could use what, they can just talk to the AI and say, “Hey, so what’s going on?” And the AI can say, “Well, for the most part, the students are doing all right. Here’s five kids who are, for the most part, struggling with these three concepts. Here’s an idea for a mini lesson that you could do with these three kids while the other, or these five kids while the other 20 or 25 students work at their own. Or if I were to group, or here’s an idea for a lesson, and by the way, I would group the kids this way for this reason. This third of the class is really struggling, this third is OK, this third is ready for some really enrichment. They’re getting bored. Let’s give them something else.” This isn’t science fiction anymore. And then if you want the data and the AI will say, “Oh, and by the way, if you don’t believe me, click here for the spreadsheet.” But I think that’s going to make it much more accessible to all teachers. You’re going to be able to text with the dashboard, so to speak, and say, “What should I do? What insights are here? What do you recommend I do next with the students?”

– [Audience Member] Thank you.

– Hey, Sal, my name’s Alex. Following up on that a little bit on the Khan World Academy, I was listening to the podcast with Steve Levitt, and initially I was skeptical, but then I heard the student talking about her experience and it started making a lot more sense. And so I was more curious if you can go in on, like, how you continue to design that curriculum and also what your vision is to scale that up so that more students can have an experience like that?

– Yeah, I mean the beauty of Khan World School and ASU, we did it ’cause ASU already runs ASU prep, which already has 40,000 students, so they know how to scale. And they already have a charter in the state of Arizona, which means ASU prep. And now Khan World School is free to any student in the state of Arizona. And hopefully, we can get charters in other states as well. So that free, world-class education for anyone, anywhere can be true beyond Arizona ’cause this is a full school.

A lot of the principles are what we’ve learned over 10 years running the physical Khan Lab School. And also what I wrote 10, 11 years ago in The One World Schoolhouse, students learning at their own pace, having more agency autonomy, the adults, the teachers, the guides, whatever you want to call them, their time focused more on unblocking students, motivating students, advising students, driving Socratic seminars versus lecture, et cetera, et cetera. And with a virtual environment, you’re not bound by time or space in the same way. And we also wanted to show that you could do virtual much better than people did it in the pandemic where it was soul-crushing. And so, we anchor it with a Socratic dialogue. Kids get an hour or two of synchronous community-building discussion advisory every day, but then they have a lot of autonomy to do other things.

And to your point, Steve Levitt, who everyone knows here from Freakonomics, famous economist, he’s not a sucker for bad data. But as far as we can tell, these kids are not learning 20, 30% faster. They’re learning two x, three x faster, and they’re enjoying it. And there’s stuff we’re not even measuring like the seminar ’cause there aren’t any standardized tests for how good someone is at seminar. But we feel confident that these are well-rounded students that are going to really thrive later on.

– [Alex] Thank you.

– Thanks, Sal. My name is Vinit, and I’m in the MBA program. So recently, I started getting excited and passionate about using technology and AI to perhaps achieve, like, educational parity. And so I was at this San Francisco tech meetup, and I started going around and just started pitching this idea to some folks. Look, we don’t need to teach children or kids how to use computers or even learn how to code anymore. Like, AI can generate code. We need to just provide them more creative ways to play with code or sort of just give them, like, the fundamental building blocks like Legos using AI and they can just sort of create apps on their own and feel empowered about themselves. And what ended up happening throughout the course of the evening was when I talked to the investor community, like the VCs and folks, they would just look at me like, no, no, like EdTech’s a very, very difficult business model. You’re either going to have to sell to the parents or schools, which is no joke. And then there happened to be folks there that were parents and many of them were technologists famously creating apps for adults. But then when it comes to their own kids, they would say like, “No, I just want my kids to play outside, be in the nature. Like, I personally believe that technology hasn’t really given us anything meaningful in form of, yeah, education other than Khan Academy, of course.” But I mean, it is valid concern giving tha the rates of stress, anxiety and focus attention for teenagers or preteens especially has gone up quite a lot recently. So, yeah. I don’t really have a question. I guess I would wonder how I really want to remain optimistic, and you’re one of the few people that I see that are optimistic still in this space. So when you’re not speaking to a room of full of people that have already bought into this idea, I guess, how do you convince those folks, whether it’s parents or investors or whoever it is?

– Yeah, well, I think a bunch of stuff you said resonates with, I think the VCs you’re talking to are right. EDTech is a hard thing especially if you’re trying to get VC-like returns. It’s a very hard thing. And if you want to get VC-like returns, you probably will have to sacrifice some of, maybe some of your principles around like, OK, let’s make this a thing for rich kids, and maybe it helps them cheat a little bit or something like that. Honestly, there are multi-billion dollar publicly traded EDTech companies, that is their business model. I won’t name names. So it is hard ’cause it’s, and it’s even harder if you’re trying to introduce a new paradigm around, in your case, engineering/coding.

My answer to the screen time is, it’s not about screen time is neutral. There’s some very good uses of screen time. Obviously, if a student is writing a paper, coding, doing some graphical art, I argue Khan Academy. But even that needs to be within reason. For my own children, I still want them to go outside, play with their friends. If someone visits Khan World School or especially Khan Lab School, if they visit, you’re going to see kids not on a computer all day. They do probably use a computer more than your average school, but they’re also getting more social interaction than your average school because they’re not sitting in lectures all day, either. So Khan Lab school kids are constantly working on projects and collaborating and walking around the space. They don’t have to sit in one chair all day. So I’m a big believer in that. So my advice would be, you might be trying to tackle too many degrees away from where people’s comfort zone is right now, but maybe there’s a way to take that same tool and show that you could use it to create, like, enterprise apps or things like that, and college students could use it to start companies. That could probably get, I could imagine, VCs wanting that even to start their own incubator. They create an app like that, and people could come in and just write apps really, really, really fast and get product market fit tests really, really fast. That could be an interesting model.

But maybe there’s other things if you find the right partner with Lego or something, I don’t know, it’s not easy to pull off. Who knows? I don’t want to discourage you either ’cause what I was doing in 2008 or 2009, people found far, far more ridiculous than what you are doing. So people thought not-for-profit, YouTube videos, personalized learning, all of these stuff, was sounded ridiculous.

– [Vinit] Thank you.

– Well sadly, we are out of time. Thank you for the time that you’ve spent with us today, Sal.

– [Sal] Thanks for having me.

– Thanks to our moderators, Anu and Mrudula. Thanks to all of you for joining us. This has been a wonderful and inspiring hour. I hope you’ll join us again for future Dean Speaker Series. Have a wonderful day.

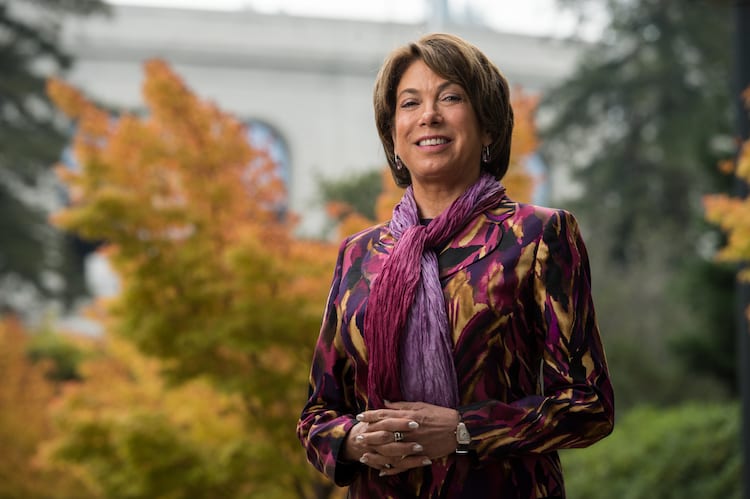

Berkeley Haas Dean Ann Harrison grew up with an insatiable curiosity and a dream to make the world a better place.

Berkeley Haas Dean Ann Harrison grew up with an insatiable curiosity and a dream to make the world a better place.

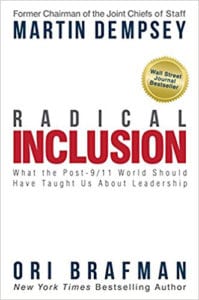

As an undergrad at Berkeley, Ori Brafman had been many things—a peace and conflict studies major, anti-war protestor, and vegan activist whose McVegan campaign had taken on McDonald’s and won. The last place he thought he’d find himself a decade later was in the office of a 4-star army general. “At the time, I had no idea what a 4-star general was,” admits Brafman, BA 97, a Berkeley Haas lecturer who teaches improvisational leadership in the MBA and undergraduate programs. “My first question was, ‘Is there a 5-star general?’”

As an undergrad at Berkeley, Ori Brafman had been many things—a peace and conflict studies major, anti-war protestor, and vegan activist whose McVegan campaign had taken on McDonald’s and won. The last place he thought he’d find himself a decade later was in the office of a 4-star army general. “At the time, I had no idea what a 4-star general was,” admits Brafman, BA 97, a Berkeley Haas lecturer who teaches improvisational leadership in the MBA and undergraduate programs. “My first question was, ‘Is there a 5-star general?’”

National Energy Finance CompetitionA special

National Energy Finance CompetitionA special

Over the next few years, as the cultural conversation around women at work gathered momentum, companies started asking McElhaney for more proof of a bottom-line payoff to hiring women.

Over the next few years, as the cultural conversation around women at work gathered momentum, companies started asking McElhaney for more proof of a bottom-line payoff to hiring women.